by Rafaël Newman

A friend of mine, a retired Swiss high school teacher and an aficionado of American culture, has been compiling a list of “Pseudo Anglicisms”, words of evident English origin used in contemporary colloquial German (especially in Switzerland) which often have no actual correspondence in English as commonly employed by native speakers. His list includes Beamer (meaning a digital film projector and not the German automotive brand), Oldtimer (a vintage car and not a human veteran), Body (an undergarment), Handy (a cell phone), Mobbing (on-the-job harassment) and Talkmaster (an emcee), among many others. The database is currently being enhanced by his colleagues, who have recently proposed anomalies like Shootingstar (up-and-coming talent) and Tumbler (a clothes dryer).

Such borrowing from English is, unsurprisingly, particularly prevalent in the German-speaking business world, where Top Managers attend Trainings to be enriched by Learnings, receive Feedbacks and lament Pain Points at Briefings, and – last but not least, a peroration favored among Swiss rhetoricians – determine their company’s Purpose by Brainstorming to prepare themselves for an upcoming Challenge. This last term – Challenge – is ubiquitous in Helvetian business, advertising, and sports, driven in part by a spate of wacky fundraising dares on social media in the past years, and encouraged perhaps by the fact that the perfectly good native German equivalent – Herausforderung – is a less than sexy mouthful.

A new coinage has recently swelled the ranks of these ersatz Gastarbeiter, for obvious reasons: Home Office, what Anglophones typically call “remote working” or “working from home”, since the utterly sensible Germanic collocation has long been appropriated by a certain venerable British political institution. Home Office had of course already existed among Teutonic wage-earners as a voluntary labor arrangement, albeit requiring Human Resources approval, before it was actively imposed on thousands of employees in the German-speaking work world this spring, as elsewhere, for reasons of hygiene amid the slow-motion disaster of a novel virus. Now, as companies here in Switzerland begin to “open up” again, the measure, resented by some for depriving jobs of their sometimes single benefit of collegiality, is reverting to its more gratifying status as an optional feature of modern flextime employment contracts. (It should be noted that those who have since March suffered nothing worse than domestic Wi-Fi overload and struggles for the dining room table as their eminent domain may count themselves lucky, since many other thousands of Swiss employees – those who have not found themselves without a job altogether – have been subjected to Kurzarbeit or mandatory short-time working, with curtailed wages subsidized by the government: a measure for which there is, significantly, no glamorous, awkwardly imported English moniker.)

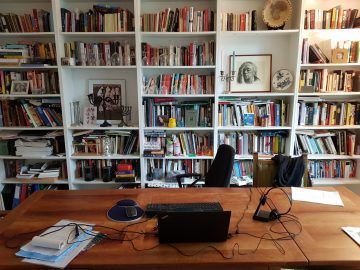

The organization I work for has made a virtue of necessity and created an online parlor game based on this temporary staff arrangement. Dubbed the Home Office Challenge, an entirely “English” name for an utterly Swiss diversion, it features daily posting on the company intranet of a photograph of an unoccupied domestic working space, with a list of three names of employees below it and an invitation to click on the one whose Home Office space is shown. (The thrill of the game, and its paradoxical “Swissness”, derives from the fact that the Swiss are in fact ordinarily quite jealous of their privacy and unwilling to reveal their domestic situation: hence their telling use of the “Pseudo Anglicism” Home Story for a media exposé of the private life of a celebrity.) In the Home Office Challenge, sometimes one or two or even all of the names are familiar, and thus the interior depicted might contain a clue to its occupant; more often than not, however (and virtually always in my case, as I have only worked at the organization since New Year’s), the names are all of unknown colleagues, and the game becomes more rudimentary, taking advantage of primitive prejudices: Does this look like a space arranged by a woman or a man? Would a person with a Latinate name be likely to feel comfortable here, or does its Gemütlichkeit betray a Germanic disposition? And, with hierarchical information gleaned from the online organizational chart: Are these the furnishings of an executive, or of a support worker?

Some of the Home Office spaces shown are elaborate, featuring ormolu knickknacks on exhibit beyond Second Empire desks; others are more austere, with an end table pushed into an ignominious corner, the only adornment visible a wall calendar. Some images, centred on twin screens ablaze with graphs, suggest exclusive focus on work, while others prominently feature a chunky Ikea junior desk and chair next to the grownup working-space, as if to stress simultaneous involvement in childcare. Other occupants provide Mitteleuropäisch earnest of their good humor in mock “Ye Olde Time” samplers emblazoned with jocular desiderata.

Each picture uploaded was taken, almost certainly, with the occupant’s cell phone, which is always to hand these days, in spite of – or indeed precisely because of – the Skype for Business equipment laid on at the employee’s home, equipment whose functioning is crucial to operations and thus necessitates a second means of communication with IT services given the periodic outages caused by unusual strain on the company network. The cell phone, of course, has restructured our reality in many ways, both profane and sublime, none more so perhaps than by simply transforming telephonic communication from a locational to a personal phenomenon: for whereas the standard question on a landline has traditionally been Who is speaking?, on mobile devices we are now far more likely to ask Where are you? In other words, in the past we summoned a place; now we interpellate a subject. We knew then where we were calling, but not whom; now we address our phone calls to a particular person in an unidentified location. The images on my company intranet replace this newfound personal certainty with the old locational knowledge: when I call up the day’s Home Office Challenge, I find that I have reached, once again, a certain place, and must determine the identity of its occupant.

These portraits of empty interior scenes – anti-selfies, in a sense, since their focus is by necessity on all of the details that ordinarily serve merely to frame or flatter the auto-photographer’s physiognomy – are invested with an oddly numinous nervous energy, a tension of expectation. As with shrines or cenotaphs, their power is derived from the invisible god, saint, or martyr they commemorate, whose absence paradoxically guarantees their authenticity and affords the devotee a pleasant frisson: What if the venerated spirit were suddenly to manifest itself? What if it were displeased with our worship, indeed with our mere, profane presence? What if (as a friend once wondered of an actual shrine, equipped with an effigy of the celebrated martyr) the seated statue of Lincoln were to suddenly rise from its chair? It would blow the roof off the Memorial.

The feeling the Home Office Challenge evokes, at least in this particular participant – the sense of familiarity mingled with strangeness, of pleasant recognition tinged with an unnamable dread – is what in German is known as das Unheimliche, or “the uncanny”; what the French call, with aptly redundant pedantry, l’inquiétante étrangeté: “unsettling strangeness”, a specific case of oddly arousing unfamiliarity. In his celebrated 1919 study of the phenomenon in art and lived experience, Sigmund Freud is alert to the unsettling strangeness inherent in the very term unheimlich – “un-home-ly” –in which the negative prefix is the sign of repression, distancing the experiencer from the resurgence of a troubling memory, one which presents itself as foreign but is in fact all too domestic: the “home-ly” or familiar is thus rendered strange by the simple expedient of denial, for all that it persists in barely concealed form. (The same operation is evident in the English “uncanny”, in which the “canny” – the wise, shrewd, or cunning – is disavowed, and assigned to the realm of the supernatural or metaphysical, even as it continues to raise hackles.) For Freud, of course, the Heim or “home” invoked by the sublated term heimlich (which also means “secret”) is the ancient site of infant impulse, of now-taboo aggressions, fears, and pre-sexual incestuous and parricidal desires, long since buried beneath the ash of the individual’s eruption into adult consciousness. For Freud, the “un” heralds the return of the repressed, which arrives in the unlikely garb of a chance encounter or everyday occurrence and arouses the ghostly feeling of das Unheimliche – the uncanny – which is somewhere between a senior moment and a déjà vu.

With the Home Office Challenge, what returns, while not repressed, has certainly been transformed, indeed estranged: for the subject of each photograph is the literal “home” named in the Pseudo Anglicism of the moment, now seen in the process of metamorphosis into its opposite, the office. That denatured home is here issued as a “challenge” in a memory game reminiscent of the mnemonic technique described by the Roman rhetoricians Cicero and Quintilian, which uses imagines (images) associated with loci (places) to recall the order of items in a speech and is said to derive from the method deployed by the Greek poet Simonides to identify the victims of a disaster.

This week, as the organization I work for gradually returns its employees to work on premises, the Home Office Challenge will presumably begin to wither away from the intranet. There is some debate about the details of the prophylactic measures to be observed – in particular, whether the distance obligatory between co-workers is two metres or just a metre and a half (the joke is that the Swiss will be relieved to see the two-metre rule lifted, since they have been longing to revert to their customary three-metre distance from one another) – and there have been ominous signals from the statistics on reinfection rates issued by the Health Department; but for the time being my colleagues and I are to be reinstated in our proper vocational sites, while our domestic environments are restored to their former status: private, unseen, secret, known only to a select circle. What will persist, however, like the vestiges of one’s own language embedded in a foreign discourse, is an uncanny familiarity, as the name of a colleague newly encountered in a public space revives the memory of a private interior, and the image of its once estranged occupant is now reunited with a newly familiar location, in a tentative reconstruction of the disaster we are all still living through.