by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

I had been in Orvieto about a week, when a young American woman came up to me in the painted chapel and said, “Excuse me, do you speak English?”

Not waiting for my answer she continued, “Do you have any idea what these paintings mean?”

Looking at her astonished face, I gestured toward the eastern wall and whispered, “Well, over there is the Antichrist.”

Her friend joined us. They turned toward the wall where I was pointing and squinted.

“But he looks like Jesus Christ,” she said.

I handed her friend my fancy bird-watching binoculars and said,“Yes, but look at his face. See how Satan is controlling his movements? Like a puppet master.”

“What is this place?” Her friend with my binoculars asked.

“It is the Last Judgement, painted by Luca Signorelli in 1500.”

“It looks like a war.” She said.

“It is a war,” I responded.

2.

Sigmund Freud traveled to Orvieto in September of 1897. It was mere months after the death of his father, when he was still in the early days of his own self-analysis.

He would later pronounce the frescoes, “The finest paintings I have ever seen.”

Not only would Orvieto be one of the most significant pilgrimages of his life, but it would make a profound mark on his work, in the theory of repressed memories.

Has that ever happened to you? Where, not only do you forget a name or a person’s face, but another image floods into your mind, making it doubly hard to recall the forgotten person or thing. This recently happened to me when a friend asked me what happened to our high school friend John H. “Didn’t he die?” she asked. The moment she asked, an image of John G. flooded my mind. John G. took up all the space–and, as I

write this, I cannot recall what John H. looked like.

The way we sometimes substitute one name for another is known to us today as Signorelli Parapraxis. A form of “Freudian slip,” it transports us back to the days before Google, when people used to get tripped up by temporary forgetting, mis-readings and mis-writings. Nowadays, we just grab our mobile phones and “google it!” –when someone can’t come up with a name. But back in Freud’s day, people had to wait it out until someone could help them remember –or the person finally recalled the name for themselves. This was the origin of the Signorelli Parapraxis: when a year after seeing the frescoes in Orvieto, Freud, in casual conversation with someone he had met on a train, was unable to remember Signorelli’s name. He could visualize the colors and figures in the frescoes, but for the life of him, he couldn’t recall the name of the painter. It took several days, which Freud described as being an “inner torment,” before he remembered the painter’s name.

But how could Freud forget the name of his favorite painter? Freud himself would ponder this question in great depth, not only writing three different and opposing accounts of what happened on the train that day, but concluding that the forgetting was caused by a form of repression. He was, after all, working on the puzzling case of Anna O at the time.

3.

It was my second visit to see the frescoes. And this time, I had come prepared for anything, planning to spend at least a week.

The Duomo opens early in summer. Arriving each day as they opened the large bronze doors, I’d often have the chapel to myself for over an hour. It was beautiful in the mornings, when the light streamed in through the south-facing windows, lighting up the paintings on the east wall:

The Rule of the Antichrist and the Coronation of the Elect

I also enjoyed being there later in the day, when the chapel was packed full of sightseers and religious pilgrims. They always entered in large groups. Like the tide coming in, they would flow into the small room, quickly filling up the space. Whenever this happened, I’d step out of the chapel and watch them collectively have their minds blown.

And I wondered how many of them would become so haunted by what they were seeing that they would dream of coming back, as I had.

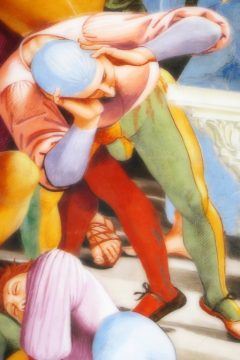

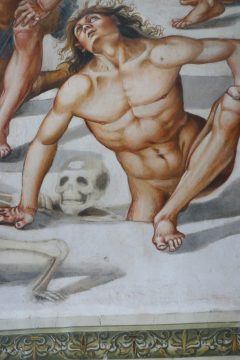

As their guide whispered explanations into a microphone, they would slowly rotate in unison—like a giant sunflower tracking the movement of the sun. They were following the strict theological program set out by Signorelli five hundred years ago. From the Rule of the Antichrist and the End of the World to the Resurrection of the Dead and the Damned Entering Hell, their faces would grow increasingly dark with worry and alarm. Not even the Catholic pilgrims in robes and sandals seemed comfortable, as they watched the teeming population of the damned being tortured by terrifying demons painted in other-worldly colors all writhing together in the maelstrom of Signorelli’s version of Hell.

A particularly famous detail from this fresco is of a young woman being borne on the back of a horned demon in flight. She is completely naked and looking back in horror from the place where the angels of God guard the gates of heaven so no sinners can enter. With her long blonde hair, one of the guides–an old timer it seemed– suggested that Signorelli had painted the likeness one of his previous mistresses in this role as female captive. The leering demon resembled a butcher hauling an animal back to his lair to be skinned and eaten.

In the evenings, the chapel would grow quiet again.

The light gone; the paintings shimmered in the shadows. With the chapel emptied of people, I liked to stand silently in front of Signorelli’s haunting Pieta, which was painted into a niche in the western wall. A guide mentioned that Signorelli painted the pieta just after losing his son to sickness. After hearing that, I could hardly hold back the tears when I stood in front of it.

When closing time came just after six, the guards couldn’t bring themselves to tell me I had to go. Pointing at their watches, they would ask me how long I wanted to stay. I nodded and would take my leave. I knew I would be back again the next morning, for like Freud, the frescoes had exerted a profound power over my imagination.

1447

4.

The Orvieto Duomo is one of the most beautiful Gothic cathedrals in Italy. Only an hour or so north of Rome, the sight of the medieval walled town perched atop a promontory of soft volcanic rock—seven hundred feet above the valley below—is unforgettable. As tourists do today, Freud’s itinerary began at the cathedral, after which he explored the Etruscan caves and graves. Was it merely the splendor and power of the paintings that later caused Freud to forget in such a dramatic way—or was it some combination of the paintings seen just before descending underground to see the caves?

The heart of Orvieto has always been the cathedral. Surprisingly grand for such a small town, it is built of alternating stripes of black and white marble in the Sienese style. Work was begun in the late 13th century to house an important relic. And no cost was too great in its construction. From the dazzling mosaics that adorn the façade to the many works of sculpture both on the exterior and interior of the cathedral, some of the greatest names of early Renaissance Tuscan art had a hand in its decoration.

But it is the Chapel of the Madonna di San Brizio that brings art historians from all over the world to come and kneel down to its glories.

But it is the Chapel of the Madonna di San Brizio that brings art historians from all over the world to come and kneel down to its glories.

From its very inception, every surface of the chapel was to be covered in frescoes.

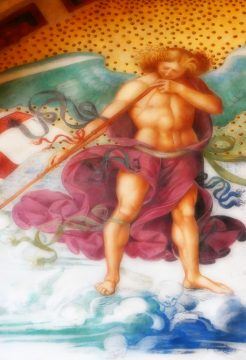

The first artist employed to decorate its walls was Fra Angelico. “Famous above all Italian painters,” stated the contract he signed around 1447. Unfortunately, so beloved was this painter by Pope Nicolas V, that he was called back to Rome after completing only two paintings on the vault:

The Christ in Judgment and Angels and Prophets.

I overheard a guide telling her group that, while people don’t come to the chapel to see these works by Fra Angelico, over the years she has come to feel they are superior to the more famous ones by Luca Signorelli. She told her captive audience about a time during the restoration of the frescoes, when guides were allowed to climb up the scaffolding nearly to the ceiling.

“And the details were perfect,” she said. “Signorelli painted to impress the people standing on the ground, while Angelico painted for God’s eyes.”

Though unable to get any closer than where I was standing, feet firmly on the ground, still I could understand what she meant. Angelico’s paintings exude a peaceful tranquility in what is an otherwise pretty disturbing space. With Christ depicted as Judge in the Byzantine fashion, he is seated on a cloud and crowned with a nimbus halo.

The cathedral authorities had wanted Perugino to take over after Angelico dropped out. But that contract fell through, so work on the chapel was stalled for almost half a century. And by the time Luca Signorelli picked up the mantle in 1499, times had changed, and Italy was in the throes of millenarianism.

5.

Remember how you partied in 1999? I celebrated the new millennium in Hong Kong, with fireworks and people joyously laughing and dancing in the streets. There was some paranoia about the dreaded Y2K, as we anticipated all the computers of the world melting down, leaving us in medieval darkness. But none of that came to pass. In fact, for such a huge event—a new millennium upon us—it was surprisingly lacking in drama.

That would change.

While the New Year passed without incidence, the first two decades since have become darker. Climate scientists began ringing alarm bells and speaking of coming calamities. The Doomsday Clock was also recently moved to 100 seconds to midnight – which is closest point to nuclear annihilation since Cold War.

And now the pandemic.

Perhaps even more than we do now, the Italians of 1500 had good reason to fear the end was coming, with French invasions, sightings of ominous blood red clouds and ultimately a massive outbreak of the plague in the final days of the 13th century. It is not hard to imagine people would feel apocalyptic and wonder, “Is this it?”

Perhaps even more than we do now, the Italians of 1500 had good reason to fear the end was coming, with French invasions, sightings of ominous blood red clouds and ultimately a massive outbreak of the plague in the final days of the 13th century. It is not hard to imagine people would feel apocalyptic and wonder, “Is this it?”

With so much at stake, one had to get things right. After all, this could mean an eternity in heaven or in hell, right?

The first time I saw Signorelli’s Rule of the Antichrist –on the eastern wall–just like the young American tourists I met, I assumed the figure in the center was Jesus Christ. I didn’t have much time that trip and was only in the chapel for twenty minutes. But it bothered me once I got back home. Why was Satan whispering in the ears of the Christ? My own interest in the frescoes probably began with that mistake, because it nagged at me for quite some time, especially when I learned Signorelli had studied under my favorite painter in the world, Piero della Francesca.

In retrospect, it should have been obvious. We see the signs he is not the real deal; for despite superficially looking very much like Jesus and despite his performing miracles right in front of our eyes, such as raising the dead, we clearly see horned Satan with his black armies re-taking the Third Temple in the background.

On my recent trip, I overheard some of the guides suggesting that Signorelli’s antichrist was supposed to be the heretical priest Girolamo Savonarola, who had been burnt at the stake in Florence for such apocalyptic fear mongering. Many at the time considered him to be a saint—but the Pope begged to differ. And in fact, others thought Signorelli’s antichrist was the Borgia pope.With so much at stake, artists sure didn’t make things easy. I was reminded of a comment I received to something I had written here in these pages a few years ago about our current calamitous state of affairs in which I was told, “Don’t you get it? Trump is the Second Coming of the Lord.” And so this all continues…

6.

So, what happened to Freud?

Whatever happened that day in Orvieto, it doesn’t appear to have been something relating to apocalyptic visions (as it had been for me).

The Great Man himself claimed that there was nothing whatsoever in the content of the frescoes to explain his forgetting Signorelli’s name. The forgetting occurred while on a train –about a year after his trip to Orvieto. He was traveling through Bosnia- Herzegovina. Talking with a person sharing his compartment, he says he simply blocked the name because his psyche was trying to forget something else, namely the suicide of one of his patients in the town of Trafoi, in South Tyrol.

Freud describes that in trying to recall the name “Signorelli,” the name Botticelli and then Boltraffio kept forcefully popping into mind.

But there is more. Looking at the diagram makes it easier to grasp.

In a series of LINGUISTIC LINKAGES, Freud said he was connecting the first part of the word Signorelli with the German for Signor=Herr, and the second syllable of Herzegovinina (Hertz=Heart). On the train, his traveling companion had been discussing the sexual practices of Turks (basically that they valued it a lot!) and poor Freud was overcome.

Further, Freud argued that (Bo)snia linked (Bo)tticelli with (Bo)ltraffio and Trafoi. He concludes by saying: “We shall represent this state of affairs carefully enough if we assert that beside the simple forgetting of proper names there is another forgetting which is motivated by repression”.

One of my tour guides in Orvieto preferred Lacan’s suggestion that in forgetting “Signorelli’s name he was effacing his own first name Sigmund.

If you are thinking this is getting weird, you are right.

Scholars continue to debate whether it wasn’t something else that had haunted Freud’s psyche after his trip to Orvieto. Perhaps it was the homoerotic imagery that was to blame? Or perhaps it was facing the Father (Freud’s father had just died) and the experience of death, when descending into the Etruscan caves? (Freud would dream about this).

7.

7.

Back home, a few days before the mandatory lockdown in California, we visited my mom about an hour away from our place in Pasadena. It was pouring rain, and I saw the man when we were stopped at a red light. We had just exited the freeway. My husband was driving so kept his eyes on the light, but I saw the homeless man standing in the rain immediately. He had one of those plastic disposable rain coats people sometimes toss in their suitcases before they travel—never really expecting to have to use it. Not seeking shelter, not showing emotion, he just stood there, looking hungry and cold. Eyes wide and haunted, he seemed to look right through me. When the light changed to green, my husband hit the gas and drove the last few blocks home, as I sat there paralyzed by anxiety. He could have been in Signorelli’s End of Days.

I was filled with self-loathing that we didn’t do something, instead of just sitting there in horror at the world.

That was the last time I left the house. During the past several months of lockdown, I have found myself thinking of the End of Days frescoes constantly, especially the painting depicting the communal harmony of heaven–where people worked together. It wasn’t just something seen, but heard–the paintings become –again– Dante’s journey from cacophony to polyphony. People have compared Old Master paintings to particular pieces of music–from cacophony to polyphony. For example, legendary art historian Bernard Berenson declared the angels of Titian’s Assumption of the Virgin to be “Embodied joys, acting on our nerves like the rapturous outburst of the orchestra at the end of “Parsifal.” And I would argue that Piero’s True Cross Frescoes are like Beethoven’s Cavatina. In this way, Weber compares the Signorelli frescoes to a symphony by Tchaikovsky at the apogee of force, every instrument of the orchestra performing simultaneously.

To say this work of art had made a deep impression on me –as it had on Freud–would only be an understatement, for the changed the way I see the world.

To say this work of art had made a deep impression on me –as it had on Freud–would only be an understatement, for the changed the way I see the world.

Still, Freud’s choice of Signorelli’s frescoes as the finest paintings he had ever seen was an odd one. I think many people would agree with me that Signorelli’s teacher Piero della Francesca (my own favorite painter) was the vastly better artist. Though Signorelli started off as an apprentice in Piero’s studio in Arezzo, his work lacks the sublime transcendent quality of that of his teacher’s. It is also missing the “more-real-than-real” vibrancy of Mantegna. And even fans of the robust style usually go for Michelangelo or Tintoretto. And speaking of Michelangelo, you won’t be too surprised to hear that when Michelangelo stopped at Orvieto to see Signorelli’s frescoes, he intended to stay for a day and instead stayed several weeks. Giorgio Vasari, the Florentine father of art history, counted this as a decisive influence, “as anyone can see,” in Vasari’s words, on Michelangelo’s “Last Judgment” in the Sistine Chapel. So it wasn’t just Freud and Leanne who became a bit obsessed.

It’s true! Great art works intensify our feelings of being alive. The puzzle-like quality can exert power over our imaginations and help make meaning of our lives even hundreds of years after they were created. Las Meninas was like that for some, Durer’s rhinoceros was like that for others. Freud probably did not meet the Antichrist at Orvieto. I think it is safe to say he met his Father. I guess it was me who met the antichrist, as the image of that particular fresco has bothered me for years, especially these days. But not only these days. As Mark O’Connell says in his Notes from an Apocalypse, it has always been the end of days. As you might know, the term Apocalypse, means an unveiling. Like this virus. We are seeing things crack open along existing vulnerabilities and seeing the world as it really is. This is what Signorelli was trying to describe. And it is incredible that the work of art is still “working” to do this five hundred years after it was painted. O’Connell makes the point that in the old days, it was God who would spare the righteous and see the rest were cast into flames. -But now–and this is the truth of now– it’s all up to the market.

On my last day in Orvieto, another person walked up to me. This time he was speaking quickly in Italian. Pointing at the painting of the Madonna on the altar. When he saw I wasn’t following him, he switched to German and said the word “icon,” he was so deeply moved by the votive image.

On my last day in Orvieto, another person walked up to me. This time he was speaking quickly in Italian. Pointing at the painting of the Madonna on the altar. When he saw I wasn’t following him, he switched to German and said the word “icon,” he was so deeply moved by the votive image.

Madonna della Tavola, Madonna della Tavola, he repeated.

No one stops to look at this simple image–not painted by the great artist–but rather is much older (late 13th – early 14th century), ensconced in a late baroque marble altar. It is, in fact, the very reason for the chapel. The man was weeping. And I couldn’t help but be impressed by him–surrounded by all the surreal images and dazzling colors of Signorelli, he kept his eye on the ball.

MINI-SYLLABUS: WHEN FREUD MET THE ANTICHRIST AT ORVIETO

Further Reading:

Eyes Swimming with Tears, by Leanne Ogasawara

Best Picture in the World, by Leanne Ogasawara

Being Alone with Las Meninas, by Leanne Ogasawara

Framing Nature, by Brooks Riley

Freud’s Trip to Orvieto, by Nicholas Fox Weber

Seen from Behind: Perspectives on the Male Body and Renaissance Art

by Patricia Lee Rubin

Luca Signorelli –written in 1899 (to enjoy how different art history was back then)

by Maud Cruttwell