Just the shadow of a plant on the sidewalk in Franzensfeste, South Tyrol, which I liked. Photo taken in early May of 2021.

Category: Monday Magazine

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

On the Road: In Myanmar

by Bill Murray

Aye Chan Zin, a 22 year old competitive cyclist, once raced from Yangon to Mandalay and back. He fell and lost both incisors to gold teeth.

Aye Chan Zin, a 22 year old competitive cyclist, once raced from Yangon to Mandalay and back. He fell and lost both incisors to gold teeth.

“Road very bad out there,” he grinned, goldly.

Aye Chan was a child of privilege, a third-year vet school student with parents with government jobs. His dad was Chinese, a doctor working on a leprosy project, his mom a philosophy teacher at Yangon University. A family album they kept in the family car was chock full of smiling brothers and sisters.

He had his dad’s tan Toyota with tinted windows. He would be our guide and driver, and on Tuesday the seventh of February or, as The New Light of Myanmar newspaper called it, the eighth waxing of Tabodwe, 1356 ME, we set out from Yangon for a drive into the country. Read more »

To Understand the Mind We Must Build One, A Review of Models of the Mind – Bye Bye René, Hello Giambattista

“riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs” – so began James Joyce’s (infamous) Finnegans Wake. That line is but the completion of the book’s last sentence, “A lone a last a loved a long the”, You can, of course, stitch the two halves together in order simply by reading first this string and then that one.

Joyce was a notorious jokester. One of the jokes embedded in that first and final sentence is a pun on the name of a scholar who straddled the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Giambattista Vico. “Vicus” puns on the Latin for village, street, or quarter of a city and Giambattista’s last name. Just why Joyce did that has prompted endless learned commentary, none of which is within the compass of this essay, though, be forewarned, we’ll return to the Wake at the end.

Neither, for that matter, is Vico, not exactly. He had an epistemological principle: “Verum esse ipsum factum,” often abbreviated as verum factum. It meant, “What is true is precisely what is made.” In this he opposed Descartes, who believed that truth is verified through observation. Descartes, which his cogito ergo sum and his mind/matter dualism, is at the headwaters of the main tradition in Western thinking while Vico went underground but never disappeared, as Finnegans Wake bears witness.

Perhaps this century will see our Viconian legacy eclipse the Cartesian in the study of the mind. With that in mind, let’s consider Grace Lindsay’s excellent Models of the Mind.

What, you might ask, what kind of book is it? It could be a highly technical mid-career summary and synthesis, which would certainly be welcome. But no, it’s not that. It could be a text book for an advanced undergraduate or a graduate level course in neuroscience. It’s not that either. There are few footnotes, but each chapter has a reasonable bibliography at the back of the book. No, Models of the Mind is intended for the sophisticated and educated reader who is interested in how physics, engineering, and mathematics have shaped our understanding of the brain, to reprise the book’s subtitle. And that’s just the right audience if we want to pull off a paradigm change, from Cartesian to Viconian, in how we understand the mind.

It is intended for you, gentle reader. Read more »

Monday, May 17, 2021

Clearing the Decks

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Here’s a reasonable rule for critical discussion: all views for consideration should receive the same degree of scrutiny. Subjecting one account to a low level of critical evaluation, but another to a higher level, is not only unfair, but it clearly risks incorrect outcomes. In retrospect, it is easy to see how such a shift can occur, especially when the claims on offer are controversial and when one sees some in the conversation as adversaries or allies. When a person we despise says something, we might even positively want them to be wrong. So, when they say something anodyne, like the sky is blue, we may be motivated to reply in the following fashion:

Oh yeah? Well, sometimes, it’s red, purple, and yellow. That’s called sunset. And sometimes, it’s grey. That’s called overcast. Oh, and sometimes, it’s just black. That’s called night. Nice job overgeneralizing from sunny and cloudless days, you jerk.

You get the picture. Yet when a friendly interlocutor offers up the sky is blue, we tend to treat it with the modest degree of scrutiny that it calls for – as a general statement, with many exceptions. No problem.

One reason why the shift in critical scrutiny is hard to detect in situ is that it happens over time and with a background assumption about the exchange established in the process. This overall pattern we call the clearing the decks fallacy. Here’s how it unfolds. Step 1: Subject your opponents to the highest degree of scrutiny. Step 2: Once it is clear that the opponent’s views cannot satisfy that degree of scrutiny, conclude that they are nonviable and unsalvageable. Step 3: Pronounce your own view, but in a way that assumes that the appropriate degree of scrutiny has greatly diminished (after all, the opposition has been refuted). Step 4: If objections do appear, reply with a reminder of Step 2 – that the alternatives have been eliminated, so objections that must be based on their assumptions are undercut. It’s a neat dialectical strategy: one clears the decks of one’s opposition by adopting an unforgiving critical stance, but then one proceeds as if those same standards are inappropriate when it comes time to articulate one’s own view. In short, one applies demanding standards to clear the decks of one’s opposition, but then retracts those standards when presenting one’s own position once the opposition has been eliminated. Two features of the clearing the decks fallacy deserve emphasis. Read more »

Do Mention It

Editor’s Note: This essay once mentions a well-known racial slur. Indeed, much of the essay is about the usefulness of maintaining a distinction between using a word and merely mentioning it, and argues that mentions of even taboo words should be allowed, so it would be self-defeating to resort to euphemism in this case.

by Gerald Dworkin

For the past year or so there have been a considerable number of cases of teachers or authors or journalists who have been threatened with sanctions, had sanctions imposed, or lost their positions, because of articles they wrote or statements they made as part of their occupations. Many of these cases involved the appearance of the N-word in their speech or written work. Here are some of them.

For the past year or so there have been a considerable number of cases of teachers or authors or journalists who have been threatened with sanctions, had sanctions imposed, or lost their positions, because of articles they wrote or statements they made as part of their occupations. Many of these cases involved the appearance of the N-word in their speech or written work. Here are some of them.

1. In a course at the Rutgers Law School last Fall, a student was curious about why a defendant in a case was charged with conspiracy to murder, when he had not been directly involved in the shooting. So he looked up the case and found that the defendant had shouted that he was going to return to the scene where the shots were fired, but first, “I’m going back to Trenton to get my niggers.” This clarified for the student why the defendant might be charged with conspiracy to murder.

The professor of the course has asserted that she did not hear the word spoken during a videoconference session, which three students had attended after the criminal law class.

As the NY Times reported: “In early April, in response to the incident, a group of Black first-year students at Rutgers Law began circulating a petition calling for the creation of a policy on racial slurs and formal, public apologies from the student and the professor.”

At the height of a ‘racial reckoning,’ a responsible adult should know not to use a racial slur regardless of its use in a 1993 opinion,” states the petition, which was signed by law school students and campus organizations across the country.

“We vehemently condemn the use of the N-word by the student and the acquiescence to its usage,” the petition says.

To date the Professor has not apologized for her conduct and has not been sanctioned. Read more »

Monday Poem

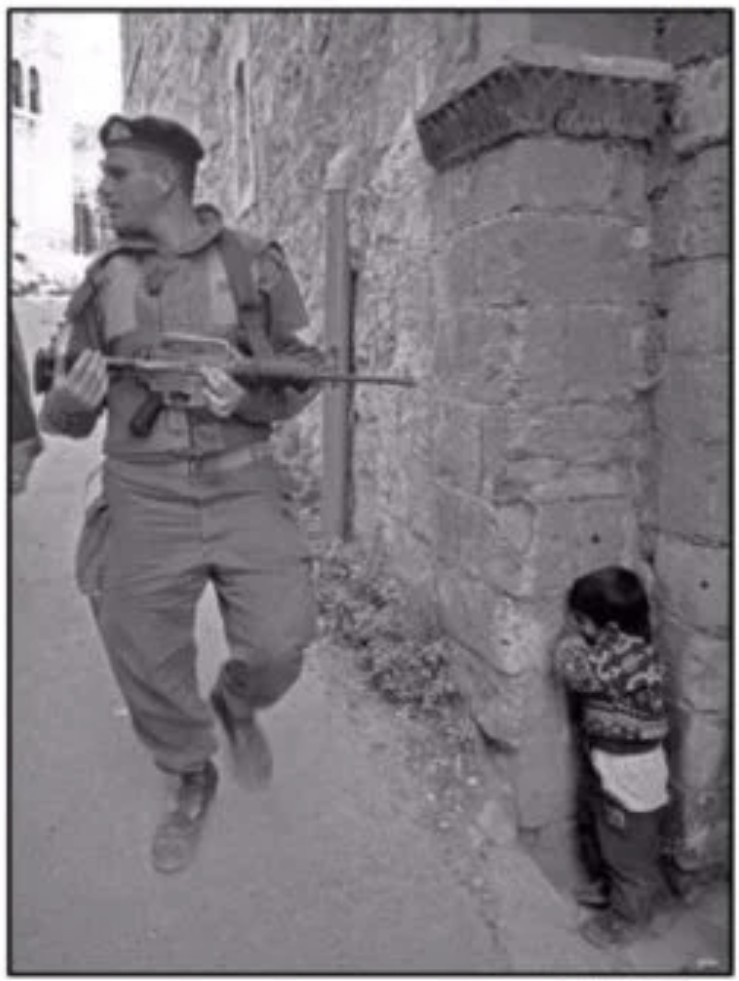

Please, See My Innocence

Please, See My Innocence

I am small and innocent

I’ve not yet had time to be

misshapen by adults,

but I know what they can do

so, at the sound of boots

I take refuge in this corner.

I hide my eyes believing

if I can’t see you, you can’t see me

but if you can, please, see also

my innocence

Jim Culleny

5/17/21

Oceans of Life

by Adele A Wilby

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ book, The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed is a triumph. The four major sections in the book, ‘Explore’, ‘Depend’, ‘Exploit’ and ‘Preserve’ are indicators of the breadth of issues addressed in the book: the variety of life forms in the different levels of the oceans; the significance of the oceans to life on the planet; the various ways in which human activity exploits the oceans resources, and concludes with her ideas about how to prevent the ocean from becoming just another area of resources of the planet for exploitation by human beings.

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ book, The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed is a triumph. The four major sections in the book, ‘Explore’, ‘Depend’, ‘Exploit’ and ‘Preserve’ are indicators of the breadth of issues addressed in the book: the variety of life forms in the different levels of the oceans; the significance of the oceans to life on the planet; the various ways in which human activity exploits the oceans resources, and concludes with her ideas about how to prevent the ocean from becoming just another area of resources of the planet for exploitation by human beings.

Most of us would have, at some point, looked out across an ocean enthralled by the natural beauty that it projects. However, anybody who has travelled on the ocean would also be aware of the vagaries of the moods that the oceans are capable of and wondered at their awesome power and potential, making them worthy of respect and caution when entering their watery domains. But it is quite extra-ordinary to realise that the beautiful vista of a mirror glass reflection on an utterly calm ocean or the wild raging of it waters is only a fraction of the oceans’ breadth and depth. As Scales tells us, the oceans take up seven tenths of the surface of the earth. The diverse topological structures and life on land are interesting enough, but the ‘expanses of the deep seabed, the abyssal plains and seamounts, canyons and trenches, plus all the water above them, constitute the single biggest living space on the planet’, a vast reserve of life being and waiting to be discovered and understood. Read more »

Perceptions

Sughra Raza. River Magic. May, 2021.

Sughra Raza. River Magic. May, 2021.

Digital photograph.

Three Poets from Small Presses: All the things of the world on fire

by David Oates

Small poetry presses are the gold dust of the publishing world, glittering yet easy to miss. And of enduring cumulative value.

Small poetry presses are the gold dust of the publishing world, glittering yet easy to miss. And of enduring cumulative value.

Of course the Big Five publishers will pick up suitably salable, already-famous, sure-thing poets. Penguin Random House publishes Terrance Hayes, and that’s a damn good thing, a Black poet of subtlety and immediacy; and Amanda Gorman, poet of the recent presidential inauguration; and Mary Oliver, who straddles the line between “accessible” and serious with an uncanny ease and a following most working poets cannot even imagine.

Meanwhile, as my previous essay here at 3QD proposed, the small presses do the nearly-invisible work of finding and developing new poets, and giving mid-career poets their next book or two, and taking risks with weird and strange and occasionally awful poets too. They do this the way ants collect morsels in the woods: because it is their nature.

(Fans of mixed metaphors may ask: So, are these ants collecting gold dust? And I reply: They are.)

In this essay, three books from contemporary poets whose work I admire. I read them to refresh my sense of the glorious possibilities of language. And to feel that while our public discourse may be as vicious as ever – perhaps even a little worse than the (miserable) average – yet in these small books from small presses, language may be transformative, life-giving, full of surprise and truth and therefore, hope. Read more »

Models of the Mind: A Conversation with Grace Lindsay

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Grace Lindsay is a computational neuroscientist at University College London. She has just published a new book titled “Models of the Mind: How Physics, Engineering and Mathematics Have Shaped Our Understanding of the Brain“.

Most books about the brain take either a biological or philosophical approach, but Grace’s book is rather unique in exploring the brain through the physical sciences and really delving deeply into how well or poorly mathematical models of the brain can provide insights into its complex functions. The book is not only wide-ranging in its choice of topics but is also a lively journey through the history of these efforts and traces the lives of the eccentric and fascinating scientists who were instrumental in figuring out the brain’s working by using tools ranging from information theory and graph theory to Bayesian modeling and neural networks.

Below I chat with Grace about “Models of the Mind”, a clearly written and highly recommended journey through the intricacies of an organ that is the essence of what makes us human.

Guessing With Physics

by David Kordahl

James Clerk Maxwell, whose theory of electromagnetism occupies the same physics pedestal as Newton’s theory of gravity, was by all accounts a good-humored and generous man, and a fairly confusing lecturer. Here is a story about Maxwell (admitted to be apocryphal in the math notes that recount it) that suggests something of his character:

Maxwell was lecturing and, seeing a student dozing off, awakened him, asking, “Young man, what is electricity?” “I’m terribly sorry, sir,” the student replied, “I knew the answer but I have forgotten it.” Maxwell’s response to the class was, “Gentlemen, you have just witnessed the greatest tragedy in the history of science. The one person who knew what electricity is has forgotten it.”

This anecdote—this joke—is improved for those who know Maxwell as the preeminent early theorist of electricity. After all, if Maxwell didn’t know how to define electricity, what hope was there for his students?

At risk of over-explaining it, this anecdote gestures toward a piece of insider knowledge. You don’t need to know everything to construct a mathematical theory, and mathematical theories can be more robust than the systems they have been constructed to describe. As I’ve written elsewhere, mathematical techniques that are useful in one area of science tend to be useful in in other areas, not as an exception, but as a rule. Read more »

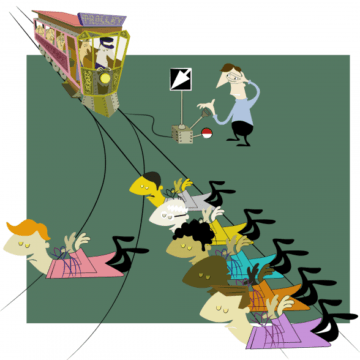

Other Trolley Problems

by Tim Sommers

The first part of the original trolley problem goes like this. A runaway trolley is careening towards five people tied to the tracks. There’s a lever in front of you that could divert it onto a second set of tracks. Unfortunately, there is also a person tied to those tracks. You can either do nothing and let five people die or throw the switch and kill one person – but save the five. What do you do?

The first part of the original trolley problem goes like this. A runaway trolley is careening towards five people tied to the tracks. There’s a lever in front of you that could divert it onto a second set of tracks. Unfortunately, there is also a person tied to those tracks. You can either do nothing and let five people die or throw the switch and kill one person – but save the five. What do you do?

The modern version of the trolley problem goes back to the 1960s, but there are variations that go back over 100 years. The trolley problem has been featured in video games, movies, tv shows, and has been a monster meme on the internet since at least 2016. MIT has a moral machine that does nothing all day and night but ask people questions based on the trolley problem – including variations suggested by users themselves. The trolley problem has been central to debates about how to program self-driving cars and “experimental” philosophers have spent a lot of time putting people in eMRI machines and asking them the trolley problem. But many other important trolley problems have not been fully explored. Here are just a few.

Sorites’ Trolley Problem

There’s no lever but the people tied to the tracks are pretty far away. Luckily, you have a wrench and can remove one piece of the trolley at a time. How many pieces do you have to remove for it to cease being a trolley? Which piece is the one piece that once removed will mean that the trolley is no longer a trolley?

Theseus’ Trolley Problem

Rather than simply removing pieces, you swap them out one at a time with brand-new, identical pieces. If you swapped them all out before the trolley hit anyone, would it still the same trolley? Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

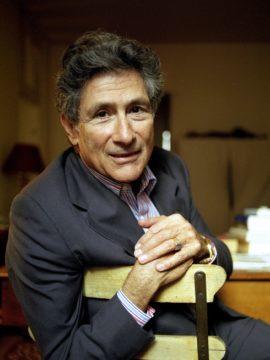

What Edward Said

by Claire Chambers

Few twentieth-century books witnessed Silver Jubilee celebrations but, 25 years after the publication of Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978), the monograph was commemorated in this way at his faculty in Columbia University, New York. Just a few months later, in September 2003, the Palestinian-American literary critic and theorist would die at 67 after protracted dealings with leukaemia. (This was the same group of cancers that had caused the quick and untimely death of one of his anticolonial forebears, Frantz Fanon, in 1961.) Said’s volume is routinely hailed in lists of the world’s most influential books. It also continues to shape the discipline of postcolonial studies which his work kickstarted. The Golden Jubilee in 2028 should be a grand affair.

Orientalism’s groundbreaking importance lies in the connections Said makes between culture and empire-building. He draws on Michel Foucault’s theories about the inextricable coexistence of power and knowledge, as well as Antonio Gramsci’s emphasis on the importance of culture in securing the consent of the dominated. In doing so, Said argues that colonization is not only about material acquisition. In addition to physically occupying other countries, colonizers seek to convey that their occupation is universally advantageous. It is absurd to watch the intellectual gymnastics they undertake in arguing that empire is good for both rulers and ruled. Read more »

George Saunders and Buddhist Literary Criticism

by Varun Gauri

For many of us, reading and writing literature is a spiritual endeavor. What does that mean?

In his book A Swim in the Pond in the Rain, George Saunders describes the benefits of reading and writing short stories using concepts familiar to Buddhists. In what follows, I list the Buddha’s Four Noble Truths and explore their relationship to literature, leaning heavily on Saunders’ account. Whereas my previous piece explored the implications of Saunders’ book for public narratives, here I focus on personal spiritual journeys. I close by raising questions about the evidentiary basis for these arguments.

Dissatisfaction, or suffering, is a basic fact of life

Buddhists often enumerate three types of suffering in our lives: the kind that comes from old age, sickness, physical pain, and death; the suffering that accompanies change, that sense that we can’t hold onto anything that we love, not permanently; and all-pervasive suffering, the background of fear and anxiety always with us, the sense that even our own existence is questionable, and that our relationships and personal lives will never live up to our hopes.

Saunders is especially interested in the last form of suffering — pervasive dissatisfaction. His account of the spiritual potential of literature focuses on its power to cause “an incremental change in the state of mind” in which, for a little while anyway, we become more alert to our lives and the presence of other beings — and less existentially dissatisfied. For Saunders, a crucial cause of this third type of suffering is miscommunication: We are egocentric and constantly talk past each other; as a result, we feel lonely and misunderstood. Egocentrism has an evolutionary origin— we are primed, for personal survival, to think that everything that is good for us is also good for everyone else. Tragically, that survival mechanism contributes to isolation and suffering. Read more »

Monday Photo

One can judge the depth of this otherwise very clear pond only by looking at the shadow of this bit of floating green algae. The upper part of the photo is also under water, there is just a reflection of a mountain there (rather than the reflection of bluish sky in the rest of the photo) so one sees the bottom even more clearly. Photo taken in Franzensfeste, South Tyrol, last week.

The International Patriot

by Chris Horner

How should people on the ‘progressive’ side of politics view patriotism? That question continues to vex those who would connect with what they suppose are the feelings of the bulk of the population. The answer will vary a good deal according to which country we are considering – the French left, for instance, has a very different relationship to la patrie to that of the US or the UK. In the case of the former, the side cast as traitors has historically been seen as the right. In the USA, at least in the second half of the 20th century it has been very different: those who protested against the Vietnam war were cast as the anti patriots. And today, we still hear that the left ‘hates our country’. The accusation is a damaging one, and has been wielded with glee by conservatives whenever they have the chance. So there is a tricky task for the left, it seems: to be seen as with and not against the mass of people in their identification with the nation and its history, without abandoning an internationalist perspective that rises above the narrow nationalism of the conservative.

How should people on the ‘progressive’ side of politics view patriotism? That question continues to vex those who would connect with what they suppose are the feelings of the bulk of the population. The answer will vary a good deal according to which country we are considering – the French left, for instance, has a very different relationship to la patrie to that of the US or the UK. In the case of the former, the side cast as traitors has historically been seen as the right. In the USA, at least in the second half of the 20th century it has been very different: those who protested against the Vietnam war were cast as the anti patriots. And today, we still hear that the left ‘hates our country’. The accusation is a damaging one, and has been wielded with glee by conservatives whenever they have the chance. So there is a tricky task for the left, it seems: to be seen as with and not against the mass of people in their identification with the nation and its history, without abandoning an internationalist perspective that rises above the narrow nationalism of the conservative.

I want to suggest here that we need to see that there is a problem with both the approach that seeks to inhabit the abstraction of simplistic universalism and the one that would rush into the warm embrace of parochial particularism (‘my country, right or wrong’ at its extreme). Instead, we need to see that the universal is something emergent, in and through the particular struggles and questions with which we are confronted. It is a concrete universal. Read more »

The Soul-Haunted War Poet Wilfred Owen

by Thomas Larson

Among the youngest and most soul-haunted poets who endured trench warfare during the First World War was Wilfred Owen—a British lieutenant, who died in France in 1918, one week before the Armistice. He was twenty-five. Owen was raised by an evangelical Anglican mother with whom he was abnormally close. She placed her provincial son into the service of a vicar—visiting the poor and sick, which Owen loathed—until he escaped and went to France in 1913. There, his faith began to unravel, declaring to her that “I have murdered my false creed.” War afoot, he returned to England and enlisted in the Artists’ Rifles, a British military order, rising quickly to officer. His fighting ability was tragically competent.

In April 1917, assigned a squad at the front, a shell exploded two yards from his head and he was severely concussed. Sent home, confused and shaky, he recuperated by writing. As his biographers note, the war was good for his poetry. His front-forged verse found its edge. He wrote brutal elegies for the lads he commanded and saw shot and with whom, as spirits, he communed. Dozens of men dead, their “unburiable bodies” lay as “expressionless lumps.” Freed from the horrors of gas and bombardment, “their spirit drags no pack, / Their old wounds, save with cold, cannot more ache.”

Such men were, in part, entranced by a three-hundred-year tradition of English Poetry, from Spenser to Sassoon, in which British boys were enchanted by the Romantic concept of the soul—whose life and death was given to love, honor, faith, courage, even the finicky rewards of verse. Read more »

Monday, May 10, 2021

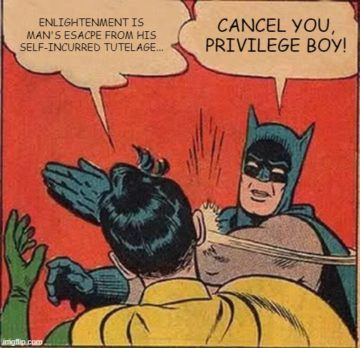

What is living and what is dead in the Enlightenment?

by Charlie Huenemann

Talking about “The Enlightenment”, when understood as something like “an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries” (thanks, Wikipedia), is like talking about Batman: do you mean classically heroic comic Batman? or the delightfully campy Adam West Batman? or the Batman of the movies, or of the gloomy Dark Knight era? The Batman one selects will determine what further questions need to be settled, and what scales of evaluation should be used.

Talking about “The Enlightenment”, when understood as something like “an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries” (thanks, Wikipedia), is like talking about Batman: do you mean classically heroic comic Batman? or the delightfully campy Adam West Batman? or the Batman of the movies, or of the gloomy Dark Knight era? The Batman one selects will determine what further questions need to be settled, and what scales of evaluation should be used.

Similarly, the Enlightenment can be seen as a cluster of philosophical values (placed upon individual liberty, human equality, political and scientific progress, and independence from religion), or the ways in which those values helped to form economic institutions (slavery of various forms, global capitalism, and free markets), or as a stand-in term for whatever deep injustice people think has become dominant over the last three centuries (global economic inequalities, political states favoring the wealthy, and enduring white privilege). It is often thought that the Enlightenment is somehow a single thing behind all these things, in the way some of us think there can be a steady “Batman” character behind his various depths and flavors.

These various flavors of “Enlightenment” are not wholly disconnected. For example, John Locke formulated a system of rights, contracts, and obligations that justified slavery on at least some occasions. The notion of actual human equality was interpreted by colonizers to mean potential human equality, which licensed the brutal process of more civilized nations forcing benighted savages into “more advanced conditions”. Scientific progress seemed to demand that we regard the natural world as a resource to be controlled and consumed, and soon our air became unbreathable. Freedom from religion came to mean that the only considerations that belong in the public sphere are measurements of material loss and gain; so “sin” and “virtue” need not apply.

And so, the criticism goes, the core ideals of Enlightenment lead to an alien and inhuman operating system that maximizes material well being for some, while annihilating any local traditions and values that are not readily uploaded into the system. Read more »

Of Mice and Moderna

by Mike O’Brien

I recently booked an appointment to be vaccinated. The provincial government here in Québec has opened up vaccine eligibility to people under 45 in 5-year tranches. 40-to-44-year-olds were able to log in to the health ministry’s web portal and book an appointment in a few minutes. A few days later, 35-to-39-year-olds were eligible, and few days after that, 30-to-34-year-olds, and so on and so on (to quote Zizek). I didn’t do much thinking about this decision. Within minutes of the portal opening I received two messages from friends, alerting me to hop on and register. The only consideration, besides getting the earliest booking possible, was which vaccine would be provided at which venues, and even that was a minor point.

Absent from my thinking was any question of whether or not I would get vaccinated at all. There is a growing concern about vaccine “hesitancy”, but this is still thankfully low in Canada relative to our (conservatively) 30% insane neighbours to the south. I have enough background in basic science and medicine to sort out the usual innumerate nonsense that underlies most resistance to vaccination. And while I do believe that there are nefarious, power-hungry cabals of conspirators perverting the workings of government, industry and public discourse, I don’t think that their schemes include putting mind-control chips into syringes. Why go to all that bother just to control people’s minds? That’s what media monopolies are for.

In a few years, we may discover that the vaccines have worrying side-effects. Or they may unexpectedly result in whiter teeth and clearer skin. From the limited vantage of the present moment, however, vaccination is an undeniably better bet for continued good health on the individual level, and so obviously beneficial to collective health that many sober minds might countenance making it obligatory. (I am on the fence about this. For context, note that I am also ambivalent about dispersing anti-mask protests with grapeshot. Happy 200th, Monsieur Bonaparte).

The lack of equivocation and hesitation in this decision bears a curious contrast with how I think about other areas of my health. Read more »