I don’t remember when it was, but it was years ago, before religion had become such a prominent factor in American politics. Perhaps it was during my graduate school years, the mid-to-late 1970s. Whenever, it came as a shock to learn that America was more religious than Europe. It’s not so much that I had thought the reverse. I rather doubt that I’d thought much about it one way or another. The shock, I suppose, was simply that America was such a religions nation.

Religion has been much more visible in American politics of the last two decades and America remains more religious than Europe. This would come as no surprise to readers of Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, but I hadn’t read it and, to be honest, still haven’t (though I’d read The Ancient Regime and the Revolution years ago). I have, however, read The Fourth Great Awakening & the Future of Egalitarianism, by the economic historian and Nobel Laureate Robert William Fogel. Fogel argues that American society and culture has been driven by cycles of religious revival. The first three cycles, starting in roughly 1730, 1800, and 1890, have been recognized in standard religious history, while the Fogel himself has proposed the fourth, dating it to the 1960s. He characterizes it as a “return to sensuous religion and reassertion of experiential content of the Bible; rapid growth of the enthusiastic religions; reassertion of concept of personal sin; stress on an ethic of individual responsibility, hard work, a simple life, and dedication to family.”

I rather doubt that either Tocqueville or Fogel would have predicted that one day the United States Capitol Building would be stormed in the names of a recently defeated President, Donald Trump, and God, with many of the belligerents believing Trump to be God’s instrument. They would have found that shocking. I did, as did many other Americans.

To put the question in its starkest form: How is it, then, that religious belief can be both foundational to American democracy and a profound threat to it? Read more »

Let’s talk about voter suppression. Not about whether it’s good or bad or legal or moral (you can get more than enough of that virtually 24/7), but about what practical implications it might have.

Let’s talk about voter suppression. Not about whether it’s good or bad or legal or moral (you can get more than enough of that virtually 24/7), but about what practical implications it might have.

I discovered my ideal radio station by accident.

I discovered my ideal radio station by accident.

I’ll return to that second crack once we’ve explored the first one. But why do that at all? Does free will matter to anyone but a couple of bickering philosophers? Of course it does! Sam Harris noted in his recent

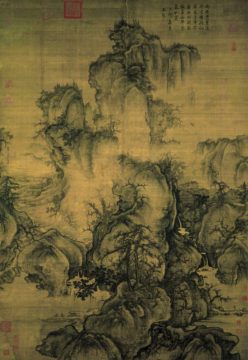

I’ll return to that second crack once we’ve explored the first one. But why do that at all? Does free will matter to anyone but a couple of bickering philosophers? Of course it does! Sam Harris noted in his recent  “Sadequain!” The very name is like a magic word that triggers a tumult of images in the mind. Arguably, no Pakistani artist has elicited more admiration, evoked more passion, and received more adulation than Saiyid Sadquain Ahmad Naqvi, the subject – and really, the hero – of the book “Sadequain: Artist and Poet – A Memoir” by Saiyid Ali Naqvi. In the world of art, be it painting, music, or literature, it is the pinnacle of achievement to be recognized by a single name – to need no further introduction. And rare indeed is the artist who achieves this distinction in his or her own life, as Sadequain did remarkably early in his career as an artist. And this delightful, beautiful, and insightful book shows why. Beginning with the earliest and formative years of Sadequain when he was not yet a legend, it takes the reader systematically through all stages of his life and his growth as an artist, laying bare both the immense determination and the perpetual restlessness of the artist’s genius.

“Sadequain!” The very name is like a magic word that triggers a tumult of images in the mind. Arguably, no Pakistani artist has elicited more admiration, evoked more passion, and received more adulation than Saiyid Sadquain Ahmad Naqvi, the subject – and really, the hero – of the book “Sadequain: Artist and Poet – A Memoir” by Saiyid Ali Naqvi. In the world of art, be it painting, music, or literature, it is the pinnacle of achievement to be recognized by a single name – to need no further introduction. And rare indeed is the artist who achieves this distinction in his or her own life, as Sadequain did remarkably early in his career as an artist. And this delightful, beautiful, and insightful book shows why. Beginning with the earliest and formative years of Sadequain when he was not yet a legend, it takes the reader systematically through all stages of his life and his growth as an artist, laying bare both the immense determination and the perpetual restlessness of the artist’s genius.