Sughra Raza. Untitled, April 2021.

Sughra Raza. Untitled, April 2021.

Digital photograph.

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

Sughra Raza. Untitled, April 2021.

Sughra Raza. Untitled, April 2021.

Digital photograph.

by Thomas O’Dwyer

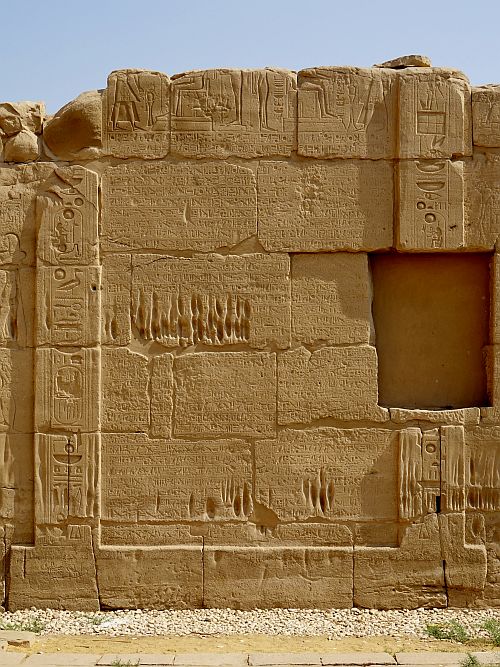

Complicated international agreements on managing the planet’s many human and natural resources may seem essentially modern, a consequence of the interdependence between nations that has been growing since the 19th century. Such accords are as necessary as sewage pipes that underpin healthy societies and just as boring. However, we possess copies of the first known international agreement signed in human affairs — and it is 3,300 years old. This treaty for peace and economic cooperation ended conflicts between the Egyptian and Hittite empires. Archaeologists found a copy of the treaty from each side, one in Egyptian hieroglyphics in 1828 and the other in Hittite cuneiform text in 1908. The treaty itself, signed by Pharaoh Ramses II and King Hattusilis, became a model of endurance in the fractious Middle East of the 13th century BCE (plus ça change). The formerly warring states remained friends and allies for nearly 100 years until Assyria invaded and destroyed the Hittite kingdom.

And now we move from possibly the first international agreement in human history to maybe the last — if it doesn’t work, and fast. In November, Scotland will host the most prominent international conference ever seen in Britain, a memorable event with an eminently forgettable title, the 26th Conference of the Parties — COP26. (The United Nations is well known for the tedium of its terminology). A conference of the parties is the supreme governing body of any international convention and includes representatives of all the states involved plus any observers. In UN-speak, a COP aims “to review the implementation of the convention and any other legal instruments that the COP adopts.” The COP descending on Glasgow in six months has the task of saving humanity, no less, for it has to advance the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. Most will have been unaware that this conference of the parties has met (almost) every year since the first in 1995 in Berlin. The “parties” are 197 states and territories that signed on to the Climate Change Convention. And what, you may well ask, have these vast gatherings of blathering heads achieved since 1995? The answer, in good British slang, would be “Bugger all!” Read more »

by Mark Harvey

Three years ago while filling my truck with gas in western New Mexico on a cold fall evening, a young woman, barefoot and wearing nothing but a sundress, came up to me and asked if she could get a ride into the town of Gallup. Her bare feet and summer clothing in the biting air made me suspicious so I asked her a few questions. She told me she was traveling home to Taos after spending some time in the Pacific Northwest and that she had no money and had been hitchhiking for days. She was a little disheveled, startlingly beautiful, and her story didn’t make much sense. But she looked cold so I agreed to take her to Gallup, thinking I might be of some small help.

We got in my truck and started down the highway when she said, “Do you mind if we go back and get my boots?”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“My boots, I left them on the road a little before the gas station.”

So we turned around and drove back a few hundred yards and sure enough, there was a pair of pink cowboy boots neatly placed on the side of the road. At that point—as if the signs weren’t strong enough already–I realized the woman might be suffering some psychological trauma and that her thinking was foggy. I asked her if she had some family to call in Taos, but she said she couldn’t get in touch with them.

I had just been shopping for groceries and the woman asked if she could have something to eat. I told her to eat anything she wanted from the bag. She devoured a bag of almonds and a couple of apples as if she hadn’t eaten for days. As we approached Gallup, I asked her again if there was someone she could call for help. She said there was no one and that she would be fine. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Andrea Scrima

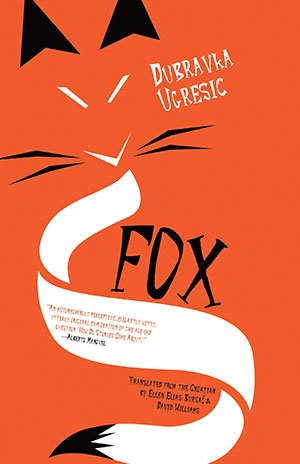

“If the spirit of the fox enters a person, then that person’s tribe is accursed.”

1.

In his 1953 essay “The Hedgehog and the Fox,” which postulates two quintessential moral dispositions at the heart of history’s main opposing ideologies, Isaiah Berlin divides the world’s influential writers into two categories of thought. Elaborating on Berlin’s dichotomy in her latest book Fox, which came out the spring of 2018 in English translation, Dubravka Ugrešić distinguishes between “those who write, engage, and think with recourse to a single idea (hedgehogs), and those who merge manifold heterogeneous experiences and ideas (foxes).” Clearly, the fox sounds more enticing; Berlin equates the hedgehog with authoritarianism and totalitarianism, while the fox is deemed liberal and tolerant. The only problem is the questionable reputation it’s earned among the world’s oldest mythologies, fairytales, and legends: whatever it might have going for it in the way of “pluralistic moral values,” the fox has long been accused of “cunning, betrayal, wile, sycophancy, deceit, mendacity, hypocrisy, duplicity, selfishness, sneakiness, arrogance, avarice, corruption, carnality, vindictiveness, and reclusiveness.” That’s quite an indictment—and all the more reason for Ugrešić to select the wily animal as patron saint of her new book.

Fox is subtle, virtuosic, and jarring; it’s also mordantly funny. In light-footed, deceptively playful detours and digressions, the book skips from Stalinist Russia to an American road trip with the Nabokovs, academic conferences and literary festivals to the largely untold story of the Far-East diaspora of persecuted Russian intellectuals on the eve of World War II. Fox is a novel, but its formal structure poses a challenge; some chapters read as essays, some as autonomous short stories, and while many recurrent threads reveal themselves upon closer inspection and reflection, it requires attention to unravel the author’s narrative strategy. Read more »

by Fabio Tollon

Elon Musk. Either you love him or you love to hate him. He is glorified by some as a demi-god who will lead humanity to the stars (because if it’s one thing we need is more planets to plunder) and vilified by others as a Silicon Valley hack who is as hypocritical as he is wealthy (very). When one is confronted by such contradictory and binary views the natural intuition is to take a step back and assess the available evidence. Usually this leads to a more nuanced understanding of the subject matter, often resulting in a less binary, and somewhat more coherent narrative. Usually.

The idea to write something about Musk was the result of the reality bending adventure that was Edward Niedermeyer’s Ludicrous: The Unvarnished Story of Tesla Motors.

Let us take a look at the basics. Musk is a Silicon Valley entrepreneur who made a fortune by helping to found PayPal. Using the capital gained from this venture, he invested $30 million into Tesla Motors, and became chairmen of its board of directors in 2004. He also eventually ousted the founders of the company Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning. He is currently CEO of Tesla, Inc. (the name was officially changed from Tesla Motors to Tesla in 2017) and is in regular competition with human rights champion Jeff Bezos for the glamorous title of “world’s most successful hoarder of capital”. I don’t want to spend too much time on the psychology of Elon Musk, as Nathan Robinson has already done a fine job in this regard. Rather, I want to focus on how Tesla is not the market disrupting company many think it is. Here I will be concerned with the mismatch between Silicon Valley’s software driven innovation versus the kind of innovation that exists in the auto industry. Read more »

Son, I Again Dreamt About You Last Night

A version after Iqbal

I couldn’t find the road in the dark,

my every hair bristled

but I dared myself and walked on,

saw boys swaying in single file,

each holding a Diya lamp in his hand,

their clothes glowed like emeralds—

God only knew where they were going. . .

I saw you at the end of the line,

your Diya unlit. “Heartbeat of my heart,”

I said, “where are you going after abandoning

me? All day I thread my tears into a necklace.

“Don’t weep for me,” you said, “don’t yearn

for me there is no gain in it for me —”

then you fell silent for a moment

looked at your Diya again, and spoke

“Mother,

do you know what happened? Your tears

of sorrow dowsed it.”

***

By Rafiq Kathwari. His new collection of poems “My Mother’s Scribe” (Yoda Press) is available here and here.

by Philip Graham

I am a writer, not a musician. I play no instrument, and I confine my singing to the car when driving alone. Yet my momentary career as a musical performer—exceedingly brief as it may have been—enjoyed a spotlight rarely offered to others.

car when driving alone. Yet my momentary career as a musical performer—exceedingly brief as it may have been—enjoyed a spotlight rarely offered to others.

Public acclaim is simply the last step in a long fraught journey. Many years ago a friend, whose first novel had begun climbing the bestseller lists, privately complained to me that book reviewers and journalists had dubbed her an “overnight success.” As she rightly pointed out, there is nothing “overnight” about writing a novel.

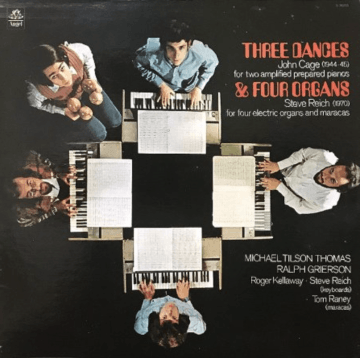

My unlikely musical debut was the end result of a long and circuitous path, a path that closely tracked with my love of minimalist music. While there are many possible ways to tell this story, a good place to start would be my days as an eager undergraduate, and my attendance at an early performance of Steve Reich’s Four Organs at New York’s Shakespeare Public Theater in the fall of 1971. Read more »

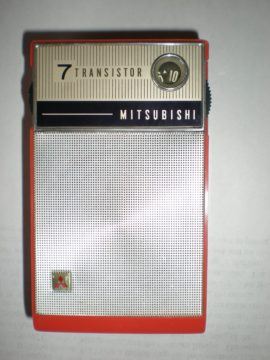

by Carol A Westbrook

In the summer of 1961, my dad gave me a little transistor radio. My older sister, Lynn, showed me how to tune it to WLS and WCFL, the stations that played music that all the teens listened to. They had the best Chicago DJ’s: Dick Biondi and Larry Lujack, who wise-cracked and took calls. And she showed me how to listen to it under the pillow at night. (Click on the song names to listen to the music.)

One night I heard a song, “The Mountains High” that stuck with me all my life. As a top 40s hit, it was played a lot, until its ratings fell and it disappeared from the air. It’s about a couple who are separated by an impassible mountain. “Don’t you give up, don’t you cry, don’t you give up ‘till you reach the other side…” they sang. This song captured all the angst of a preteen, longing for travel, adventure, and especially love. And love was so unattainable to a 7th grade girl, for the simple reason that the 7th grade boys didn’t care much about girls–yet.

That was the summer of 1961. I was about to enter 7th grade, and I was growing up fast. I was no longer “just a kid down the block.” I was a young woman. My brother threw me off his sandlot baseball team because they had a “no dames” policy, and they finally noticed I was a girl. But I didn’t mind; I had other things to do. I hung with my girlfriends. We talked about boys. We read teen magazines to see the latest styles. We tried on makeup and new hairstyles. We had pajama parties, where we stayed up all night, listening to the top 40 hits on late-night radio. We watched American Bandstand, where a few lucky teenagers got to be on television, dancing to the latest songs played by Dick Clark, the DJ. There was always a popular band playing their top hit, too. How we envied those kids! We paid careful attention to their clothes, hair and their dancing, trying to emulate it. Read more »

by Jochen Szangolies

Meet Hubert. For going on ten years now, Hubert has shared a living space with my wife and me. He’s a generally cheerful fellow, optimistic to a fault, occasionally prone to a little mischief; in fact, my wife, upon seeing the picture, remarked that he looked inordinately well-behaved. He’s fond of chocolate and watching TV, which may be the reason why his chief dwelling place is our couch, where most of the TV-watching and chocolate-eating transpires. He also likes to dance, is curious, but sometimes gets overwhelmed by his own enthusiasm.

Of course, you might want to object: Hubert is neither of these things. He doesn’t genuinely like anything, he doesn’t have any desire for chocolate, he can’t dance, much less enjoy doing so. Hubert, indeed, is afflicted by a grave handicap: he isn’t real. He can only like what I claim he likes; he only dances if I (or my wife) animate him; he can’t really eat chocolate, or watch TV. But Hubert is an intrepid, indomitable spirit: he won’t let such a minor setback as his own non-existence stop him from having a good time.

And indeed, the matter, once considered, is not necessarily that simple. Hubert’s beliefs and desires are not my beliefs and desires: I don’t always like the same shows, and I’m not much for dancing (although I confess we’re well-aligned in our fondness of chocolate). The question is, then, whom these beliefs and desires belong to. Are they pretend-beliefs, beliefs falsely attributed? Are they beliefs without a believer? Or, for a more radical option, does the existence of these beliefs imply the existence of some entity holding them? Read more »

by Martin Butler

Shoshona Zuboff’s “The age of Surveillance Capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of Power” gives an impressive and comprehensive account of how the big tech companies gained their economic dominance, and why this is a problem.[1] We hear much about how these companies fail to pay their fair share of taxes, how they have become monopolies, and how they enable online abuse.[2] Zuboff’s concerns, however, are with a less obvious problem but one that is perhaps more insidious.

The main companies she has in mind are Google and Facebook, although the methods they have discovered are, she claims, spreading throughout the capitalist economy and giving rise to a new form of capitalism altogether, which she identifies as surveillance capitalism. This, she argues, is something so different from anything we have experienced before that we are completely unprepared to deal with it, and it has arisen so quickly and come to dominate so much about our lives that we are still like rabbits caught in the head-lights. Zuboff reminds us of a pivotal truth, easily forgotten, that despite the disingenuously user-friendly message they assiduously promote, these two companies are in essence platforms for advertising and this more than anything else determines what they do. Read more »

At twenty I danced the tops of walls

Najinsky of the double top plate

bent in-two like an onion shoot

unbending up through an earthen gate

lifting sticks to be put in place

nailing their tails held against my boot

walking the wires of gravity’s net

as a spider commands the filament web

hung in the crotch of the jamb of a door

between one post and its lintel head

From the crow’s nest of my wall-top perch

poised to get the next piece set

in air as clear as a baby’s thoughts

surveying homes unlived-in yet

fresh-footed, balanced, without a clue

assessing my recent work and worth:

the shadows of studs plumb and true

lying like bars over up-turned earth

Sweatskin slickkening in the light

breath as sure as the bellows of god

biceps built by the truth of weight,

muscles doing their natural jobs:

arms of sinew, bone and grit

reaching to haul the next board up

to be lifted and laid wall to ridge

and fixed by hammer blows on steel

fueled by blasts of the burning bush

in the orchard of god that has ever spun

like the fire that made big Moses reel

the burning bush we call the sun

Jim Culleny

2/22/13

by Godfrey Onime

Short and snappy, the smooth-faced lieutenant-colonel who had been appointed deputy inspector-general of hospitals for the British army would butt heads with non-other than the chaste, indefatigable Florence Nightingale. A heroine of Victorian England who was celebrated as the pioneer of nursing during the Crimean War, Nightingale wrote to her sister about their clash, “He behaved like a brute… the most hardened creature I have ever met.”

His name was Dr. James Miranda Barry. Obsessed with hygiene, when inspecting his troops he would bark, “Dirty beasts! Go and clean yourselves!” The standards of even ‘the lady of the lamp’ Nightingale were not high enough for Dr. Barry, and I can just imagine the differential Nightingale trying not to show her fuming as the doctor berated her in front of her subordinates. Unlikely as it may seem, this short-tempered “brute” turned out to be the champion of women, or more specifically, of pregnant woman – a reason that became more understandable only after his death. Read more »

by Joseph Shieber

Optimism about the miraculous speed with which researchers were able to develop and test extremely effective anti-Covid vaccines is beginning to sour as vaccination rates slow down. These slowing rates raise worries about whether the United States will be able fully to defeat Covid-19, since a full return to normalcy would require high levels of vaccine compliance — much higher levels than we’re currently witnessing.

The challenge, as I’ve pointed out before, is that pandemics force us to recognize that our behaviors have implications beyond our own lives. Without sufficient vaccine uptake, we won’t be able to return to work, school and leisure activities with the same maskless nonchalance with which we pursued them in 2019.

This fact gives the lie to the framing of the vaccine on some media sites, framing that suggests that vaccine deniers are simply exercising their “personal freedom” in choosing not to get vaccinated. In a very real sense, my freedoms — my freedom not to have to wear a mask when I lecture in the classroom, to be able to send my children to school in an environment in which they don’t have only 10 minutes in which to eat lunch … no talking allowed! — depend on others’ willingness to get vaccinated. Read more »

by Jackson Arn

To ease the days’ constipation, I tried exercise. At first I jogged, but jogging was less interesting than the park I was supposed to jog through. I did pushups. These also proved less interesting than I had hoped. Sit-ups were an okay compromise between ignoring my phone and giving it my full attention, but after a while, say fifteen minutes, giving would take revenge on ignoring and the days would be re-constipate themselves and my apartment would feel smaller than ever.

I was smart enough to recognize that the problem was me. When I was in middle school, the object of my earliest non-nocturnal boner inspired me to get my dad’s barbells out of the basement. This went on for maybe three days. Apart from that, I’d never exercised on purpose. My powers of concentration are too weak. They’re the kind that inspire long articles about why America is doomed and there’s nothing we can do. My mom used to play me jazz and opera. Neither took. So it followed that I couldn’t exercise until I had become a different kind of person, and since that seemed unlikely it also followed that I was unlikely to exercise much. I concluded this in between refreshing my Bitcoin page. If civilization goes boom I won’t be able to outrun my neighbors but at least I’ll be a billionaire.

A few days later, I realized there might be a loophole. I was checking my Bitcoins at the time, and the rectangle of my laptop filled with an almost-as-big rectangle. It was a pop-up for a workout class. The face of the class was a man called Dave, or a “man” called Dave, or a man called “Dave,” or a “man” “called” “Dave.” Dave, as I’ll call him, resembled a hard worker, but he never sweated. Whenever I got a look at his whole body it had that post-greenroom glibness, like it moved because some offstage somebody said so and not because Dave’s muscles clenched.

I didn’t go for the class since all my savings were tied up in cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, but the basic idea of the ad seemed correct to me. My concentration was weak, but even I could stand in my apartment and imitate someone else’s exercise, even if they weren’t really in my apartment. Read more »

by Alexander C. Kafka

A lyrical disaster movie? That sounds like a contradiction in terms, yet the Swedish collective Crazy Films delivered just that in 2018 with The Unthinkable, and it is arriving on American platforms this month.

The picture is a hybrid of Swedish family drama and low-budget but well-executed calamity, as though a late-career Ingmar Bergman decided to make a contemporary apocalyptic film with Roland Emmerich as an advisor. It’s toward the milder end of perpetual Hollywood bombast, which only makes it more effective because its moments of terror swoop in hawk-like and leave you dazed, just like the film’s protagonists.

Crazy Films is five guys who have been making movies together since they were kids. Their previous works were shorts on YouTube, so the sustained, polished handling of on-set, model, and CGI mayhem here is really remarkable, as is the existential subtext and the unapologetically dour nature of its hero. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Dwight Furrow

Wine and music pairing is becoming increasingly popular, and the effectiveness of using music to enhance a wine tasting experience has received substantial empirical confirmation. (I summarized this data and the aesthetic significance of wine and music pairing last month on this site.) But to my knowledge there is no guide to how one should go about wine and music pairing. Are there pairing rules similar to the rules for pairing food and wine? Is there expertise involved that requires practice and experience?

Wine and music pairing is becoming increasingly popular, and the effectiveness of using music to enhance a wine tasting experience has received substantial empirical confirmation. (I summarized this data and the aesthetic significance of wine and music pairing last month on this site.) But to my knowledge there is no guide to how one should go about wine and music pairing. Are there pairing rules similar to the rules for pairing food and wine? Is there expertise involved that requires practice and experience?

In fact, there are no rules for pairing food and wine. Every so-called rule is subject to so many exceptions, it is misleading to think of these guidelines as rules. Yes, white wine often goes well with seafood but not always, and there are some red wines that are enjoyable with seafood. The same is true when pairing music with wine. There are general guidelines with many exceptions. Thus, like food and wine pairing, experience is important, and some expertise can be helpful. Below I describe my own process for generating wine and music pairings and the generalizations that can be drawn from it. Read more »