Black vultures in the parking lot of the building next to my hotel in Houston, Texas, last week.

Category: Monday Magazine

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

A Review of Sue Hubbard’s Fourth Poetry Collection: Swimming to Albania

by Maniza Naqvi I find Sue Hubbard’s writings to be an invitation to feel sorrowful. And therefore a beckoning towards a search for beauty, an attempt at forgiveness and redemption and reckoning; a belief in the possibility of joy.

I find Sue Hubbard’s writings to be an invitation to feel sorrowful. And therefore a beckoning towards a search for beauty, an attempt at forgiveness and redemption and reckoning; a belief in the possibility of joy.

Swimming to Albania, Sue Hubbard most recent and fourth collection of poem’s reveals once again, the poet’s third and internal eye, which searches and sifts through cold water and cinder to find the source and alchemy, the gift to distill it all into words which reach right into her own and perhaps the reader’s soul. Her gift is to reach through her poems to possibilities and safe shores—where the view collapses all three, past, present and future; to the point that hope, sorrow, grief and memory—-become one. Through this, past it and to it, it becomes deeply comforting. And this merging into one, is a balm as soothing as swimming, helping us to understand that we go on and on—in memory—and this then, this now is the future. Read more »

Charaiveti: Journey From India To The Two Cambridges And Berkeley And Beyond, Part 43

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

June 4 early morning we took a taxi from Friendship Hotel to the Beijing airport, oblivious of the dreadful happenings in Tiananmen Square the previous night. I remember the taxi driver in his almost non-existent English tried to tell us that ‘something’ (he was not sure what) had happened in the night in the Square, traffic was not allowed to go in that direction. By the time we reached Shanghai, our hosts who came to receive us knew. Of course, they could not know it from radio or TV, as there was a news blackout. These were days before internet, but cross-country fax messages were still active. Beijing to Shanghai messages were blocked, but people in Beijing were sending fax messages to their friends and relatives in Los Angeles, and the latter were sending messages to Shanghai.

June 4 early morning we took a taxi from Friendship Hotel to the Beijing airport, oblivious of the dreadful happenings in Tiananmen Square the previous night. I remember the taxi driver in his almost non-existent English tried to tell us that ‘something’ (he was not sure what) had happened in the night in the Square, traffic was not allowed to go in that direction. By the time we reached Shanghai, our hosts who came to receive us knew. Of course, they could not know it from radio or TV, as there was a news blackout. These were days before internet, but cross-country fax messages were still active. Beijing to Shanghai messages were blocked, but people in Beijing were sending fax messages to their friends and relatives in Los Angeles, and the latter were sending messages to Shanghai.

We were put up in the faculty guest house of Fudan University. It turned out that our living room in the guest house had the only short-wave radio in the whole campus. So for the next few days endless streams of students and young faculty came to our room to listen to the news on BBC or Voice of America. Even though we had to listen to the same grim news again and again, this gave me an opportunity to talk to many young people in the campus. Along with discussing the news, I also asked them about their life, their studies, their family backgrounds and so on. In response to my question about what they’d like to do after university, in general the ones who were more forthcoming or whose English was better would usually say that they’d like to work for a ‘joint venture’ (joint between a Chinese company and a foreign multi-national company). I noticed that these students had often adopted English first names like Max or Susan to introduce themselves, I presume just to make things easier for the foreigners–I think the same was probably true for Justin Lin in Beijing. (In recent years I have noticed a big change in the reverse direction: my friends in China who used to send me email earlier with their Chinese names in Romanized letters, now almost always use only Chinese characters. So when I receive an email from China it takes a bit of time for me to know who the email is from, without reading the text of the message which is mercifully still in English). Read more »

Monday, May 2, 2022

If There Were a Vaccine Against Love, You Should Take It

by Thomas R. Wells

The argument in brief:

1. Romantic love hijacks our desires and practical reasoning

2. If your desires and practical reasoning are hijacked your decisions aren’t authentically your own

3. If there were something that would prevent you from falling in love (a ‘vaccine’), it would prevent this hijacking

Therefore,

4. If there were a vaccine against romantic love, you should take it

I. The Case Against Romantic Love

First, I do not deny that being in romantic love feels great. But I do deny that this answers the question of whether being in love is a good thing. After all, heroin feels great, but that doesn’t make it good for us.

Romantic love – and note that I am talking throughout about the crazy euphoric kind of love here, not the boring companionable kind – is exactly like being on drugs because it is. It operates by hijacking our emotions, desires, and practical reasoning at the neurochemical level by manipulating our dopamine and endorphin systems (valuation and pleasure). Love is a cognitive distortion field that makes us gloss over particular people’s flaws and want to refocus our lives around them. The term ‘endorphin’ is short for endogenous morphine. It binds to the same opiate receptors as heroin. We suffer literal drug withdrawal symptoms when separated from the object of our love. Read more »

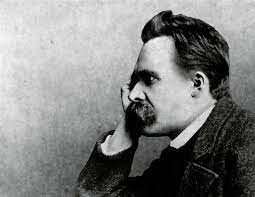

Why Nietzsche is my desert island philosopher

by Emrys Westacott

Friedrich Nietzsche is my “desert island philosopher.” Guests, or “castaways” on BBC Radio 4’s long running program “Desert Island Discs” are allowed to take to their desert island, in addition to eight pieces of music, a text of religious or philosophical significance. Many accept the bible as the default option. For me, the choice is a no brainer: I’d take the works of Nietzsche.

Friedrich Nietzsche is my “desert island philosopher.” Guests, or “castaways” on BBC Radio 4’s long running program “Desert Island Discs” are allowed to take to their desert island, in addition to eight pieces of music, a text of religious or philosophical significance. Many accept the bible as the default option. For me, the choice is a no brainer: I’d take the works of Nietzsche.

But why? It certainly isn’t because he’s the thinker I agree with most. In fact there are many aspects of his thought that are silly, hopelessly outmoded, or morally objectionable. Some of his observations about women, about racial types, about democracy, and about liberal values in general, for instance, are about as misguided as its possible to be––at least from the standpoint of anyone who endorses said liberal values. His unabashed elitism, and occasional apparent indifference to the suffering so often inflicted on the many by the powerful few, would be almost laughable if it weren’t for the fact that we still live in a world were such suffering abounds.

Finding examples in Nietzsche’s writings of propositions that are awful-going-on-horrible is like looking for a needle in a tin of needles. On women, for instance:

When a woman has scholarly intentions there is usually something wrong with her sexually.[1]

On how the ruling class may and should treat those beneath them:

The essential characteristic of a good and healthy aristocracy …is that it experiences itself not as a function (whether of the monarchy or the commonwealth) but as their meaning and highest justification–that it therefore accepts with a good conscience the sacrifice of untold human beings who, for its sake, must be reduced and lowered to incomplete human beings, to slaves, to instruments.[2]

Or on what constitutes progress:

The magnitude of an “advance” can… be measured by the mass of things that had to be sacrificed to it; mankind in the mass sacrificed to the prosperity of a single stronger species of man–that would be an advance.[3]

Given such sentiments, why on earth do I like Nietzsche so much? After all, I like most of Nietzsche readers–and today he is probably the most popular of the “great” philosophers–would almost certainly be judged by him to be “herd” or “rabble,” self-interestedly promoting the values of what he calls “the last man”–viz. safety, comfort, contentment, and mediocrity. Read more »

Rite of Passage

by Raji Jayaraman and Gayatri Jayaraman*

Embarking on a road trip destined for a deserted strip of land on India’s southern coastline had never been on our radar. Neither had we imagined making such a trip in order to consecrate our mother’s ashes to the sea. After her death in September 2019, we had fully intended to do something but going through a religious ritual was not necessarily top of mind. For starters, neither of us is religious. Our brother is a proselytizing atheist and we are both agnostic, on optimistic days. Ironically enough our mother, though deeply religious, had not expressed a wish for rituals. A compulsive altruist till the bitter end, she had wanted to donate her body to science, but this option was not viable so her body was cremated instead. Then Covid intervened.

For two and a half years, our mother’s ashes sat in a box in Toronto. And during this time we attempted, with mixed success, to cope with the depth of our loss. Our mother was a force of nature, a remarkable woman. She was vivacious, filling each room she entered with her contagious laugh. She listened without judgment, she gave without expectation, she loved fully and unconditionally. True to her nature, she accepted her stage 4 ovarian cancer diagnosis with grace but tried to hold it at bay for as long as she could. Two years after her initial diagnosis she died peacefully, surrounded by her family. We cremated her body the next day. She didn’t want a public service and frankly, neither did we. The loss was too personal. We sent an obituary out to her friends and extended family and published a death announcement in a few Indian newspapers, but we didn’t hold a funeral. Read more »

Perceptions

What to Do with Pain

by Michael Abraham

Take a star of anise and a pinch of lavender in either hand. Hold these to the chest and whisper out a little prayer. Splash clean water on the face. Brush the teeth. Fret over little details in the bedroom, whether the paintings are hung straight, whether the posters are in the right places. Shift the vase so it catches the morning sunlight. Light a candle. Pray again. Take three deep breaths and press your palms together, hard, in the way your therapist taught you. Give up on this and smoke a cigarette instead. Feel the smoke as it passes your teeth and scratches your throat. Turn your body to face the wind. Take in the wind—the dirty, city wind—and pretend it is lovely. Put in your headphones and play “Mama Said” by The Shirelles. Mama said there’d be days like this, there’d be days like this, my mama said.

***

The moment you realize you’re in pain may not be the moment in which you begin to hurt. You may hurt for days, months, years before you ever notice. But the moment you notice is essential. It is the defining moment of this season of your life. The moment you notice you’re in pain, you suddenly have agency; you suddenly have choices to make. Staring up at the ceiling of this little room in Brooklyn where I live now, I realize I have been hurting for years. The knowledge of this descends upon me like a great weight, and then, in the next moment, the weight recedes like a wave is pulled back out to sea. The weight recedes, leaving only the knowledge, like beach foam, something weightless but apparent, obvious, easy to spot. The knowledge glitters in the sun. Consider the glitter, the cruelty of it, the obviousness. Pain is so obvious except for when it is so routine that it disappears from notice. But, eventually, sooner or later, like the wave foam, pain will come forward in the mind; irrepressibly, it will make itself known. Read more »

Language, Identity, and Pakistani Writing in English

by Claire Chambers

Language has an important role to play in national identity. One only has to think about the Shaheed Minar in Dhaka. As its name suggests, this monument commemorates what many Bangladeshis view as the shaheeds or martyrs of the Bengali language movement who were killed in Bengal in 1952. The history of West Pakistan’s linguistic imperialism contributed significantly to the 1971 War and the creation of Bangladesh out of Pakistan’s former East Wing.

Language has an important role to play in national identity. One only has to think about the Shaheed Minar in Dhaka. As its name suggests, this monument commemorates what many Bangladeshis view as the shaheeds or martyrs of the Bengali language movement who were killed in Bengal in 1952. The history of West Pakistan’s linguistic imperialism contributed significantly to the 1971 War and the creation of Bangladesh out of Pakistan’s former East Wing.

However, in the context of present-day Pakistan and the Indian subcontinent more broadly, the relationship between language and nation is a complex and contested question. The English language continues to exert a tenacious hold over the subcontinent. In the decades immediately before and after Partition, the majority of South Asians, especially leftists, rejected the use of English for creative purposes, positioning it as an elitist, colonial tongue. For instance, article 4 of the Manifesto of the Progressive Writers Association (1936), sets out the radical authors’ goal ‘to strive for the acceptance of a common language (Hindustani) and a common script (Indo-Roman) for India’. Tellingly, though, this manifesto was drafted in the Nanking Restaurant off Charing Cross Road in London, signalling the inescapable hold of the English language despite the group’s grassroots aims.

Far from making a political choice to write in English, many writers who were educated in the ‘English-medium’ system in Pakistan or Anglo-American countries up to the present have English as their strongest language. As a character in Aamer Hussein’s Another Gulmohar Tree remarks, ‘You don’t choose the language you write in, it chooses you’. The continuing power of English also arises because in the subcontinent there is no single language that has universal support. I do not forget the possible exception of Bangladesh already discussed, but even in that Bengali-dominant country, Urdu speakers are a beleaguered minority upsetting the linguistic equilibrium. Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Assertion and the Puzzle of Self-Actualizing Lies

by Joseph Shieber

Suppose that you were in charge of a large government agency responsible for dealing with public health emergencies. Suppose furthermore the country is in the midst of just such an emergency, and that there is a particular action that, if a large enough percentage of the public performs that action, will alleviate a significant amount of the ill-effects of the current public health emergency. Let’s say that the large enough percentage of participation is 70%. The action is one that requires ongoing participation: even if a member of the public is currently performing the action, they have to KEEP performing it in order for the benefits to accrue.

Suppose finally that your agency is the only agency with access to accurate information about the participation rate, and your tracking data suggests that the participation rate is at 50%. At a press conference, a reporter asks you a question about the current participation rate.

So far, this imagined example has none of the farfetched qualities that people associate with philosophical thought-experiments. Indeed, most of the example will involve the sorts of situations that could very plausibly emerge. However, there is one aspect of the example that WILL be fantastical, but not in a way that should affect our judgments about the questions that I want to raise – in fact, this aspect should just serve to sharpen those questions. Read more »

The Mind and the Quantum: Complementary Perspectives

by Jochen Szangolies

Reading the words ‘mind’ and ‘quantum’ in close proximity on the internet rarely inspires great confidence. Indeed, all too often, all this indicates is that you’re about a click away from learning about life-changing techniques of ‘Quantum Jumping’ to a parallel reality where all your wishes come true, using ‘Quantum Healing’ to ‘holistically’ heal the ‘bodymind’, and other What the Bleep Do We Know!?-esque nonsense. Therefore, in writing about the fraught intersection of quantum mechanics and the study of consciousness, one is faced first with the challenge of convincing the reader that there is actually something of value to be gained from investing their attentional resources. So let me first consider arguments against the relevance of quantum mechanics for consciousness.

First, of course, mere woo-by-association does not make a good argument. That people have misused the buzzwords of ‘quantum’, ‘mind’, ‘consciousness’ and the like to promote shoddy self-help strategies does not entail that they can’t be combined in a sensible, and ideally even illuminating, way. But there are commonly-cited objections that deserve serious consideration.

The most common is the ‘large, warm, and wet’-argument. Quantum mechanics is often (if somewhat misleadingly) considered to be the ‘science of the small’, whose effects are typically observed at length scales far removed from everyday sizes, and thus, from brains. Furthermore, quantum effects typically requires systems to be well-isolated from the environment, to not fall prey to decoherence effects. But brains aren’t generally thus isolated—indeed, in a sense, it’s the very point of a brain to interact with the environment. Finally, quantum systems, to limit interaction, often have to be cooled down to a few degrees above absolute zero, something that again isn’t conducive to the proper functioning of a brain. Read more »

Writing about Music

by Derek Neal

I’m not sure anyone has ever figured out how to write about music. This is a dangerous statement to make, and I’m sure readers will be quick to point out writers who have been able to capture something as intangible as sound via the written word. This would be a happy result of this article, and I welcome any and all suggestions. I should also say that I don’t mean there are no good music writers; there are, and I have certain writers I follow and read. But the question of how to write about music remains a tricky one.

I’m not sure anyone has ever figured out how to write about music. This is a dangerous statement to make, and I’m sure readers will be quick to point out writers who have been able to capture something as intangible as sound via the written word. This would be a happy result of this article, and I welcome any and all suggestions. I should also say that I don’t mean there are no good music writers; there are, and I have certain writers I follow and read. But the question of how to write about music remains a tricky one.

As far as I can tell, most writing about music is built on analogies and cliches. This is understandable; you can’t describe music literally because it wouldn’t give an accurate representation of what it is you’re hearing. What use is it to say that a song is written in the key of A minor, has a tempo of 110 beats per minute, and follows a 4/4 time signature? These facts don’t add up to much. On the other hand, using analogies to describe music is meant, I suppose, not to state the objective facts of a song but to capture the experience of listening to a song and the subjective emotional response created within the listener. Perhaps, in combining technical, factual description of a song with figurative language, a song can be captured via text and the reader can hear the song in their head without ever actually having heard it out loud. This seems to be the goal of most music reviews.

I was put in mind of all this when I read an article in this month’s issue of Harper’s about the transition from the pre-internet world to the digital world of today. The author, Hari Kunzru, was writing about how he would read descriptions of music in magazines and try to imagine what the music sounded like, which does bring up the question: when we can listen to any song instantly, is it even necessary to attempt to put music into words? Perhaps the genre of the music review is simply a historical anomaly that has run its course. This may be true, but the same could be said and has been said for the novel, the essay, and many other forms of traditional composition. And yet here I am, writing these words, so I’ll continue to explore the description of music and attempt to achieve its goal of transmitting sound via written language. Read more »

Monday Photo

A Sputnik Education: Part 3

by Dick Edelstein

I got an incredible break when I was thirteen. We moved to Seattle and I entered public school in the sixth grade, after five years of Catholic education. The impact of the change in fortune was all the greater since I had no particular expectations, a good example of the principle that you can never know when things are about to change for the better. It was not just that my least favorite subject, religion, was no longer on the curriculum–that was the least of it. My new school exuded a different mood, much more open, so different to the reform school atmosphere I had become accustomed to. My life began to feel truly blessed.

I got an incredible break when I was thirteen. We moved to Seattle and I entered public school in the sixth grade, after five years of Catholic education. The impact of the change in fortune was all the greater since I had no particular expectations, a good example of the principle that you can never know when things are about to change for the better. It was not just that my least favorite subject, religion, was no longer on the curriculum–that was the least of it. My new school exuded a different mood, much more open, so different to the reform school atmosphere I had become accustomed to. My life began to feel truly blessed.

My first day in class was unforgettable. At the start of class, the teacher introduced me and asked if they could call me Dick. To my surprise, I answered in the affirmative even though I had always been called Richard. In a single haphazard stroke of unaccustomed boldness, I had named myself. My dad took it with a grain of salt and my mom was appalled.

There was more. The school year was already in progress and this was election day. Every month a new class president was elected. Owing solely to the fleeting popularity of being a new boy, I was elected. The other candidate had expected to win but took it with good grace. His name was Ike like the former US president. That very day he began to initiate me into his world. One of his chief interests was electronics. Since this field of knowledge was not covered in the curriculum at this early age, I was able to glean what I needed to know about it from magazines and the public library. Read more »

Charaiveti: Journey From India To The Two Cambridges And Berkeley And Beyond, Part 42

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

The interest of both Masahiko Aoki and Gérard Roland in institutional economics easily shaded into comparative analysis of economic systems, including different varieties of capitalism and socialism. Since my student days I have been acutely interested in comparative systems and their political economy. In this context like Aoki and Roland I have closely followed developments in China. When I was growing up in Kolkata the leftists around me used to say that the Chinese were better socialists than us, now in the last three decades I have heard in all quarters that the Chinese are better capitalists than us. To reconcile the two I sometimes tell people that if the Chinese are better capitalists now this is partly because they were better socialists then. This is not an entirely flippant comment. By the end of the Mao regime in middle 1970’s, before Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms started, Chinese performance indicators in basic health, education and rural electrification showed levels unattained by India even by two decades later. This gave China a head start in providing the basis of capitalist industrialization.

The interest of both Masahiko Aoki and Gérard Roland in institutional economics easily shaded into comparative analysis of economic systems, including different varieties of capitalism and socialism. Since my student days I have been acutely interested in comparative systems and their political economy. In this context like Aoki and Roland I have closely followed developments in China. When I was growing up in Kolkata the leftists around me used to say that the Chinese were better socialists than us, now in the last three decades I have heard in all quarters that the Chinese are better capitalists than us. To reconcile the two I sometimes tell people that if the Chinese are better capitalists now this is partly because they were better socialists then. This is not an entirely flippant comment. By the end of the Mao regime in middle 1970’s, before Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms started, Chinese performance indicators in basic health, education and rural electrification showed levels unattained by India even by two decades later. This gave China a head start in providing the basis of capitalist industrialization.

The two largest countries of the world with ancient agrarian civilizations, with many centuries of dominance in the world economy in the past (up to about 1800) and with impressive economic growth achievements in recent decades though with different political and economic systems, draw obvious comparison, but since 1990 the Chinese economic performance has been far superior. My first piece of comparative study of Chinese and Indian agriculture came out in the Journal of Asian Studies in 1970. Fifty years later, I was still at it, with my piece on a comparison of the economic governance systems of the two countries coming out in China Economic Review in 2020. Meanwhile in 2011 I published a book titled Awakening Giants, Feet of Clay: Assessing the Economic Rise of China and India. One abiding theme in my recent work has been that China-India comparison is not a simple matter of authoritarianism vs. democracy. While there are some undoubtedly positive features of the Chinese governance system, authoritarianism is neither necessary nor sufficient for those features. On the other hand, there are some ugly features of the Chinese system that are inherent in authoritarianism. Read more »

Monday, April 25, 2022

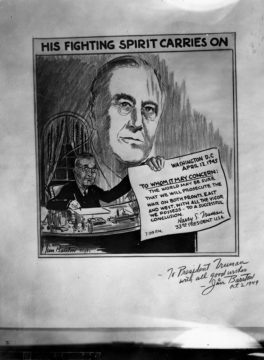

Last Person Standing: The Presidential Succession Act Turns 75

by Michael Liss

I have a terrific pain in the back of my head.

—Franklin Delano Roosevelt, April 12, 1945.

It was all so fast. Just moments earlier, FDR was sitting for an official portrait, reading the newspapers, writing a few notes. Now, after 12 years of turmoil, World War and Depression, he is gone, work unfinished. Within hours, his successor, Harry S. Truman, is sworn in, and, for the first time, is told of the Manhattan Project. The awesome moral responsibility for the use of nuclear weapons falls on his shoulders, and a bullseye appears on his back.

The fact is that Vice Presidents are pretty much non-entities, supporting actors in a one-man play, unless and until they suddenly become the most important person in the world. History shows us that this occurs far more often than simple mortality tables might suggest. By one estimate, being President is about 27 times more dangerous than being a lumberjack.

The authors of the Constitution understood this, but, after vigorously debating the extent of Executive Power and the interrelationship of the three branches of government, and creating the future monster known as the Electoral College, they flickered out a bit when it came to figuring out Presidential succession beyond the elevation of the VP. Instead, they kicked the can to Congress in Article II, Section 1, Clause 6, to declare which “Officer” would act as President if both the President and Vice President died or were otherwise unavailable to serve during their terms of office “until the disability be removed, or a President shall be elected.” Read more »

This Is Not The Zombie Apocalypse

[This is the eighteenth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

Early in the story of The Walking Dead — the enormously popular, post-apocalyptic, television series — sharpshooting everyman, Rick Grimes, finds himself cast as leader to a group of beleaguered survivors, who must navigate the malignant chaos of a world suddenly overtaken by zombies. Every comfort, convenience, and civic structure of modern American life has collapsed. The threat of death lurks beyond every hillock or behind any tree. Ordinary people are left to fend for themselves against overwhelming forces, with nothing but guns (and the odd pickaxe or crossbow) for aid. And sentimental attachments to other people only leave individuals more vulnerable to attack. In this world that has slipped the grip of civilization, Grimes works to keep a strain of justice and mercy aloft within his desperate band.

Early in the story of The Walking Dead — the enormously popular, post-apocalyptic, television series — sharpshooting everyman, Rick Grimes, finds himself cast as leader to a group of beleaguered survivors, who must navigate the malignant chaos of a world suddenly overtaken by zombies. Every comfort, convenience, and civic structure of modern American life has collapsed. The threat of death lurks beyond every hillock or behind any tree. Ordinary people are left to fend for themselves against overwhelming forces, with nothing but guns (and the odd pickaxe or crossbow) for aid. And sentimental attachments to other people only leave individuals more vulnerable to attack. In this world that has slipped the grip of civilization, Grimes works to keep a strain of justice and mercy aloft within his desperate band.

But torn away from the cogency of his ordinary, 21st-century life, and cast into unrelenting danger and uncertainty, even Grimes’s kinder impulses are slowly ground away by his unabating experiences of horror and loss. His moral compass spins erratically. By the fifth season of The Walking Dead, the line separating Grimes from the threats he’s fought for years to hold at bay has worn distressingly thin. In fact, much before this, the show’s storylines and characters have already notably shifted their attention from the horrors of the zombies to the horrors of relying upon one’s fellow dislocated human beings for refuge and assistance in an ongoing crisis. Confronting the atrocities committed by the living profoundly changes Grimes and every member of his crew, as they also become more adept killers. Yet, uncannily, the social world they inhabit together doesn’t change much at all.1 Read more »

Monday Poem

War & Weekends

I’m writing from a list of prompts

in an exercise for loosening the tight grip

of uncertainty of mind in an effort

to knock the chocks from under its

big wheels to let the thing roll

yesterday’s was war, which I skipped,

never having been there but in books

and other vicarious means, safe

for the time being in my bubble—

yet there it is today, in news, on screen, its horror,

its devastation, its grief, its incendiary reality,

its cyclical road to nowhere

lined with corpses —immediate.

but today the prompt is: weekends,

two days arbitrarily set aside

as if they were, literally, the end of weeks

which themselves are inventions,

yet we love them so, respite as they are

from the famous dictum of Eden

at the moment of our eviction that: we

shall, henceforth, labor by sweat of brow

—at least until robots are conceived

further down the road and AI comes along

to relieve us from the ache of work

and thought, and knowing— and,

we shall sweat in sorrow, no less—

which brings us back to war and other

misapprehensions and monkey-wrenches

of thought and mind concocted by beings

who wage war and write poems

.Jim Culleny, 4/23/22

Scientific Models and Individual Experience

by David Kordahl

I’ll start this column with an over-generalization. Speaking roughly, scientific models can be classed into two categories: mechanical models, and actuarial models. Engineers and physical scientists tend to favor mechanical models, where the root causes of various effects are specified by their formalism. Predictable inputs, in such models, lead to predictable outputs. Biologists and social scientists, on the other hand, tend to favor actuarial models, which can move from measurements to inferences without positing secret causes along the way. By calling these latter models “actuarial,” I’m encouraging readers to think of the tabulations of insurance analysts, who have learned to appreciate that individuals may be unpredictable, even as they follow predictable patterns in the aggregate.

Operationally, these categories refer to different scientific practices. What I’ve called a difference between mechanical vs. actuarial models could just as well be sketched as a difference between theory-driven vs. data-driven models. Both strains have coexisted in science for the past few centuries.

Just for fun, we might attempt to caricature the history of modern science in the mechanical vs. actuarial terms introduced above. In the seventeenth century, Isaac Newton proposed a law of universal gravitation, applicable everywhere throughout the universe, which allowed naturalists to imagine that all physical effects, everywhere and for all time, were caused by physical laws, just waiting to be discovered. This view was developed to its philosophical extreme in the eighteenth century by the French mathematician, Pierre Laplace, who imagined that the universe at any particular moment implicitly contained the specifications for its entire past and future.

But in the nineteenth century, Charles Darwin introduced his theory of natural selection, which allowed naturalists to take actuarial models more seriously. Just as hidden order could cause the appearance of randomness, hidden randomness could cause the appearance of order. Read more »

Leandro Erlich. “BÂTIMENT”, 2004, La Nuit Blanche, Paris, France.

Leandro Erlich. “BÂTIMENT”, 2004, La Nuit Blanche, Paris, France.