by Eric J. Weiner

From Saint Pélagie Prison in 1883, Paul Lafargue wrote The Right to Be Lazy, an anti-capitalist polemic that challenged the hegemony of the “right to work” discourse. The focus of his outrage was the liberal elite as well as the proletarians. His central argument is summed up in this quote:

Capitalist ethics, a pitiful parody on Christian ethics, strikes with its anathema the flesh of the laborer; its ideal is to reduce the producer to the smallest number of needs, to suppress his joys and his passions and to condemn him to play the part of a machine turning out work without respite and without thanks.

Quite a bit has changed since he wrote his polemic, yet I think there are some important insights that still resonate in the 21st century. Unlike the industrialism that informed Lafargue’s critique of the bourgeoisie’s work fetish, time at work in the 21st century is no longer primarily experienced in the factory or small brick-and-mortar business. In today’s knowledge economy, we celebrate a form of “uber” work where workers “enjoy” the flexible benefits of constant connectivity, borderless geographies of work/time, and schedules unconstrained by days-of-week or time-of-day. Workdays blend into work-nights which slide into work-mornings without beginning or end. Not unlike techniques of “enhanced interrogation” that leverage the power of time to (dis)orient, in our current historical juncture time is erased leaving workers without a sense of place; there is nothing to distinguish Wednesday from Sunday, Monday from Friday. In this new timeless workscape, the old adage TGIF is meaningless, an artifact as quaint as the vinyl record or paper road maps. Within this environment, workers struggle to adapt to this new model. For example, people still claim to need more time, yet in the 21st century postmodern workscape, time no longer has a meaningful referent. It simply floats above labor signaling neither a beginning nor end. Clocks likewise have become a quaint, antiquated technology of a mechanical era, yet they are still ubiquitous in most work-spaces. In this new workscape, clocks don’t measure time in order to determine the value of one’s labor on an hourly, weekly, or annual calendar. For uber-workers, the clock never gets punched because it doesn’t really exist in the context of their flexible workscapes. At most, they can orient workers to meet up for lunch or for that rare occasion when a body-to-body meeting is desired (it rarely is). They also, in the form of a wrist watch, can represent a kind of retro-cool, a form of cultural capital, especially when the watch is an “automatic”!

Uber workers are “free” to take a break yet no one can or actually does because “taking a break” requires one to be at work somewhere, anywhere. Today’s uber-workforce has no indigenous location, no point of reference in time and space and therefore no recognizable beginning or end. Without this geography of labor, workers are always “on,” and never “off.” This constant state of work is then described as a form of freedom. Read more »

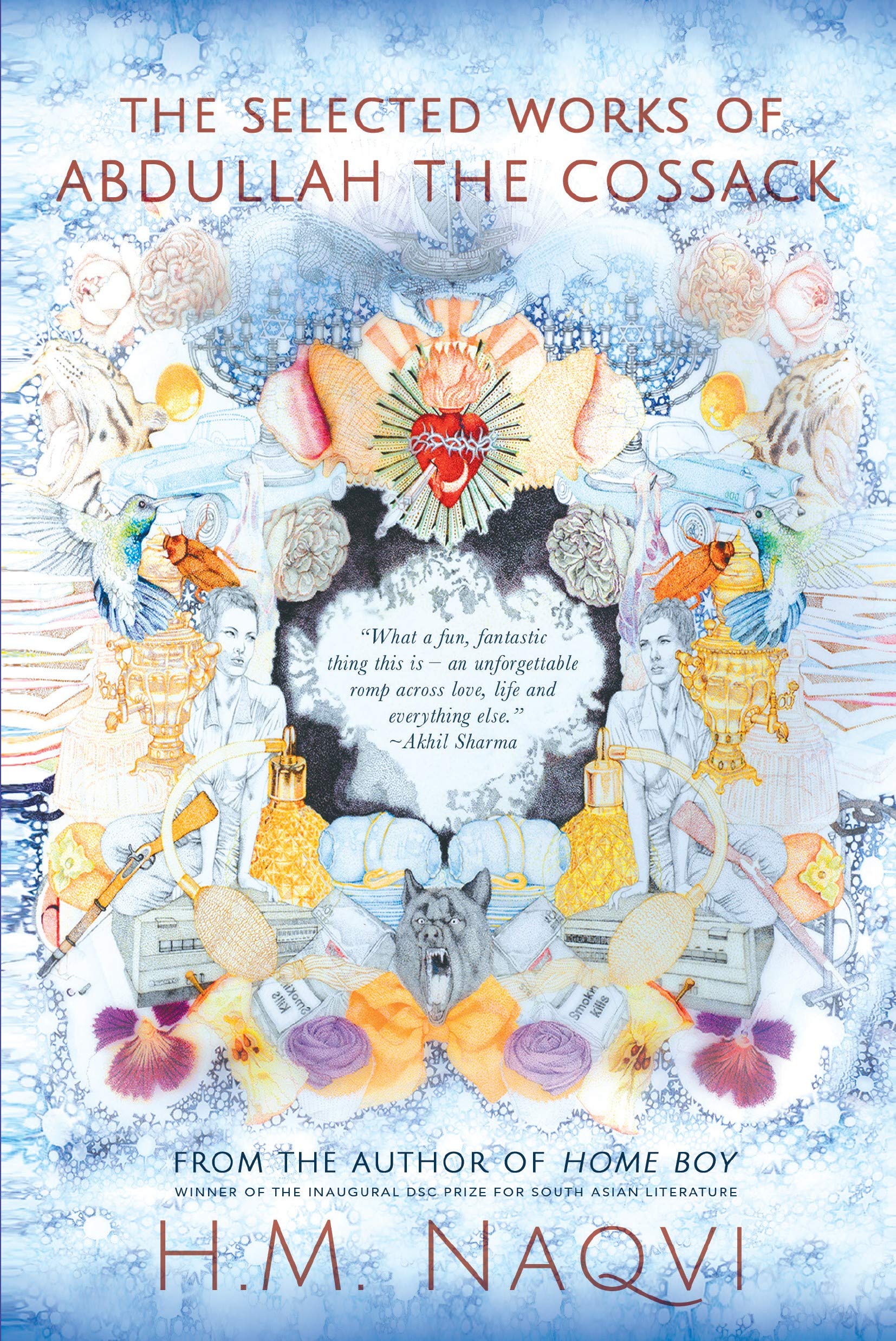

Early in H.M. Naqvi’s new novel The Selected Works of Abdullah the Cossack (SWAC from here on out) we come across this exchange between Abdullah and a devout young Pathan as the former, in poor health and out of breath, is seen taking a drink of water from a thermos on a sweltering day during the holy month of Ramzan when most able bodied and observant Muslims choose to fast between sunrise and sunset.

Early in H.M. Naqvi’s new novel The Selected Works of Abdullah the Cossack (SWAC from here on out) we come across this exchange between Abdullah and a devout young Pathan as the former, in poor health and out of breath, is seen taking a drink of water from a thermos on a sweltering day during the holy month of Ramzan when most able bodied and observant Muslims choose to fast between sunrise and sunset.

The right to own guns is typically justified by the fundamental right to self-defense against bad guys, either our fellow citizens or the state itself if it were to turn tyrannical. Both of these have a superficial appeal but fail in obvious ways. Guns are an effective means of defending oneself against bad guys only so long as they don’t have guns too (because being equally armed doesn’t add up a defense against those who can pick and choose their moment of aggression). Civilians with guns are also ineffective against the armies and ruthless terroristic violence of a truly tyrannical regime.

The right to own guns is typically justified by the fundamental right to self-defense against bad guys, either our fellow citizens or the state itself if it were to turn tyrannical. Both of these have a superficial appeal but fail in obvious ways. Guns are an effective means of defending oneself against bad guys only so long as they don’t have guns too (because being equally armed doesn’t add up a defense against those who can pick and choose their moment of aggression). Civilians with guns are also ineffective against the armies and ruthless terroristic violence of a truly tyrannical regime. So goes a popular snippet from Seinfeld. In a 2014 article in The Guardian titled “Smug: The most toxic insult of them all?” Mark Hooper opined that “there can be few more damning labels in modern Britain than ‘smug.'” And CBS journalist Will Rahn declared, in the wake of Donald Trump’s 2016 electoral victory, that “modern journalism’s great moral and intellectual failing [is] its unbearable smugness.”

So goes a popular snippet from Seinfeld. In a 2014 article in The Guardian titled “Smug: The most toxic insult of them all?” Mark Hooper opined that “there can be few more damning labels in modern Britain than ‘smug.'” And CBS journalist Will Rahn declared, in the wake of Donald Trump’s 2016 electoral victory, that “modern journalism’s great moral and intellectual failing [is] its unbearable smugness.”

I was perhaps ten years old when I had unending cups of Eatmore’s fresh handmade mango ice cream while sitting on the lawns of Services Club Sialkot. It was one of the brightest days of my life, with my parents all to myself, undistracted by the demands of their daily doings, and the crystal cups of ice cream brought to us. We sat on reclining garden chairs on the perfectly manicured lawn, bordered by fragrant

I was perhaps ten years old when I had unending cups of Eatmore’s fresh handmade mango ice cream while sitting on the lawns of Services Club Sialkot. It was one of the brightest days of my life, with my parents all to myself, undistracted by the demands of their daily doings, and the crystal cups of ice cream brought to us. We sat on reclining garden chairs on the perfectly manicured lawn, bordered by fragrant

If a rectangular canvas splashed with paint and lines can express freedom or joy, why not liquid poetry?

If a rectangular canvas splashed with paint and lines can express freedom or joy, why not liquid poetry?

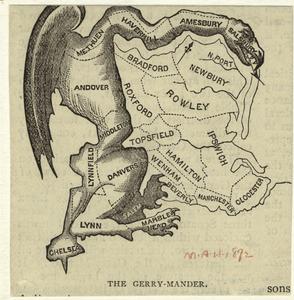

The Supreme Court doesn’t play politics.

The Supreme Court doesn’t play politics.