by Robert Fay

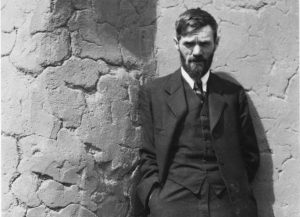

D.H. Lawrence had the goods on America. Like many foreign intellectuals and artists before and after, he was interested in the American “spirit of place” and its people’s curious experiment with displacement. He knew the “old American classics” stood toe-to-toe with the great Russian and French masterpieces of the 19th Century, but he also knew there were a lot of bodies buried out back, and understanding America started from there.

In his masterful Studies in Classic American Literature (1923) he wrote, “at present the demon of the place and the unappeased ghosts of the dead Indians act with the unconscious and under-conscious soul of the white American, causing the great American grouch, the Orestes-like frenzy of restlessness of the Yankee soul, the inner-malaise that almost amounts to madness, sometimes.”

Lawrence was writing here about James Fenimore Cooper’s novels and the countries’ shameful relations with Native Americans, but it could equally apply to America’s ongoing treatment of African Americans. Lawrence goes on to observe, “America is tense with latent violence and resistance. The very common sense of white Americans has a tinge of helplessness in it.”

There’s a growing consciousness among (some) white Americans that racism is not simply a societal ill creeping toward extinction (“Look, we just had a black president!), but more like a malarial parasite that cleverly adapts itself to new circumstances, new opportunities.

Books like Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow (2011) remind us racism isn’t a feeling or a point-of-view, but a systematic and institutional approach to shackling black people. She writes, “since the nation’s founding, African Americans repeatedly have been controlled through institutions such as slavery and Jim Crow, which appear to die, but then are reborn in a new form, tailored to the needs and constraints of the time.” Alexander argues that the mass incarceration of black Americans since the 1970s—done under the auspices of “the war on drugs”—is the current method of controlling and disenfranchising large segments of the black population. Same game, different name.

*

Well-meaning white Americans, particularly those in publishing, the academic fields, the arts, education, etc., are trying to buck up and examine their own culpability in America’s original sin. This is encouraging at a time when the President of the United States refuses to formally denounce neo-Nazi activity but, as with all moral crusades, there is always the danger of overreach, where progressive zeal can spill over into zealotry. A recent essay by Angela Pelster-Wiebe in Literary Hub titled, “White Artists Need to Start Addressing White Supremacy in Their Work,” illustrates how wrestling with one’s own heart can foster a curious form of proselytization.

The headline in Pelster-Wiebe’s piece is somewhat misleading, because she is not arguing that all white artists should address racism, but she is calling out those artists who have decided to address white supremacy and are failing at the task. She cites a number of efforts, including the 2017 movie Detroit by director Kathryn Bigelow and Anders Carlson-Wee’s poem “How To,” concluding, “white artists often fail at this work because they haven’t centered themselves within the violence of their own whiteness.” Aside from the rather esoteric challenge of centering oneself, there is no doubt white Americans have been slinking away from the country’s ugly history for centuries now, and Mr. Lawrence would likely nod his head in agreement.

Yet the truly interesting part of Pelster-Wiebe’s piece is that its arguments rest on two entirely unquestioned assumptions about art. The first is that artists have a responsibility to society to “say something” about the ills of the day, and secondly, Pelster-Wiebe clearly believes that art has a morally uplifting effect on humanity, otherwise, why bother persuading anyone “to do good.”

She writes, “When white art that is meant to address (emphasis added) white supremacy fails…” and then, positing the moral argument, “the increasing social fear of white writers and artists at the possibility of getting this wrong and causing harm when they intended to good (emphasis added).”

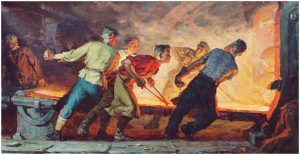

It’s my hope that all artists spare us their good intentions. Go read the biographies of your favorite painters, novelists and composers, and you could be forgiven for concluding artistic success might actually hinge on immorality. The Social Realist artists in the Soviet Union were certainly intending to do good—as interpreted by the Communist Party of the U.S.S.R—but I sure as hell don’t want their paintings on my walls. Ayn Rand wanted to do good (read: she had an agenda) and then there were writers like George Orwell and André Malraux with their unabashed political affinities. Today we get more than enough advocacy from the so-called creative class. Each day I turn to my phone and feel like I’m drowning in Twitter ads, political speech, marketing campaigns, algorithmically-manipulated Facebook stories—everyone and everything has a point-of-view.

Art, however, isn’t about answers. Artists aren’t sure-footed beat reporters, but spelunkers who are unaccustomed to the light of day. David Shields in his book Reality Hunger (2010) helps get at what art and artists “do”:

“The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. Art exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony.”

I love this idea of “perception” versus what is “known.” On a certain level, art is about the individual experience of being alive. Reading Marcel Proust is such a thrilling experience, not because I’m gathering social data about Belle Époque France, but simply because the particular human consciousness identified as Monsieur Proust is so sublime, nuanced, perceptive, foreign, and in visiting his imagination, I find myself more alive than ever, despite his complete indifference to my moral state.

I suspect that even a genius like Proust could not have overcome Pelster-Wiebe’s starting point: “Let’s see. I wish to address the issue of anti-Semitism in France, and as such, I shall develop a seven-volume series that artfully explores the social attitudes towards the Dreyfus Affair via a cast of curious Parisian aristocrats.”

And I know Pelster-Wiebe appreciates this. She realizes what a drag it must be for non-white writers who are expected to self-consciously—and explicitly—write about being black, Asian, Latino, etc. She notes, “Artists and writers of color are often expected to live out some kind of eternal recurrence on a theme of only addressing racism in their work when the entire universe of ideas is at their feet, same as any other writer.”

But somehow Pelster-Wiebe feels that white artists need to take up this burden. I admire her compassionate, socially-responsible worldview. This is what we need in state legislators, school teachers, physicians, parents, CEOs, community activists, the people who have an explicitly responsibility to be custodians of a decent and fair society. But I hope Pelster-Wiebe’s own artistic work remains wild, unfettered, uncomfortable, even surprising to herself.

The artist has no responsibility to anyone, but herself. Artists and writers may be the last truly free persons in our society. The human imagination is not a social policy platform. History teaches us that even in the worst situations, in concentration camps, famines, wars, natural disasters, the human imagination can transcend the horrors of its physical environment.

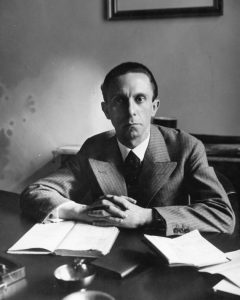

And speaking of horrors, the NAZI leadership offers a classic example of how art and literature do not make us good people. Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda of Nazi Germany was a literary fellow. He studied literature at the university, aspired to be a writer, and he wrote his doctoral thesis on a 19th century German romantic playwright. Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring was a great collector (and looter) of art, who loved Renoir, Rubens, Monet, Corot, van Gogh, Botticelli, and many others. Hitler’s beloved architect Albert Speer was also brilliant and sophisticated man, so let’s not pretend art makes us more empathetic.

*

Lawrence wrote his book on American literature in the 1920s at a time when sympathy for aboriginal peoples or sensitives about minorities had little-to-no vogue. Lawrence knew that James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking novels had nothing to do with “reality,” with the actual history of white pioneers and Native Americans. But they are good reads, interesting imaginative inventions. “The Leatherstocking books are lovely. Lovely half-lies,” Lawrence wrote. “They form a sort of American Odyssey, with Natty Bumpo as Odysseus.” He continues with this vein, writing about Cooper’s novel Deerslayer, “…It is a myth, not a realistic tale. Read it as a lovely myth.”

Vladimir Nabokov put it this way, “Literature is invention. Fiction is fiction. To call a story a true story is an insult to both art and truth. Every great writer is a great deceiver…”

I think we all have a good idea who can (or at least should) get to work on promoting social progress and racial injustice in this country, but it sure as hell isn’t artists. They are first-class liars whose precious resources are locked far underground. And getting to the goods requires deep water drilling and fracking, with all the attendant filth and environmental degradation. No one emerges with clean hands in the process, but all same, we all need the oil.

Pelster-Wiebe and other good-meaning people want to make artists propogandists for a good cause. Those of us living in artsy, comfy blue-state cities or who have teaching gigs at universities, sometimes have trouble understanding that telling people what to do (or not do) can seem quite illiberal. The African-American writer Roxane Gay believes white writers should not even try to use African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) in their work. “Don’t use AAVE. Don’t even try it,” she said. “Know your lane.” Gay even applies this rule to herself, because she didn’t grow up in environment where AAVE was spoken. With all due respect to Gay, writers need to write what they write. Their job is to create elaborate fairy tales, not to be documentarians of their own (often) unremarkable upbringing (I hope I’m not restricted to writing only about Irish-Catholics from Boston). Let’s remember Franz Kafka wrote about the United States in Amerika, though he’d never visited the country. Was he wrong to do so?

It’s certainly true that violating the fashionable rules of the day might mean you never get published, but so be it, you can always self-publish. Proust did it. So can you.

In the end, let’s give artists the room to surprise us—perhaps even disappoint us. It’s their job to perceive as Shields put it, and reflect back to us.

“The old American artists were hopeless liars,” Lawrence reminds us. “But they were artists in spite of themselves. Which is more than you can say of most living practioners.”

Robert Fay’s essays, reviews and stories have appeared in The Atlantic, The Millions, The Los Angeles Review of Books and The Chicago Quarterly Review, among others. Follow him on Twitter @RobertFay1.