by Thomas O’Dwyer

1066 And All That, a sly rewrite of the history of England, was published in 1930 and became a perennial bestseller. Its subtitle was A Memorable History of England, Comprising All the Parts You Can Remember, Including 103 Good Things, 5 Bad Kings and 2 Genuine Dates. Written by W. C. Sellar and R. J. Yeatman, the book, in the words of one critic, “punctured the more bombastic claims of drum-and-trumpet narratives … both the Tory view of ‘great man’ history and the pieties of Liberal history.” There is no connection, literary or otherwise, between this satirical non-fiction and 2666, the weighty novel by Chilean author Roberto Bolaño, published after his death from liver failure in 2003 at the age of 50. However, that phrase “all the parts you can remember” triggered an association when I found a battered copy of Bolaño’s novel among some old books discarded on a park bench. But it was a half copy — the covers and last 100 pages of the 900-page tome were missing. “The parts you can remember” reminded me of my spotty knowledge of Latin American writing picked up in those faddy years following the so-called Boom in the region’s literature from the 1950s to the 1970s. In the English-reading world, any serious book-lover felt obliged to mention, at the drop of a dinner-party conversation, Jorge Luis Borges, Julio Cortázar, Gabriel García Márquez, Mario Vargas Llosa, Isabel Allende, Octavio Paz, or Carlos Fuentes. The ultimate one-upmanship would have been to claim reading one of the authors in Spanish, but in my years in England, I never heard anyone do so. “You don’t read Borges,” one friend mocked. “You read his translator. That’s like washing your feet with your socks on.”

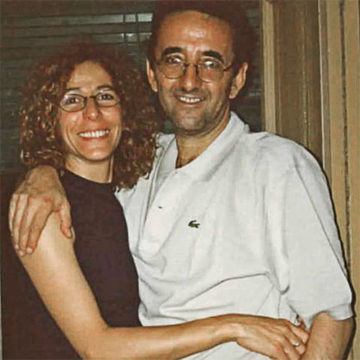

I do not, however, recall the name of Roberto Bolaño being bandied about, even though The New York Times later described him as “the most significant Latin American literary voice of his generation.” He was among the many Latin American writers, male and female, writing in Spanish and Portuguese who never made it into English-language reading lists or newspaper reviews, at least in Europe. Like other Latin American writers, he was perhaps more familiar to the general reading public in America because of its closer connections to the region. Born in 1953, Bolaño was an author outside the Boom period; he published his first novel, The Skating Rink, in 1993 but had always regarded himself as mainly a poet. Reinventing Love, a 20-page booklet of poems appeared in México in 1976. Later poetry publications included Fragments from the Unknown University, written between 1978-1992, and The Romantic Dogs, 1980-1998. Bolaño said in interviews that he only began writing novels because he couldn’t support his wife Carolina and two children as an impoverished poet.

When he died, the obituaries hailed him as a Spanish-language literary star, probably the most important Latin-American writer since Márquez. English readers were slower to grasp the reputation he had among Spanish readers. Translations of his novels and short stories emerged only after his death and in 2007 the translator Natasha Wimmer finally brought Bolaño to the Anglo world’s attention with The Savage Detectives, which he had published in Spanish in 1998. In 2005, The New Yorker began publishing Bolaño’s short stories and printed around a dozen over the following years. The Savage Detectives features a fictional poetic movement called visceral realism — a term often applied to Bolaño’s own style — founded in Mexico City in the mid-1970s. Bolaño lived in Mexico during this period and he helped start a disruptive literary group called infrarealistas. Until he married and settled in the village of Blanes in northern Spain in the early 1990s, he had been mostly vagrant. He supported his frequent moves with odd day jobs (dishwasher, bellhop, garbage collector) and writing poetry at night. He carried business cards with the legend, “Roberto Bolaño, Poet and Vagabond.”

The Savage Detectives is the best place to start reading this Chilean author in English since it introduces some leading themes in his work. Bolaño likes to explore the lives of writers, particularly poets. These are mainly impoverished and cast off from the literary establishment. They are vagabonds or hippies, usually with the manners of an organ grinder and the sexual morals of his monkey. Wimmer also translated 2666 and five other novels; another translator, Chris Andrews, produced six more in English. (I soon abandoned my disintegrating 2666 and bought a narrated edition on Audible to use on a daily walk). The English translation of Savage Detectives won high praise, but there was the bigger surprise to come.

For the last five years of his life, Bolaño immersed himself in a truly ambitious project, one he regarded as his masterwork — his Ulysses or War and Peace. This was 2666. He knew his days were closing in because of chronic liver disease (not alcohol-related). After his death, it was reported that he had just moved up to third place on a waiting list for a transplant. He did not finish the novel to his satisfaction and had started a final revision. “There are more than a thousand pages that I have to correct,” he told a Chilean newspaper a month before his death. “It’s a job for a 19th-century miner.” Bolaño left instructions that the five parts of 2666 be published separately for the financial advantage of his children. His literary executors send the unedited manuscript to the publishers, who accepted it and released it in 2004, ignoring his wish for a 5-volume series.

Yet there is merit in getting this novel as a whole giant work, like a Moby Dick, strange, marvellous, sad and funny, filled with humanity and horror. The book won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction in 2008, and translator Natasha Wimmer accepted the award in place of the deceased author. The Argentinian writer Rodrigo Frey wrote: “What is sought and achieved here the total novel, placing the author of 2666 on the same team as Cervantes, Stern, Melville, Proust and Pynchon. Like each of these titanic forebears, Bolaño has come close to reimagining the novel.” A review in the British Independent on Sunday said: “2666 has the power to mesmerise … All human life is in these burning pages, and Natasha Wimmer deserves a medal for her fluent translation.”

Bolaño never explained the title of the novel. It falsely hints at a science-fiction theme, and the number 2666 appears nowhere in the book. The English translation runs to 900 pages, and the work is in five parts. The mystery title has prompted some guesswork among reviewers and fans of the author. Some suggest a reference to the biblical Jewish Exodus from Egypt 2,666 years after the Creation, according to a religious tradition. The number does appear in other Bolaño books, but the mentions are equally cryptic. In Amulet, a Mexico City road looks “like a cemetery in the year 2666.” The Savage Detectives contains this: “And Cesárea said something about days to come… and the teacher, to change the subject, asked her what times she meant and when they would be. And Cesárea named a date sometime around the year 2600. Two thousand six hundred and something.”

2666 is a fascinating but depressing read. The failings of human societies and individuals constantly throb through the pages; the horrors of the 20th century, both banal and vicious, underpin everything in mock-documentary style. Readers of The Savage Detectives will immediately find themselves in familiar territory as various characters set off on a pointless quest to physically locate some elusive literary genius. In 2666 four literary academics from France, Germany, England and Italy, are united in their obsession with a cult German novelist, a potential Nobel laureate, Benno von Archimboldi. The four have written endless papers and attended numerous academic conferences on Archimboldi’s novels but are irritated that they know nothing about the man. He is very tall, very old, and vanished as a young man. That’s it — but he has continued to publish novels ever since.

At yet another tedious conference in Toulouse, they find a clue suggesting that Archimboldi recently travelled to a northern Mexican border town called Santa Teresa. The four go there to try tracking him down. Santa Teresa stands in for the actual and notorious border city of Ciudad Juárez, and the horror story of the place pulses throughout the novel like a vibration of evil. It is the still-with-us evil of Nazis, of Holocaust, of Cambodian killing fields, of slaughtered women — of “civilised” societies. Between 1993 and the mid-2000s, Ciudad Juárez gained international notoriety as the femicide capital of the world, with around 370 girls and women murdered, and at least 400 women reported missing. The failure to apprehend those responsible and the general indifference of the local police, authorities and media shocked the world until the shamed central government started taking firm action to halt the crime wave from 2008.

The novel unfolds in the late 1990s, and the fictional literary critics were on their frivolous quest in Santa Teresa at the height of the murder wave. They wander like tourists in a Santa Teresa flea market seeking a bargain in cheap rugs while just beyond their horizon lies a dark vortex of blood and terror and unspeakable acts of violence. Part IV of the novel ends with laughter ringing through the blighted city. This section is about the murdered women, and there’s nothing funny about it, and yet:

“Even on the poorest streets could be heard laughing. Some of these streets are completely dark, like black holes, and the laughter that came from who knows where was the only sign, the only beacon that kept residents and strangers from getting lost.”

Yes, women “getting lost,” never to be seen alive again. Bolaño once told an interviewer he would have preferred to be a homicide detective rather than a writer. “I would have been the sort of person who comes back alone to the scene of a crime by night, unafraid of ghosts.” He never tried to become a detective, but he found plenty of adventure. He was born the son of a truck driver and a teacher, and his parents moved the family to Mexico when he was fifteen. In 1973, Bolaño returned to Chile, where he was arrested as a “foreign terrorist” after military dictator Augusto Pinochet grabbed power in a coup. After a few days, he was released from prison — a guard who had been a former schoolmate intervened. Back in Mexico in 1974, Bolaño co-founded the literary group called the infrarealistas. The movement aimed to challenge the Latin American literary establishment, and they disrupted readings by writers they disapproved of. A Mexican writer, Carmen Boullosa, called the group “the terror of the literary world” and said she dreaded taking a podium to lecture in case lurking infrarealistas lay in wait, ready to pounce.

2666 has plenty of detectives. Part I has the academic investigators doggedly tracking the mysterious Archimboldi. In Parts III and IV, real but corrupt detectives investigate the murders of the women of Santa Teresa. The murders are the evil core of the novel, of the fictional Santa Teresa, of the real Ciudad Juárez, of Mexico, and the whole 20th-century world. They share vast economic inequalities, American-owned factories luring cheap labour to feed the capitalist money machines, violence and corruption, and nearby, a silent, menacing desert. Amid apocalyptic violence, madness and greed, Bolaño scatters his only hope of redemption — the truth of art and the integrity of his bedraggled, impoverished or misunderstood artists. His poets, painters and novelists relentlessly create in the maw of the horror that surrounds them. God is long dead, religion is ridiculous, and only the arts hang on by the skin of their transcendent teeth. One of the critics in Part I, Liz Norton, first discovers Archimboldi as a student when a German friend sends her a copy of one of his novels. Her reaction could describe a reader first looking into Bolaño’s 2666:

“Reading the novel really did make her go running out. It was raining in the quadrangle, and the quadrangular sky looked like the grimace of a robot or a god made in our own likeness. The oblique drops of rain slid down the blades of grass in the park, but it would have made no difference if they had slid up. Then the oblique (drops) turned round (drops), swallowed up by the earth underpinning the grass, and the grass and the earth seemed to talk, no, not talk, argue, their incomprehensible words like crystallised spiderwebs or the briefest crystallised vomitings, a barely audible rustling, as if instead of drinking tea that afternoon, Norton had drunk a steaming cup of peyote. But the truth is that she had only had tea to drink, and she felt overwhelmed … and the rain wetted her grey skirt and bony knees and pretty ankles and little else because before Liz Norton went running through the park, she hadn’t forgotten to pick up her umbrella.”

Many critics have seen in 2666 Bolaño’s debt to Jorge Luis Borges, whom the author admitted admiring greatly. Both writers warned against using literature as a path to respectability, recognition, personal achievement or social status. The authors regarded literature with the eyes of a desert ascetic, as a pilgrimage or even martyrdom. Bolaño once commented that literature is too important to waste time on writing it well.

“But every single damn thing matters! Only we don’t realise. We just tell ourselves that art runs on one track and life, our lives, on another, and we don’t realise that’s a lie.”