by Eric J. Weiner

Border culture is a project of ‘redefinition’ that conceives of the border not only as the limits of two countries, but also as a cardinal intersection of many realities. In this sense, the border is not an abyss that will have to save us from threatening otherness, but a place where the so-called otherness yields, becomes us, and therefore comprehensible–Guillermo Gomez-Peña, 1986

La cultura fronteriza es un proyecto de “redefinición” que concibe la frontera no sólo como los límites de dos países, sino también como una intersección cardinal de muchas realidades. En este sentido, la frontera no es un abismo que deba salvarnos de la otredad amenazante, sino un lugar en el que la llamada otredad cede, se convierte en nosotros y, por tanto, es comprensible–Guillermo Gómez-Peña, 1986

Nelson Mandela, in a speech inaugurating the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund, said, “There can be no keener revelation of a society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children.” Echoing his words, the authors of UNICEF’s Child Poverty Report write, “The true measure of a nation’s standing is how well it attends to its children – their health and safety, their material security, their education and socialization, and their sense of being loved, valued, and included in the families and societies into which they are born.” As people in the U.S. and throughout the world bear witness to other people’s children languishing in overcrowded facilities along the southern border of the United States, I think a more keener revelation of a nation’s soul and a measure of its standing is how well it treats other people’s children—their health and safety, their material security, their education and socialization, and their sense of being loved and valued.

Nelson Mandela, in a speech inaugurating the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund, said, “There can be no keener revelation of a society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children.” Echoing his words, the authors of UNICEF’s Child Poverty Report write, “The true measure of a nation’s standing is how well it attends to its children – their health and safety, their material security, their education and socialization, and their sense of being loved, valued, and included in the families and societies into which they are born.” As people in the U.S. and throughout the world bear witness to other people’s children languishing in overcrowded facilities along the southern border of the United States, I think a more keener revelation of a nation’s soul and a measure of its standing is how well it treats other people’s children—their health and safety, their material security, their education and socialization, and their sense of being loved and valued.

Nelson Mandela, en un discurso de inauguración del Fondo Nelson Mandela para la Infancia dijo: “No puede haber una revelación más aguda del alma de una sociedad que la forma en que trata a sus niños”. Haciéndose eco de sus palabras, los autores del Informe sobre la Pobreza Infantil de UNICEF escriben: “La verdadera medida del prestigio de una nación es lo bien que atiende a sus niños: su salud y seguridad, su seguridad material, su educación y socialización, y su sensación de ser amados, valorados e incluidos en las familias y sociedades en las que nacen”. Mientras la gente en Estados Unidos y en todo el mundo es testigo de cómo los niños de otras personas languidecen en instalaciones superpobladas a lo largo de la frontera sur de Estados Unidos, creo que una revelación más aguda del alma de una nación y una medida de su posición es lo bien que trata a los niños de otras personas: su salud y seguridad, su seguridad material, su educación y socialización, y su sentido de ser amados y valorados. Read more »

Two weeks ago European soccer world was rocked by an announcement that 12 of the top clubs had agreed among themselves to form a European Super League (ESL) to replace the existing European Champions League (ECL). The “dirty dozen” were Real Madrid, Barcelona, Atletico Madrid, Juventus, Inter Milan, AC Milan, Manchester United, Manchester City, Liverpool, Arsenal, Chelsea, and Tottenham. These teams were to be joined by another 8, bringing the total up to 20. A defining feature of the ESL would be that 15 of its members would be guaranteed their place in the competition no matter how they performed the previous year or in their domestic competitions.

Two weeks ago European soccer world was rocked by an announcement that 12 of the top clubs had agreed among themselves to form a European Super League (ESL) to replace the existing European Champions League (ECL). The “dirty dozen” were Real Madrid, Barcelona, Atletico Madrid, Juventus, Inter Milan, AC Milan, Manchester United, Manchester City, Liverpool, Arsenal, Chelsea, and Tottenham. These teams were to be joined by another 8, bringing the total up to 20. A defining feature of the ESL would be that 15 of its members would be guaranteed their place in the competition no matter how they performed the previous year or in their domestic competitions.

All of human life is quite literally coded into two long, complementary strands of genetic material that fold themselves into a double helix. When cells divide, copies of this genetic code must be made – a process that is known as replication. The double helix unwinds, and a “replication fork” makes its way down the helix in much the same way that a slider separates the teeth of a zipper. Once separated, enzymes get to work on replicating them. Except, only one of the strands is replicated continuously. The second strand is replicated piecewise first, and these pieces – called Okazaki fragments – are then fused together.

All of human life is quite literally coded into two long, complementary strands of genetic material that fold themselves into a double helix. When cells divide, copies of this genetic code must be made – a process that is known as replication. The double helix unwinds, and a “replication fork” makes its way down the helix in much the same way that a slider separates the teeth of a zipper. Once separated, enzymes get to work on replicating them. Except, only one of the strands is replicated continuously. The second strand is replicated piecewise first, and these pieces – called Okazaki fragments – are then fused together. Hassan Abbas’s book, “The Prophet’s Heir: The Life of Ali ibn Abi Talib,” provides an excellent basis for much research, reflection and conversations.

Hassan Abbas’s book, “The Prophet’s Heir: The Life of Ali ibn Abi Talib,” provides an excellent basis for much research, reflection and conversations.

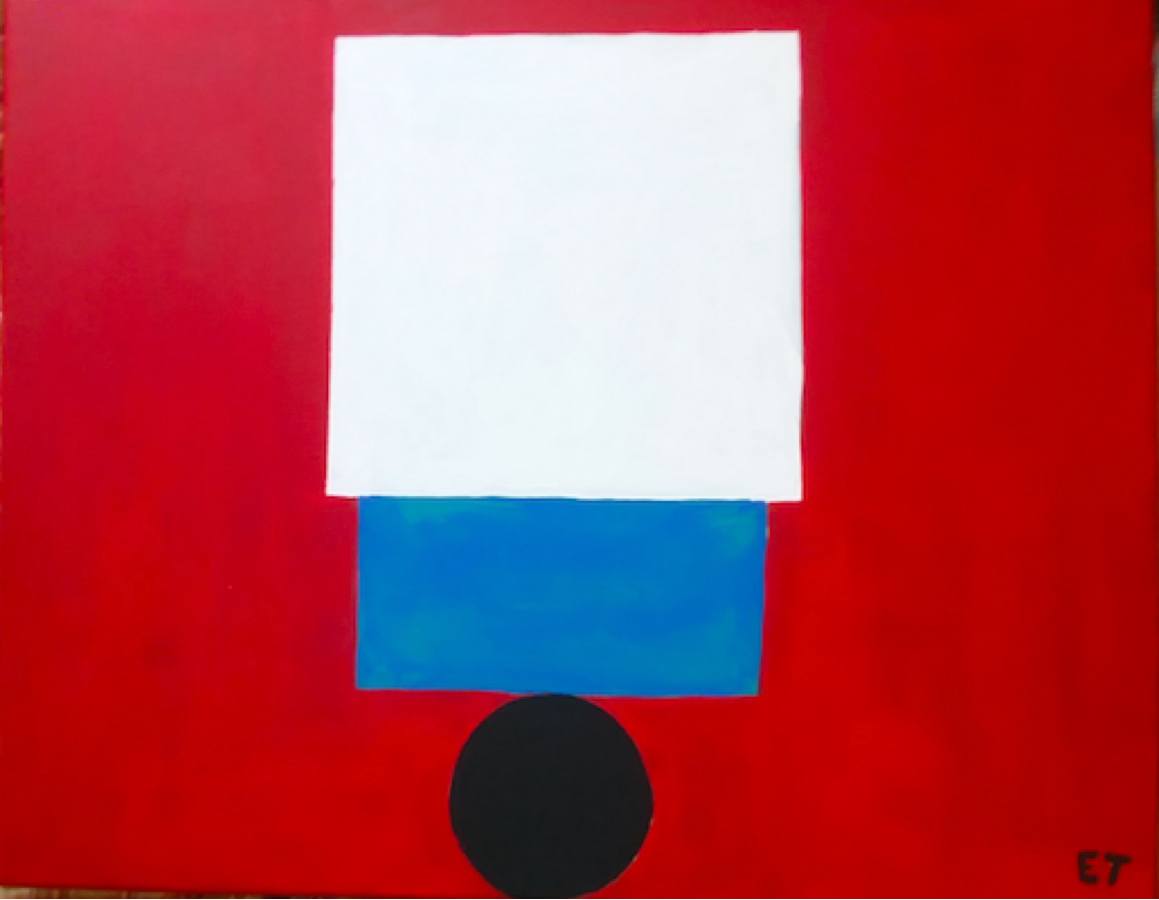

ET Trigg. I Can’t Breathe, 2020.

ET Trigg. I Can’t Breathe, 2020. “Why, during the seventeenth century, did people who knew all the arguments that there is a God stop finding God’s reality intuitively obvious?” This, says Alec Ryrie in his Unbelievers: An Emotional History of Doubt (2019), is the heart of the question of early modern unbelief (136).

“Why, during the seventeenth century, did people who knew all the arguments that there is a God stop finding God’s reality intuitively obvious?” This, says Alec Ryrie in his Unbelievers: An Emotional History of Doubt (2019), is the heart of the question of early modern unbelief (136). On Saturday, April 10, 2021, in Fribourg in the west of Switzerland, Besuch der Lieder, the troupe of musicians with whom

On Saturday, April 10, 2021, in Fribourg in the west of Switzerland, Besuch der Lieder, the troupe of musicians with whom

They call it the Sargasso, this grass. It is the bane of Belize, an invasive floating weed that keeps pitchforks flailing along the waterfront. The Sargasso Sea, we know where that is. But this grass is from Brazil, Réné says. It’s a new challenge from a new place. It isn’t challenge enough just to weather a pandemic, he says. Now there’s this, too.

They call it the Sargasso, this grass. It is the bane of Belize, an invasive floating weed that keeps pitchforks flailing along the waterfront. The Sargasso Sea, we know where that is. But this grass is from Brazil, Réné says. It’s a new challenge from a new place. It isn’t challenge enough just to weather a pandemic, he says. Now there’s this, too.

That is, we had to talk about it. I thought of a musician as someone who made a living performing music. I didn’t do that. To be sure, I made some money playing around town in a rock band and I’d spent years learning the trumpet. I’d marched in parades and at football games; I’d played concerts with various groups. But I wasn’t a full-time, you know, a professional musician, a real musician. Gren insisted that I was a musician because I played music, a lot, and was committed to it. That’s all that’s necessary.

That is, we had to talk about it. I thought of a musician as someone who made a living performing music. I didn’t do that. To be sure, I made some money playing around town in a rock band and I’d spent years learning the trumpet. I’d marched in parades and at football games; I’d played concerts with various groups. But I wasn’t a full-time, you know, a professional musician, a real musician. Gren insisted that I was a musician because I played music, a lot, and was committed to it. That’s all that’s necessary. Podcast time!

Podcast time!