by Chris Horner

No man is a hypocrite in his pleasures —Dr Johnson

Without music life would be a mistake —Nietzsche

Music started for me with whatever was blaring out of the radio, and later those 45 rpm ‘single’ records that were the main vehicles of listening pleasure for teenagers in the late twentieth century. I heard a lot of that rather than listened to it. Listening really started with the ‘long player’ or album: 40 minutes or so over two sides of a black disc with a cover that, if you were lucky, didn’t look too bad when you gazed at it.

The first album I owned was a birthday present: Abbey Road, the final Beatles recording. Having nothing else to play, this got a lot of spins, first through the big speakers of my parents ‘Rigonda Stereo Radiogram’, then with the earphones plugged into the back with the lights off. In a private darkness the music and the lyrics were undisturbed by the banality of our front room, and the thing became something I knew by heart, images and melodies imprinted like a recurring, waking dream. Only the pleasure principle mattered: I has no idea whether I was supposed to like this stuff, I just did. Read more »

In the 1990’s Andrei Shleifer was only one among many in the proselytizing army of reformers who went out to the transition economies, mainly in Central and Eastern Europe but also in developing countries, to make them ready for capitalism. They were in a hurry to implement reforms of liberalization and privatization according to some general, often one-size-fits-all, formula. The purse strings of emergency financial help by international organizations like the IMF and the World Bank and US agencies like USAID were also controlled by stern macro-economic ideologues of ‘structural adjustment’. The reformers were in possession of the canonical gospels which it was their sacred duty to spread among the heathens as quickly as possible, given the golden opportunity after the fall of the godless communists and socialists.

In the 1990’s Andrei Shleifer was only one among many in the proselytizing army of reformers who went out to the transition economies, mainly in Central and Eastern Europe but also in developing countries, to make them ready for capitalism. They were in a hurry to implement reforms of liberalization and privatization according to some general, often one-size-fits-all, formula. The purse strings of emergency financial help by international organizations like the IMF and the World Bank and US agencies like USAID were also controlled by stern macro-economic ideologues of ‘structural adjustment’. The reformers were in possession of the canonical gospels which it was their sacred duty to spread among the heathens as quickly as possible, given the golden opportunity after the fall of the godless communists and socialists. “Thus the concept of a cause is nothing other than a synthesis (of that which follows in the temporal series with other appearances)

“Thus the concept of a cause is nothing other than a synthesis (of that which follows in the temporal series with other appearances)

I’m not a schoolteacher so I don’t know the exact routine that teachers have every morning before they leave their house, but I’m certain it shouldn’t involve checking the magazine of a 9mm Glock and perhaps even chambering a round before their commute to school. I have known several teachers and in general, they are idealistic, hard-working, and underpaid. The challenges of teaching 30 hyper 10-year-olds how to write a clear sentence or conquer fractions has to be consuming enough without also having a counter-assault plan in the back of your mind.

I’m not a schoolteacher so I don’t know the exact routine that teachers have every morning before they leave their house, but I’m certain it shouldn’t involve checking the magazine of a 9mm Glock and perhaps even chambering a round before their commute to school. I have known several teachers and in general, they are idealistic, hard-working, and underpaid. The challenges of teaching 30 hyper 10-year-olds how to write a clear sentence or conquer fractions has to be consuming enough without also having a counter-assault plan in the back of your mind.

A UK politician recently suggested that people could combat the cost-of-living crisis by working more hours or getting a better job. This is one more in a long line of instances where societal problems have been framed as being solvable by individual actions. One of the earliest I can remember was when Tory minister Norman Tebbit, following a claim that the riots of 1981 were caused by high unemployment, cited his own father as a salutary example of self-responsibility. ‘I grew up in the 30s with an unemployed father,’ he said. ‘He didn’t riot. He got on his bike and looked for work, and he kept looking till he found it.’ More recently British TV personality Kirsty Alsop recommended that young people start saving earlier and cut out the fancy coffees, gym membership and Netflix subscriptions as a way of combatting unaffordable house prices.

A UK politician recently suggested that people could combat the cost-of-living crisis by working more hours or getting a better job. This is one more in a long line of instances where societal problems have been framed as being solvable by individual actions. One of the earliest I can remember was when Tory minister Norman Tebbit, following a claim that the riots of 1981 were caused by high unemployment, cited his own father as a salutary example of self-responsibility. ‘I grew up in the 30s with an unemployed father,’ he said. ‘He didn’t riot. He got on his bike and looked for work, and he kept looking till he found it.’ More recently British TV personality Kirsty Alsop recommended that young people start saving earlier and cut out the fancy coffees, gym membership and Netflix subscriptions as a way of combatting unaffordable house prices. My mom always told me if I didn’t separate my lights from my darks, I would ding my white laundry. I always thought this was nonsense. And, in fact, in the fancy washing machine in the apartment I shared with my husband, this was nonsense. Oh, I was absolutely reckless! I would toss bright red shirts in with white sheets and black jeans in with cream-colored t’s. And it was always alright in the end. The whites stayed white, and the colors did not fade. I was confident in my millennial assessment that separating the lights from the darks was simply Gen X anxiety, old wisdom, no longer applicable, démodé even.

My mom always told me if I didn’t separate my lights from my darks, I would ding my white laundry. I always thought this was nonsense. And, in fact, in the fancy washing machine in the apartment I shared with my husband, this was nonsense. Oh, I was absolutely reckless! I would toss bright red shirts in with white sheets and black jeans in with cream-colored t’s. And it was always alright in the end. The whites stayed white, and the colors did not fade. I was confident in my millennial assessment that separating the lights from the darks was simply Gen X anxiety, old wisdom, no longer applicable, démodé even.

Fifty years ago this July, newspaper headlines shocked the conscience of the nation with a disturbing story of racial bias and medical mistreatment in one of America’s most honored institutions. The alarming Associated Press story first appeared on July 25, 1972 in the Washington Star. The front page headline, “Syphilis Patients Died Untreated,” caught readers attention. They’d go on to read that the goal of a strange, non-therapeutic experiment conducted by the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) was not to treat the sick or save lives, but “determine from autopsies what the disease does to the human body.”

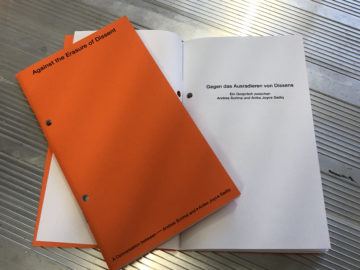

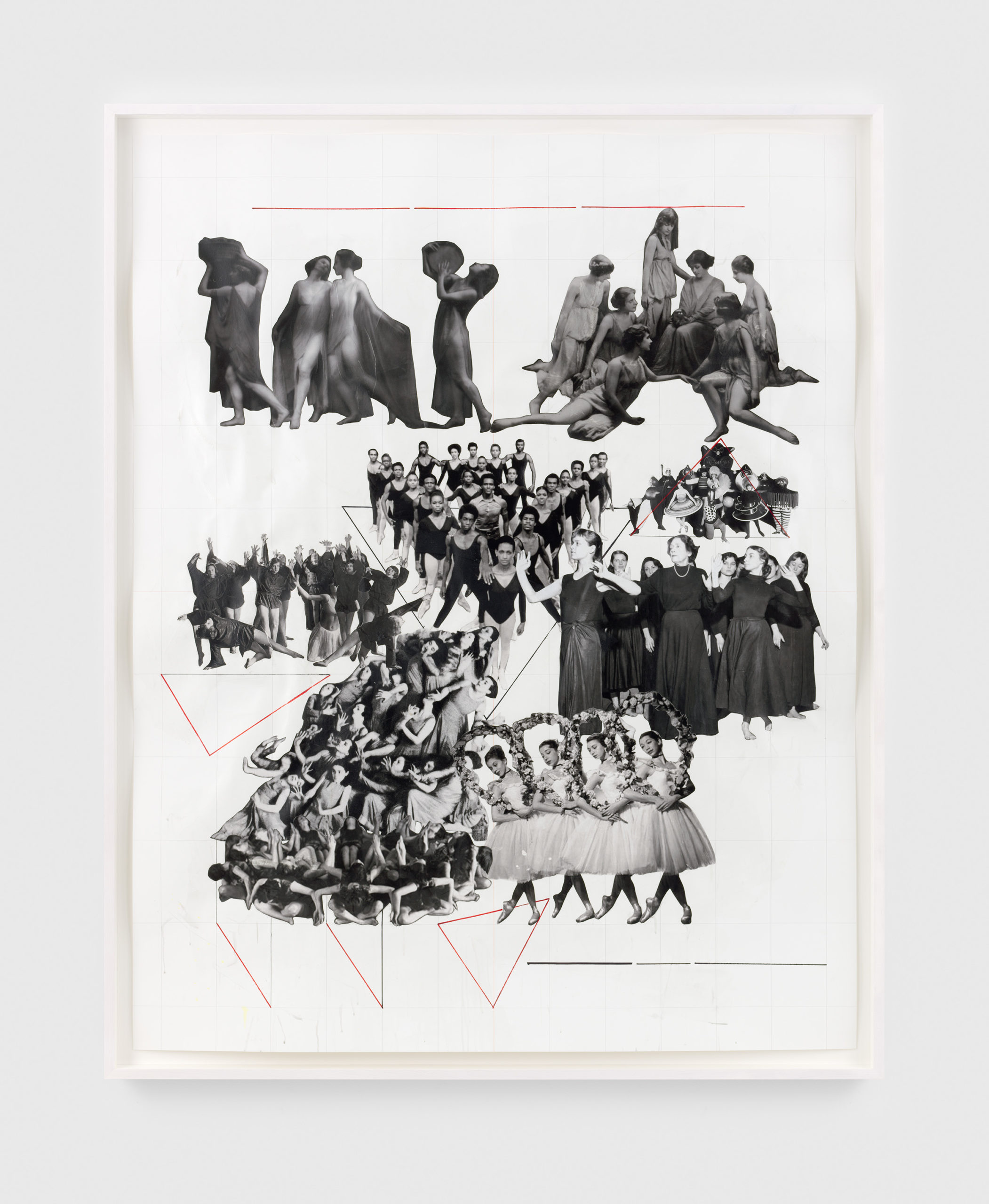

Fifty years ago this July, newspaper headlines shocked the conscience of the nation with a disturbing story of racial bias and medical mistreatment in one of America’s most honored institutions. The alarming Associated Press story first appeared on July 25, 1972 in the Washington Star. The front page headline, “Syphilis Patients Died Untreated,” caught readers attention. They’d go on to read that the goal of a strange, non-therapeutic experiment conducted by the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) was not to treat the sick or save lives, but “determine from autopsies what the disease does to the human body.” Kandis Williams. Triadic Ensemble: stacked erasures, 2021.

Kandis Williams. Triadic Ensemble: stacked erasures, 2021.