How do we get there from here? Evolution, revolution, or revolution through evolution? I don’t know, but as the smart kids are saying these days, I have my priors. As does everyone else.

A movement begins

Back in July 2019 Patrick Collison and Tyler Cowen called for a science of progress in an article in The Atlantic. The article generated a fair response, some in favor, some pushing back – Collison has collected some of the responses here – and people have begun conversing and gathering around the idea of progress studies. The purpose of this post is to take a quick look at what has been going on and a somewhat

more considered look at what needs to happen if an interest in progress studies is to yield discernible progress.

Let’s begin with a passage from Collison and Cowen, “We Need a New Science of Progress”:

By “progress,” we mean the combination of economic, technological, scientific, cultural, and organizational advancement that has transformed our lives and raised standards of living over the past couple of centuries. For a number of reasons, there is no broad-based intellectual movement focused on understanding the dynamics of progress, or targeting the deeper goal of speeding it up. We believe that it deserves a dedicated field of study. We suggest inaugurating the discipline of “Progress Studies.”

Before digging into what Progress Studies would entail, it’s worth noting that we still need a lot of progress. We haven’t yet cured all diseases; we don’t yet know how to solve climate change; we’re still a very long way from enabling most of the world’s population to live as comfortably as the wealthiest people do today; we don’t yet understand how best to predict or mitigate all kinds of natural disasters; we aren’t yet able to travel as cheaply and quickly as we’d like; we could be far better than we are at educating young people. The list of opportunities for improvement is still extremely long.

Mark their reach: cure all diseases, solve climate change, world’s population live comfortably, predict and mitigate natural disasters, travel cheaply, educate all young people well. The words are easy to comprehend, and those two paragraphs are relatively short. But they are talking about human life on earth, all of it, going forward. Can you get our mind around it, your hands? Really? It’s beyond my grasp.

They go on : “Progress Studies is closer to medicine than biology: The goal is to treat, not merely to understand.” Given their reach, if not their grasp, just what would treatment, the laying on of hands, entail?

Treatment is oriented toward the future. Thinking about the future is tricky. It is one thing for a physician to devise a treatment plan for an ailment that is well studied. It is quite something else to steer society – the world! – into a future that is unknown and unknowable. How do you devise and execute a treatment plan for that? I don’t know, but I’m sure that studying what has already happened, however necessary and useful it may be, is not sufficient. Something else is required, something more like fiction. Imagine a hundred futures, each in devilish detail, pick the ones you like, and figure out how to keep on one of those courses.

Are you ready to play chess with the Devil?

Change, incremental or foundational?

What do those words even mean? A first crack:

- Incremental: The basic structure of the human world is serviceable. We can achieve progress by tweaking parameters of existing practices and institutions.

- Foundational: Existing practices and institutions are no longer adequate to the challenges we face. We need new ones.

Of course we should examine history to see what has happened in the past and then see which cases best fit the present moment. But we may not always find suitable parallels.

Where does the Progress Studies movement stand on this issue? I would assume that it varies from person to person, but that it’s mostly up in the air because the question hasn’t been explicitly proposed and thrashed out. It smells to me, though, that the Progress Studies movement leans toward incremental change, if only by default. It is much easier to think about modifying what we’ve got than creating something new (from the ground up).

How do we increase innovation in scientific research? Do we offer more prizes, award more grants to younger investigators, more long-term grants, reduce the burden of reporting overhead? Those things preserve the current practices and institutions, but tweak the parameters. Perhaps we should dismantle the current university research structure and replace it with…whatever…a thousand blooming flowers? That’s more like foundational change.

The blog Tyler Cowen runs with Alex Tabarrok, Marginal Revolution, is subtitled: “Small Steps Toward a Much Better World”. That sounds like parameter tweaking. But how many, how much and for how long? Is that much better future world structurally like the present one or has the long course of incremental change morphed into foundational change – think of the caterpillar and the butterfly? But think of the caterpillar and the butterfly. From moment to moment there is incremental change. Over the longer term we see that where once a caterpillar crept along leaf and twig, now a butterfly flits from flower to flower. Fundamental change: Marginal revolution?

The blog Tyler Cowen runs with Alex Tabarrok, Marginal Revolution, is subtitled: “Small Steps Toward a Much Better World”. That sounds like parameter tweaking. But how many, how much and for how long? Is that much better future world structurally like the present one or has the long course of incremental change morphed into foundational change – think of the caterpillar and the butterfly? But think of the caterpillar and the butterfly. From moment to moment there is incremental change. Over the longer term we see that where once a caterpillar crept along leaf and twig, now a butterfly flits from flower to flower. Fundamental change: Marginal revolution?

Cowen puts growth at the center of his thinking, as many economists do. And growth is driven by compounding returns on investment. In his well-known essay, “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren” John Maynard Keynes observed:

The modern age opened; I think, with the accumulation of capital which began in the sixteenth century. I believe…that this was initially due to the rise of prices, and the profits to which that led, which resulted from the treasure of gold and silver which Spain brought from the New World into the Old. From that time until today the power of accumulation by compound interest, which seems to have been sleeping for many generations, was re-born and renewed its strength. And the power of compound interest over two hundred years is such as to stagger the imagination.

However, back in 1972 the Club of Rome famously proposed that there are limits to growth. An economics of limits seems to me foundationally different from one of compounding growth. I do not know when or even if we face such limits, but the earth is finite, and moving to the stars and planets seems extraordinarily costly for the foreseeable future. Can we nonetheless prosper and progress in the face of finitude? Can we have economic growth in the world of bits and bytes while maintaining a steady-state in the world of atoms?

Now, consider the first quarter of the 20th century. Everything changed. The arts saw abstraction and surrealism begin to displace figurative painting and drawing. Atonality enters classical music while jazz (swing) revolutionizes popular music. The modern novel is born: Ulysses (1922), The Sun Also Rises (1926), Mrs. Dalloway (1925), The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933), Death in Venice (1912), and so forth. The automobile emerged as a major new mode of transportation and airplanes developed to the point they could be used in aerial combat. Motion pictures and radio became major forms of popular entertainment. Then we have the Russian Revolution (1917-1923), which overlapped with World War I (1914-1918). The first unleashed a new form of modernity while the second reworked the map of Europe. And so forth.

Can we get from the world of 1900 to that of 1930 though nothing more than incremental change in procedures, mechanisms and devices, buildings, and modes of social organization that existed in 1900? I do not think so. Is the current world undergoing changes of a similar depth and magnitude magnitude?

Decadence

When Ross Douthat talks of decadence, he isn’t using the word in its usual sense – as my dictionary says – as a “moral or cultural decline as characterized by excessive indulgence in pleasure or luxury”. He uses the term to mean cultural exhaustion. Nothing really new is forthcoming, though there may be lots of motion. He begins his book, The Decadent Society, by invoking the moon landing of 1969:

The peak of human accomplishment and daring, the greatest single triumph of modern science and government and industry, the most extraordinary endeavor of the American age in modern history, occurred in late July in the year 1969, when a trio of human beings were catapulted up from the earth’s surface, where their fragile, sinful species had spent all its long millennia of conscious history, to stand and walk and leap upon the moon.

“Four assassinations later,” wrote Norman Mailer of the march from JFK’s lunar promise to its Nixon-era fulfillment, “a war in Vietnam later; a burning of Black ghettos later; hippies, drugs and many student uprisings later; one Democratic Convention in Chicago seven years later; one New York school strike later; one sexual revolution later; yes, eight years of a dramatic, near-catastrophic, outright spooky decade later, we were ready to make the moon.” We were ready—as though the leap into space were linked, somehow, to the civil rights revolution, the baby boomers coming into their own, the transformation in music and manners and mores, and the hopes of utopia percolating in Paris, Woodstock, San Francisco.

Mailer’s was a mystical take on history, but one well suited to its moment. For the society that made it happen, the Apollo landing was both a counterpoint to the social chaos of the 1960s and the culmination of the decade’s revolutionary promise. It proved that the efficiency and techno-optimism of Eisenhower-era America could persist through the upheavals of the counterculture, and it represented a kind of mystical, dizzy, Age of Aquarius moment in its own right. […]

The Apollo program came to an end in December 1972.

NASA shifted its man-in-space efforts to the shuttle; but low-orbit transfer, no matter how useful, just doesn’t spark the imagination like landing on the moon. Many of NASA’s best people began to leave. Space Transportation, Inc. is not what they’d signed up for. NASA had become decadent.[1]

Chaos continued in the larger world. Since then we’ve had a disastrous string of wars in the Middle East stretching for 2003 to the present, a financial collapse in the middle of it, and now a growing opioid epidemic. Global warming was not an issue when Apollo 11 landed on the moon. It certainly is now. Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005 and Hurricane Sandy tore up the East Cost of the United States in 2012, flooding the subways in New York City and putting out the lights.

I was living in Jersey City at the time, across the Hudson from Manhattan. I was out of my home for several days; but others were out for weeks. Some lost their homes. A local marina scattered its boats on land.

I was living in Jersey City at the time, across the Hudson from Manhattan. I was out of my home for several days; but others were out for weeks. Some lost their homes. A local marina scattered its boats on land.

Then we have the computer. They were room-filling behemoths in 1969; only a few people had direct access to them. Now they are everywhere. While the internet has afforded us increased avenues for personal expression and exploration, and has put the world’s knowledge at our finger tips – though one must sometimes fork over a toll at a pay wall – social media has fractured public discourse and contributed to the degradation of civil society.

However the computer has fostered doubts about just who and what we are. “Do not fold, spindle, or mutilate” became a watchword of the 1960s and 1970s. It had been printed on the punch cards that were used for computer data entry in the early days of computing and came to symbolize humans being swallowed up by “the machine”. In 1968 Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey became one of the earliest, if not the earliest, movies to feature an artificial intelligence that pursues its relentless logic at the expense of human life. Such AIs have become ubiquitous in film and fiction. Otherwise serious pundits, philosophers, and divines debate whether or not we are living in a computer simulation. How can we look forward to a future offering more of THAT?

Such is the decadent era through which we are living. Are we living in a psycho-cultural-social chrysalis? What will the world be like when we come out, if indeed, we come out at all?

Experiments in Living: Science Fiction

Is our passage through the chrysalis utterly beyond our control? Do we have no say in what the world will be like when we emerge?

Of course not.

Citing the Center for Science and the Imagination at Arizona State University, Cowen and Collins acknowledged a role for science fiction in thinking about the future. But experiencing fiction is more than thinking. It is a simulation of living. And can be preparation for living in new ways.

The late Wayne Booth noted, “Each culture provides every member with an unlimited number of “natural” choices that seem to require no thought” (The Company We Keep: An Ethics of Fiction, p. 484). “But how” he goes on to ask, “should we make those choices?” We take advantage of the fact that fiction is a “relatively cost-free offer of trial runs”. Literary experience simulates life. Booth observes:

If you try out a given mode of life in itself, you may, like Eve in the garden, discover too late that the one who offered it to you was Old Nick himself…In a month of reading, I can try out more “lives” than I can test in a lifetime.

In a world that’s changing as rapidly as ours, but with so little sense of progress, it is especially important that we try out alternative lives.

When he was interviewed in The Paris Review, 2011, science fiction writer Samuel R. Delany said:

Science fiction isn’t just thinking about the world out there. It’s also thinking about how that world might be—a particularly important exercise for those who are oppressed, because if they’re going to change the world we live in, they—and all of us—have to be able to think about a world that works differently.

How the world might be, that’s what we should think about. Those are the lives we must experience.

Writing just the other day in The New Yorker, Kim Stanley Robinson said:

… science fiction is the realism of our time. The sense that we are all now stuck in a science fiction novel that we’re writing together—that’s another sign of the emerging structure of feeling.

Science-fiction writers don’t know anything more about the future than anyone else. Human history is too unpredictable; from this moment, we could descend into a mass-extinction event or rise into an age of general prosperity. Still, if you read science-fiction, you may be a little less surprised by whatever does happen. Often, science-fiction traces the ramifications of a single postulated change; readers co-create, judging the writers’ plausibility and ingenuity, interrogating their theories of history. Doing this repeatedly is a kind of training. It can help you feel more oriented in the history we’re making now. This radical spread of possibilities, good to bad, which creates such a profound disorientation; this tentative awareness of the emerging next stage—these are also new feelings in our time.

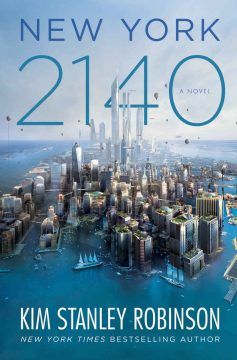

It is in that spirit that I approached Robinson’s New York 2140 two years ago. I was thinking about global warming, as I often do, and thinking in particular that we might no be able to prevent the seas from rising to an uncomfortable degree. Of course I don’t know that that will happen, no one does – and, for that matter, it isn’t something I am likely to face – but we need to think about it, to consider the possibilities, as we work our ways through the many trade-offs we will be facing.

If the seas rise catastrophically, will the resulting world be a livable one? That’s the question Robinson asked in New York 2140. The seas have risen 50 feet in two major “pulses” (that have taken place before the story begins). There have been technological advances, but no space travel (none is depicted in the book), and no human-level artificial intelligence. But the basic political and economic structure of the world appears to be the same as our current world, hence Robinson can tell a story that is a replay of the 2008 financial crisis in a different key, with different instruments, and a different ending – spoiler coming! – the banks get nationalized. And the book ends. He doesn’t tell us what happens next.

If the seas rise catastrophically, will the resulting world be a livable one? That’s the question Robinson asked in New York 2140. The seas have risen 50 feet in two major “pulses” (that have taken place before the story begins). There have been technological advances, but no space travel (none is depicted in the book), and no human-level artificial intelligence. But the basic political and economic structure of the world appears to be the same as our current world, hence Robinson can tell a story that is a replay of the 2008 financial crisis in a different key, with different instruments, and a different ending – spoiler coming! – the banks get nationalized. And the book ends. He doesn’t tell us what happens next.

That’s only New York City. What was happening in Kisangani, Bagdad, New Delhi, Sao Paulo, Lima, Kyoto, Hanoi, Guangzhou, St. Petersburg, and Prague? There seems to be plenty of room in that world for seasteading and charter cities. Assume lots of them. Could they plausibly give rise to a revolutionary restructuring of the world order?

We are free to imagine that, to write those stories.

Beyond the Chrysalis: Toward a Ministry for the Future

I am not of course, arguing that that IS how the future will unfold. Nor am I even suggesting we steer in that direction. I offer it simply as a device to think with, a tool for exploration and, yes, fun and adventure.

That’s what fans do, go adventuring in their favorite worlds.

Fan fiction abounds, film and video as well. I don’t know whether or not Kim Stanley Robinson has inspired others to tell their own stories in his worlds. But fans have dancing around in Star Trek and Star Wars for decades.

Forms of future-facing fiction have become standard in real-world thinking as well. Consider Futures Studies, sometimes traced back to H.G. Wells, and scenario planning, associated with military war gaming and developed for business planning by Royal Dutch Shell and others.

How then do we emerge from the Chrysalis of Decadence? We use science fiction to explore the far future – say, 40-50 years out. We synthesis knowledge across a wide variety of disciplines, academic and practical, to understand what has happened in the past and to assess the current situation. We then generate near-term scenarios to explore the space between the present and the far future. By examining those scenarios we can identify the treatment opportunities Collison and Cowan called for in “We Need a Science of Progress.”

Let us return to Kim Stanley Robinson. He has a new novel coming out in the fall, The Ministry for the Future:

“In The Ministry for the Future I tried to describe the next thirty years going as well as I could believe it might happen, given where we are now,” Robinson told Newsweek. “That made it one of the blackest utopias ever written, I suppose, because it seems inevitable that we are in for an era of comprehensive and chaotic change.”

Note, though, that he does call it a utopia.

Here’s what I’m thinking: Many schools have a Model United Nations program. What would a model Ministry of the Future Program look like? And I don’t mean 10 years from now when the real thing is up and running (Robinson imagines it for 2025), I mean right now as part of an effort to bring the real thing into existence. How would it relate to the current Progress Studies for Young Scholars program? I know, a working Ministry of the Future is a long way from tens, hundreds, and thousands of imaginative high school students interacting and dreaming over the internet about the future. But we have to start somewhere.

They have to start somewhere. They are the ones who will live with and execute programs we initiate now. We owe them the best tools we can craft.

Appendix 1: Progress Studies Online

Here’s the article that kicked things off

Patrick Collison and Tyler Cowen, “We Need a New Science of Progress”, The Atlantic, July 30, 2019.

Collison has collected some of the responses here.

Lots of people are interested in progress. Here are a few sites that resonate with this nascent movement:

- Roots of Progress: Jason Crawford has been blogging about the roots of progress since March 2017, and has been working on Progress Studies full-time, aided in part by a November grant from Cowen’s Emergent Ventures fund.

- Progress Studies for Young Scholars: While Jason’s continued blogging he’s also been organizing and has put together an online summer program in the history of technology aimed at high school students. Video lectures and interviews are available on YouTube.

- Progress Studies Slack: Started by Jasmine Wang, who also maintains a database of people interested in Progress Studies.

- Twitter: A number of people have been tagging Twitter messages with #HumanProgress.

Crawford recently gave an overview of the current state of the emerging progress studies movement:

The scope of the discussion:

- Progress Studies, as called for by Collison and Cowen, is about the organization, creation, and dissemination of scholarly research on progress. It calls on a wide range of investigation in the social and behavioral sciences, history, and the humanities.

- However, Progress Studies also has a practical focus. Thus we need a dedicated journal, a general interest magazine, think tanks, and institutionalized sources of funding (foundations).

- Progress Studies encompasses social and cultural factors as well as technology.

- Progress Studies is a long-term effort, requiring decades.

- Progress Studies is not politically partisan and has participants with a variety of ideological commitments.

Note that last point, that Progress Studies does not seem to be particularly partisan. That’s important. It is quite possible that the long-term possibilities for success in America depends on it as partisan politics seems dangerously deadlocked.

* * * * *

A Conversation with Mark Zuckerberg, Patrick Collison and Tyler Cowen

Transcript of the conversation (PDF).

Appendix 2: Douthat on Decadence

Robert Wright and Ross Douthat:

Douthat with Peter Robinson of the Hoover Institution:

[1] I can offer no citation for this, though there must be something out there. I know it because that NASA officials told us at the beginning of a 10-week program in the summer of 1981. NASA had brought us together to explore the potential of using artificial intelligence to revitalize NASA’s mission. I tell that story in a post, Summer 1981, When I advised NASA on their computing infrastructure.