by Mark Harvey

Three years ago while filling my truck with gas in western New Mexico on a cold fall evening, a young woman, barefoot and wearing nothing but a sundress, came up to me and asked if she could get a ride into the town of Gallup. Her bare feet and summer clothing in the biting air made me suspicious so I asked her a few questions. She told me she was traveling home to Taos after spending some time in the Pacific Northwest and that she had no money and had been hitchhiking for days. She was a little disheveled, startlingly beautiful, and her story didn’t make much sense. But she looked cold so I agreed to take her to Gallup, thinking I might be of some small help.

We got in my truck and started down the highway when she said, “Do you mind if we go back and get my boots?”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“My boots, I left them on the road a little before the gas station.”

So we turned around and drove back a few hundred yards and sure enough, there was a pair of pink cowboy boots neatly placed on the side of the road. At that point—as if the signs weren’t strong enough already–I realized the woman might be suffering some psychological trauma and that her thinking was foggy. I asked her if she had some family to call in Taos, but she said she couldn’t get in touch with them.

I had just been shopping for groceries and the woman asked if she could have something to eat. I told her to eat anything she wanted from the bag. She devoured a bag of almonds and a couple of apples as if she hadn’t eaten for days. As we approached Gallup, I asked her again if there was someone she could call for help. She said there was no one and that she would be fine. Read more »

car when driving alone. Yet my momentary career as a musical performer—exceedingly brief as it may have been—enjoyed a spotlight rarely offered to others.

car when driving alone. Yet my momentary career as a musical performer—exceedingly brief as it may have been—enjoyed a spotlight rarely offered to others.

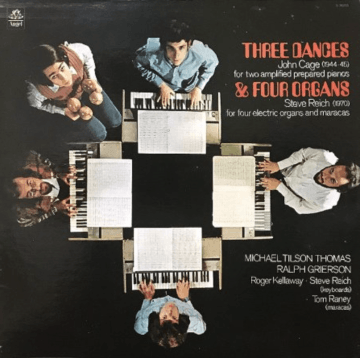

Wine and music pairing is becoming increasingly popular, and the effectiveness of using music to enhance a wine tasting experience has received substantial empirical confirmation. (I summarized this data and the aesthetic significance of wine and music pairing

Wine and music pairing is becoming increasingly popular, and the effectiveness of using music to enhance a wine tasting experience has received substantial empirical confirmation. (I summarized this data and the aesthetic significance of wine and music pairing  Two weeks ago European soccer world was rocked by an announcement that 12 of the top clubs had agreed among themselves to form a European Super League (ESL) to replace the existing European Champions League (ECL). The “dirty dozen” were Real Madrid, Barcelona, Atletico Madrid, Juventus, Inter Milan, AC Milan, Manchester United, Manchester City, Liverpool, Arsenal, Chelsea, and Tottenham. These teams were to be joined by another 8, bringing the total up to 20. A defining feature of the ESL would be that 15 of its members would be guaranteed their place in the competition no matter how they performed the previous year or in their domestic competitions.

Two weeks ago European soccer world was rocked by an announcement that 12 of the top clubs had agreed among themselves to form a European Super League (ESL) to replace the existing European Champions League (ECL). The “dirty dozen” were Real Madrid, Barcelona, Atletico Madrid, Juventus, Inter Milan, AC Milan, Manchester United, Manchester City, Liverpool, Arsenal, Chelsea, and Tottenham. These teams were to be joined by another 8, bringing the total up to 20. A defining feature of the ESL would be that 15 of its members would be guaranteed their place in the competition no matter how they performed the previous year or in their domestic competitions.