by Mike O’Brien

Thirteen months of living under the spectre of plague has me looking for some means of escape. Mental escape, of course. Physically, I’m still stuck at home, abiding by various lockdown measures, awaiting with weary disdain my province’s next randomized adjustments to its infection-control scheme. Trapped below decks on a ship piloted by imbeciles, who believe that the sea respects economic imperatives and rewards prior restraint. It could be worse, of course. But that’s cold comfort as I anticipate the months of uncertainty between today and whenever I’m vaccinated.

My usual escape is to dive into curious corners of science and theory, learning odd bits of information about nature, or mechanics, or, if I’m feeling very adventurous, some dumbed-down version of maths. A recent dive led me into the world of astrobiology, a field rife with the kind of barely-tethered speculation that philosophers like myself thrive in. There are all kinds of empirical and technical questions, like what kinds of life used to exist on Earth when its chemistry was wildly different, and what kinds of chemical precursors are required to produce the elements necessary to terrestrial life. There are also more abstract questions about the probability of life’s emergence, and the probability that other advanced species exist given our inability to detect them. Even more removed from concrete facts are the ethical questions of what ought to be done and what does it all mean, and these are the easiest to write about without doing expensive experiments or troublesome equations, so I’m doing that. Read more »

In 1887 Ludwik Zamenhof, a Polish ophthalmologist and amateur linguist, published in Warsaw a small volume entitled Unua Libro. Its aim was to introduce his newly invented language, in which ‘Unua Libro’ means ‘First Book.’ Zamenhof used the pseudonym ‘Doktor Esperanto’ and the language took its name from this word, which means ‘one who hopes.’ The picture shows Zamenhof (front row) at the First International Esperanto Congress in Boulogne in 1905.

In 1887 Ludwik Zamenhof, a Polish ophthalmologist and amateur linguist, published in Warsaw a small volume entitled Unua Libro. Its aim was to introduce his newly invented language, in which ‘Unua Libro’ means ‘First Book.’ Zamenhof used the pseudonym ‘Doktor Esperanto’ and the language took its name from this word, which means ‘one who hopes.’ The picture shows Zamenhof (front row) at the First International Esperanto Congress in Boulogne in 1905.

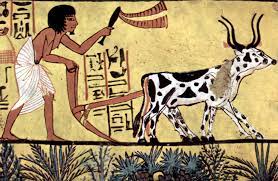

If, for a long time now, you’ve been getting up early in the morning, setting off to school or your workplace, getting there at the required time, spending the day performing your assigned tasks (with a few scheduled breaks), going home at the pre-ordained time, spending a few hours doing other things before bedtime, then getting up the next morning to go through the same routine, and doing this most days of the week, most weeks of the year, most years of your life, then the working life in its modern form is likely to seem quite natural. But a little knowledge of history or anthropology suffices to prove that it ain’t necessarily so.

If, for a long time now, you’ve been getting up early in the morning, setting off to school or your workplace, getting there at the required time, spending the day performing your assigned tasks (with a few scheduled breaks), going home at the pre-ordained time, spending a few hours doing other things before bedtime, then getting up the next morning to go through the same routine, and doing this most days of the week, most weeks of the year, most years of your life, then the working life in its modern form is likely to seem quite natural. But a little knowledge of history or anthropology suffices to prove that it ain’t necessarily so. It’s official: Lilly Singh, the YouTube phenomenon,

It’s official: Lilly Singh, the YouTube phenomenon,

Marlène Huissoud. A3 Drawings 8, 2020.

Marlène Huissoud. A3 Drawings 8, 2020.

Patriotism is a contested ideal in the culture war which bubbles away in the UK. It’s worth examining not only as an idea in itself but also with regards to how it is understood and expressed in the present cultural context of the UK. It seems to me that the debate is dominated by two ends of a spectrum, both misguided. At one end there are those who find the word itself too problematic to be worth salvaging. It is, they would argue, despite claims to the contrary, unavoidably linked to its ugly cousin, nationalism, with its xenophobic and jingoist associations.

Patriotism is a contested ideal in the culture war which bubbles away in the UK. It’s worth examining not only as an idea in itself but also with regards to how it is understood and expressed in the present cultural context of the UK. It seems to me that the debate is dominated by two ends of a spectrum, both misguided. At one end there are those who find the word itself too problematic to be worth salvaging. It is, they would argue, despite claims to the contrary, unavoidably linked to its ugly cousin, nationalism, with its xenophobic and jingoist associations.

Copse and cosmos

Copse and cosmos

“My first experience home-brewing was before it was legal,” says Jim Koch, cofounder and chairman of Boston Beer Company, maker of Sam Adams. “I did it with my dad. He brought home some yeast … then he brought home some hops, and we made a beer. And I thought it was so cool when the yeast brought the beer to life, and it started to bubble and you got that foam on the top of it, and it had that wonderful bready, ester-y smell, and I was in love.”

“My first experience home-brewing was before it was legal,” says Jim Koch, cofounder and chairman of Boston Beer Company, maker of Sam Adams. “I did it with my dad. He brought home some yeast … then he brought home some hops, and we made a beer. And I thought it was so cool when the yeast brought the beer to life, and it started to bubble and you got that foam on the top of it, and it had that wonderful bready, ester-y smell, and I was in love.” The evidence that pairing music with wine can enhance one’s tasting experience continues to mount since

The evidence that pairing music with wine can enhance one’s tasting experience continues to mount since