by Eric J. Weiner

Now I saw his lifeless state. And that there was no longer any difference between what once had been my father and the table he was lying on, or the floor on which the table stood, or the wall socket beneath the window, or the cable running to the lamp beside him…And death, which I have always regarded as the greatest dimension of life, dark, compelling, was no more than a pipe that springs a leak, a branch that cracks in the wind, a jacket that slips off a clothes hanger and falls to the floor. ―Karl Ove Knausgård, Min kamp 1

After two days of celebrating my 40th birthday in Atlantic City, I barely could put two words together. I slumped over my sunny-side up eggs in the Continental diner across the parking lot from the Dunes motel. Battered from salty air and indifference, it was the perfect place to crash when you knew you wouldn’t be getting much sleep. The year was 2007 and the end of history was bleeding into tomorrow like a hemophiliac walking across a field of broken glass.

I poked my fork into one of the yolks and watched it slowly creep across my plate toward the enormous pile of canned corned beef hash. I gratefully sipped the hot, black coffee while choking down a slice of buttered rye toast. Paul, one of my oldest friends, sat across from me, stoned and chill, staring into the white and silver-speckled formica tabletop, looking for answers to questions only he knew. I rarely smoked weed, but his state of placid contentment was a good argument to start smoking more. The sound of eggs, green peppers, melted cheddar, and onions mashing and churning in his cottony mouth made me shiver with nausea and want to kill him with my butter knife. I ground the base of my hands into my eye-sockets trying in vain to quiet the hive of hornets that tore through my brain. My heart hammered against the back of my chest and even though the diner was ice-cold, I was sweating like a mule. My clothes still smelled of smoke, gin and Paco Rabanne cologne. My bloodstained eyes betrayed my desire for more of everything.

The morning after a man crawls from the wreckage of his lost youth, naked and alone in the sanctimonious light of civilized society, he reeks of nostalgia; a stench so repugnant and pathetic that even my shopworn waitress–sexy-as-hell in her short, pale-yellow uniform that hinted at a tattooed vine of skulls and thorny black roses around her inner-thigh–was moved to sympathy. Topping-off my coffee comforted me like last rites to the dying faithful. There ya go, darling, she whispered as she slithered away to bless another patron with her consecrated pot of coffee. What a great ass, I thought as I watched her take pity on a sweaty, fat man in a Hawaiian shirt and cowboy boots. What I really needed was a Xanax with a spicy, bloody mary chaser. But I knew where that would lead and I desperately wanted to return home.

My razr flip-phone rang, jerking me out of my stupor; diners glared at me from their half-eaten plates of breakfast gruel. Grabbing for the phone, I spilled half my coffee onto my lap and the other half across the table onto Paul. He barely stopped chewing. What a second ago was a comforting, steamy sacrament was now scalding my thighs and staining my pants so it looked like I pissed myself. The lord wasn’t mysterious, I thought, just fucking vengeful. I jumped up from my seat swearing loudly. I didn’t recognize the number on the phone, but I answered it anyway. Before I could unleash my rage, the man on the phone quickly told me that he was on the side of route 940 in the Poconos and that my father and his wife, Ruth, had been in a motorcycle accident. I started to involuntarily shake as I walked out of the diner to continue the call. My voice trembled as I asked some questions that would assure me the whole thing wasn’t some kind of sick joke. You never know. People can be fucked-up. Once convinced, I asked him if my father was alive. He said he was. Ruth was not seriously hurt, he volunteered. The paramedics at the scene were going to take my father to a trauma center in Scranton. I hung up and called my wife, Cat, who was also in the AC area, and we started the tense, four-hour drive to Scranton.

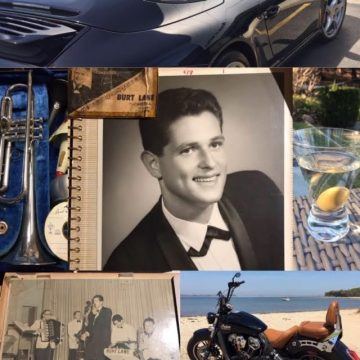

As we were driving through Philadelphia, where my father lived his whole life before retiring to Lake Naomi in upstate Pennsylvania in 2005, I finally and luckily reached someone in the trauma center. The nurse told me that he would be transported by helicopter to Thomas Jefferson Hospital’s trauma unit in Philadelphia. The injuries he sustained, I was told, would be better treated at Jefferson. She wouldn’t tell me on the phone anything specific about his injuries, only that he’d need a lot of rehab but he’d be fine. I knew Jefferson hospital well as it was where my father, years earlier, was treated for mouth cancer. The oncologist removed a section of his tongue and several slivers of gum. As a pro-level trumpet player, this was devastating. My father never played the trumpet again, switching instead to electric, jazz guitar. Music, gin martinis, fast and expensive German sports cars, smoking, skiing, and riding his motorcycle were the six things of which he was ever really passionate. When he quit drinking and smoking, could no longer afford the cars, and could no longer ski due to shattering his femur in seventeen places in a freak accident at Camelback ski mountain, his world became painfully cramped and, I believe, relentlessly boring. Ruth, who was on the back of the bike when it collided with the spooked deer, was his faithful companion and tough as a bag of bricks.

They met in a bar twenty-seven years prior to the accident and had been married for seventeen of them. When they met, she was a single, twenty-seven-year-old, math teacher at Olney High School, my father’s alma mater. Tall, slender, mid-western, and Nordic, she was the perfect clichéd complement to my father; a handsome, paunchy, married and bored Jewish, narcissistic forty-year-old Philadelphian with a black, 911 Targa, stainless steel Rolex Submariner on his wrist, two demanding (spoiled) kids at home, and a serious taste for Tanqueray martinis, up, very dry, with a twist. Only Philip Roth, or maybe Woody Allen, could have come up with a more desperately comic set-up. She was getting a ride down from Scranton with the man who had called me from the highway. Both would meet us at Jefferson.

While we waited for my father to arrive, Cat and I ate some pub food and had a bloody mary or two to help ease the stress and quiet those relentless hornets. Even though my father and I were not close, I was genuinely relieved that he would recover from whatever injuries he had sustained. I hoped he and I would ride motorcycles together again; it was one of the only things we could do together without it devolving into some kind of disagreement, which then would morph into a spirited argument, until, inevitably, it would become a no-holds-barred ad hominem fight from which we wouldn’t talk for months. He walked out on the family just shy of my 13th birthday and our relationship never recovered. I was constantly pissed-off and he was sick of me being constantly pissed-off. Fair enough. But we didn’t see each other often and we both were okay with that.

Upon check-in at the front desk of the hospital, we were quickly lead down a dark, back corridor to a row of empty elevators. On our way up, I turned to Cat in the silent car, my legs getting weak, and whispered, Serious enough for you, yet? Exiting the elevator, we were told to have a seat in the small waiting room. A surgeon in blue scrubs wearing a little surgical beanie quickly came and sat down across from us. He told me that my father had suffered a “catastrophic brain injury.” He was brain-dead. He was being kept “alive” on a ventilator, but was, for all ways that I think matter, dead. Was he wearing a helmet? he asked. Yes, he was, I answered, even though I wasn’t sure why it mattered to know such a thing. If he wasn’t, would I then have had to hear from the surgeon about the preventable tragedies he sees every day if only cyclists would wear their helmets? The surgeon explained how the left side of my father’s brain was damaged beyond repair in spite of the helmet and, as a consequence, he would not have any capacity for language. Because of my education in linguistics and literacy, I had some basic idea as to the seriousness of this kind of injury; without the capacity for language, if he survived, he would be in a persistent vegetative state for the rest of his days. He would, however, be able to breath on his own. The surgeon told us that if my father had smashed the right side of his head against the asphalt instead of the left he could probably have recovered and lead a relatively normal life. Fifty-fifty chance. Could have gone either way. Shit luck, Dad. The doctor could “save” him with surgery. But he wanted to know what I wanted him to do. If they didn’t do the surgery in the next twenty minutes, he would be permanently on life-support or die. He stared at me, waiting.

I stared back. Cat cried. I could feel panic and fear, like a thousand razorblades slowly cutting deeper and deeper into my flesh, start to overtake my ability to concentrate. They told me he was okay, I said. Who said? he asked. Scranton, the nurse in Scranton; the guy who called me from the road; everyone said he would be okay! No, I’m sorry, he replied matter-of-factly, that was not true. I stared at him. He offered that if it was his father he would not do the surgery. If I had to guess, I would say we were about the same age. I was grateful for his perspective and honest counsel. I called Ruth who was still driving down from Scranton. I told her what the surgeon had said. She knew my father better than I did. He didn’t have a living-will and they apparently never discussed this scenario. She agreed that he would not want to live in a vegetative state for the rest of his life. He was only sixty-seven-years-old and could survive for many years. Maybe she didn’t want him living in a vegetative state; she was only fifty-four-years-old. We elected not to do the surgery. I walked out into the hallway and crumpled to the floor, violently grabbing my hair and screaming into my knees. A nurse sat down on the floor beside me. He was kept on a ventilator until my sister could fly in from the west coast. Once we took him off life-support, his heart kept beating for another three days.

Although my father wasn’t a violent man and meant well, we were estranged. His involvement in my life for the twenty-seven-years between the time he left my mother (and me and my sister) and the motorcycle crash, was minimal yet filled with hostility, guilt, absence, and textbook narcissism; but it was also peppered with some truly good and memorable times. He taught me how to ride a motorcycle, ski, drink, listen to jazz, appreciate German engineering, drive fast, and meet women. We did these things to varying degrees together yet always emotionally apart. As I got older, we saw each other a few times a year. Sometimes we would get together for a motorcycle ride through the mountains and I would watch with pity, frustration, and anger as he aged and weakened; his evolving fragility frightened as much as it disgusted me. He struggled to handle the huge Harley but refused to trade it in for something smaller and lighter. Ironically, the bike he was riding when he died was the one that he finally did get that was smaller than his big tour bike. He bought it days before his fatal accident. The bike was totaled in the crash; it was a beautiful, black, Heritage Springer Soft Tail with black leather saddlebags. Just gorgeous. The photograph that the dealership’s salesman took of him on his new bike at the time he picked it up concealed his personal demons. No one knew about the compulsive spending habit and one-hundred thousand dollar revolving credit card debt that he carried and struggled to pay. My father was a handsome man and always looked confident and happy when riding and playing music. Put a martini glass and cigarette in his hand, seat him behind the wheel of a BMW or Porsche, get him on-stage blowing his horn, and he seemed unstoppable. Only after his death, did I start to understand how much of his life was overshadowed by the constant specters of failure, disappointment, and insecurity.

Estranged from his biological father who abandoned the family for a younger and blonder woman when he was thirteen-years-old, my father grew-up an only-child under the authority of a violent step-father. He was a shady Philadelphia mounted cop who ran numbers out of the basement of their row house at “D and the Boulevard.” He physically hurt Anne, my grandmother, and terrorized my father. I still remember the denseness of the worn, leather “blackjack” he always carried in his back pocket. One smack to the base of the skull, he would tell me during our annual Thanksgiving dinner, would quickly put a large man down like a sack of potatoes. My father was a “bag boy” in his youth (delivering bets and money to gamblers and the bookies working the phones in the basement), the first in his family to go to college, and a working musician with his own band called the Burt Lane Orchestra (Lane being a better show name than Weiner).

He once told me about a time the FBI raided his row house, apparently tipped off about the illegal gambling operation going on in the basement. When he came home from school, his house was swarming with federal agents. The men who were working the phones in the basement were sitting on the floor in hand-cuffs. His mother was in hand-cuffs, too. He told the agents who he was and asked if he could go to his room. The officer gave him permission but told him to come back out as soon as he had put his things away. Entering his room, he opened his closet to hang up his jacket only to find a man hiding inside. What did you do? I asked, amazed and impressed. I handed him my jacket, he said with a smile, shut the closet door, went back to the living room, and sat quietly until the FBI left the house. My father was trained to be a real estate appraiser (eventually became a real estate developer), married my mother, gave up his dream of becoming a full-time professional musician and band leader, and quickly moved to Willow Grove, a suburb about fifteen miles north of Philadelphia, to start a family.

He was not a violent man, “a lover not a fighter,” he would proudly tell me with a mischievous grin. My father, like all the other fathers in my circle of friends, were, to varying degrees, sexist. Women were first assessed for their looks and then their sexuality. Women were sliced up into pieces; legs, eyes, ass, breasts, lips, hair, etc. Each body part would be evaluated for its imagined sexual potency. The women these men found desirable were always much younger than themselves. It’s not that these men didn’t also value strong, confident, and intelligent women; they just weren’t the first things they saw or about which they would comment. I also had several friends whose fathers were, in addition to being overtly sexist, quite violent as well. From wrenches thrown at small heads that barely ducked out of the way before impact to sustained injuries serious enough to keep one of them out of school for a week or more, most of the fathers in my world were far from the idealized versions that I saw on the television shows Happy Days, The Brady Bunch, and The Cosby Show. The fathers I knew, especially in comparison to the mothers, were violent or celebrated violence, tended to be emotionally absent, were consumed with activities that took them away from family (i.e., work, hobbies, sports), and tediously sexist. Few of these men equated rewriting the patriarchal script of masculinity with being a good father. I learned from these men what it meant to be a man, even as I rebelled against their one-dimensional representation of fatherhood.

Times change, but it is still hard for many men, myself included, to imagine what it means to be a father–good or bad–without the patriarchal script as a guide. This is a problem beyond the definition and practice of fatherhood; it gets at the heart of what it means to be a man within our patriarchal system. Many men believe if they teach their sons to follow the patriarchal script then they are being good fathers. But if we don’t rewrite what it means to be a good father, aren’t we then bound to reproduce models of masculinity that are patriarchal? If so, our sons get trapped in a one-dimensional paradigm of male identity and our daughters get stuck having to fight against the willful ignorance of one-dimensional men. In the name of my father, a man who I now believe did the best he could with what he had, I hope I can, for my daughter, do better.

This is my struggle.