by Derek Neal

The character of the American abroad is an archetype in American fiction. By placing the American outside of his native country (usually in Europe), writers such as Henry James and James Baldwin were able to explore what constitutes American identity. More often than not, this identity is revealed in their novels not through what the identity contains, but in what it lacks.

The character of the American abroad is an archetype in American fiction. By placing the American outside of his native country (usually in Europe), writers such as Henry James and James Baldwin were able to explore what constitutes American identity. More often than not, this identity is revealed in their novels not through what the identity contains, but in what it lacks.

Indeed, the American in Europe is an empty vessel. Like the negative of an image, his surroundings are filled in, and the empty space where a person should be appears in outline. Thus, the American has the task of creating his own identity, of forging his own personality without the aid of history or culture but through sheer willpower alone. Whether this is a true representation of what it means to be American is irrelevant; this is the conception that writers have created in literature, giving rise to the myth of the American in Europe. Every time an American character enters Europe, they enter into this legacy, intentionally or not. It is a sort of self-orientalizing, as one can stereotype and mythologize oneself just as one can others.

Henry James and James Baldwin are two progenitors of this genre. For both, the American is a prodigal character and the return to Europe is a return home, to where his real roots lie. The trip to Europe, or the permanent move in some cases, is a search for self-knowledge, and similarly to the biblical Garden of Eden, Europe is often cast as a place of sin and danger, a place one might never escape from if one isn’t careful. Read more »

It is a strange enough thing to collect knives. It is a step stranger still to collect sharpening stones; a further abstraction from reality, an auxiliary activity supporting a hobby which is itself a pantomime of preparedness and practicality. No matter. Once one is lodged firmly enough down a rabbit hole, the only options available are to hope for rescue, or to keep crawling deeper. I have clearly chosen the latter.

It is a strange enough thing to collect knives. It is a step stranger still to collect sharpening stones; a further abstraction from reality, an auxiliary activity supporting a hobby which is itself a pantomime of preparedness and practicality. No matter. Once one is lodged firmly enough down a rabbit hole, the only options available are to hope for rescue, or to keep crawling deeper. I have clearly chosen the latter. I am leaving, and I am taking nothing.

I am leaving, and I am taking nothing.

In Barcelona the daily scramble to deliver children to school results in terrible congestion in the upper part of the city, where the more economically privileged send their children. Watching this phenomenon brings back my own school days, when the most embarrassing thing any of us could imagine was being dropped off by parents. If such a thing were necessary for some unavoidable reason, the kids urged their parents to drop them a short distance away from the school so their peers wouldn’t see them getting out of the car. To be seen being coddled in this way was unimaginably embarrassing, almost as bad as having your mother show up to deliver a forgotten lunch box. Everything about parents tended to be embarrassing and much of the time we pretended not to have any. But there was a single exception to the drop-off rule. If the parents happened to own a 1956 Chevrolet, with its futuristic swept-wing design, then it was obligatory to be dropped off at school on some occasion, even if the ride was for only for a couple of blocks, so the other kids could look with sheer envy on this most prestigious possession.

In Barcelona the daily scramble to deliver children to school results in terrible congestion in the upper part of the city, where the more economically privileged send their children. Watching this phenomenon brings back my own school days, when the most embarrassing thing any of us could imagine was being dropped off by parents. If such a thing were necessary for some unavoidable reason, the kids urged their parents to drop them a short distance away from the school so their peers wouldn’t see them getting out of the car. To be seen being coddled in this way was unimaginably embarrassing, almost as bad as having your mother show up to deliver a forgotten lunch box. Everything about parents tended to be embarrassing and much of the time we pretended not to have any. But there was a single exception to the drop-off rule. If the parents happened to own a 1956 Chevrolet, with its futuristic swept-wing design, then it was obligatory to be dropped off at school on some occasion, even if the ride was for only for a couple of blocks, so the other kids could look with sheer envy on this most prestigious possession.  Since my Chair was in International Trade, most of my teaching in Berkeley was in that field of Economics, both at the graduate and undergraduate levels. The undergraduate classes in Berkeley are large, and mine had sometimes more than 200 students, even though this course was meant mostly for later-year undergraduates. Large classes bring you in close touch (particularly in office hours) with a refreshing diversity of young people. But they also bring other kinds of experience.

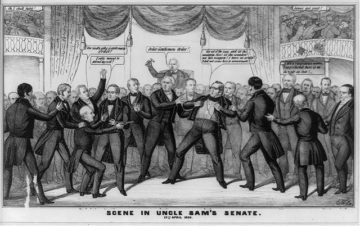

Since my Chair was in International Trade, most of my teaching in Berkeley was in that field of Economics, both at the graduate and undergraduate levels. The undergraduate classes in Berkeley are large, and mine had sometimes more than 200 students, even though this course was meant mostly for later-year undergraduates. Large classes bring you in close touch (particularly in office hours) with a refreshing diversity of young people. But they also bring other kinds of experience. At least Ben was polite about it. The rest of Judge Jackson’s hearing was absolutely awful. If you watched or read or otherwise dared approach the seething caldron of toxicity created by the law firm of Cotton, Cruz, Graham & Hawley (no fee unless a Democrat is smeared) you’ve probably had more than enough, so I’ll try to be brief before getting to more substantive matters.

At least Ben was polite about it. The rest of Judge Jackson’s hearing was absolutely awful. If you watched or read or otherwise dared approach the seething caldron of toxicity created by the law firm of Cotton, Cruz, Graham & Hawley (no fee unless a Democrat is smeared) you’ve probably had more than enough, so I’ll try to be brief before getting to more substantive matters.

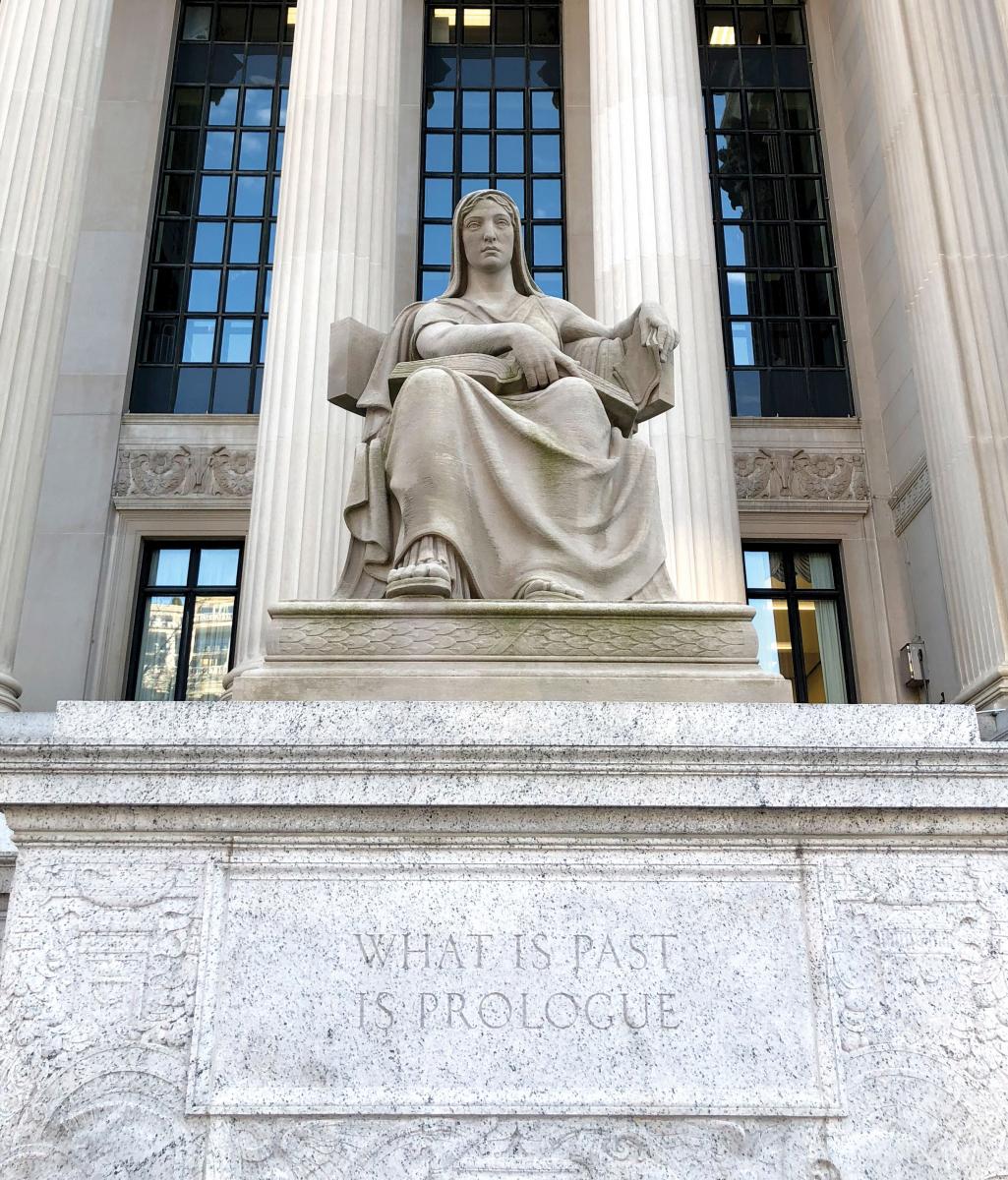

Is the Past Prolog? I’m not convinced. I say this as a professional historian.

Is the Past Prolog? I’m not convinced. I say this as a professional historian. He had a visceral aversion to war, was strongly in favor of social distancing in times of pandemic, and believed it would be a good thing if the Germans turned down their heaters a notch or two.

He had a visceral aversion to war, was strongly in favor of social distancing in times of pandemic, and believed it would be a good thing if the Germans turned down their heaters a notch or two.

Anticipating war in Europe, 2022.

Anticipating war in Europe, 2022. Over the last few weeks, I’ve been spending more time in the office than I have since the start of COVID. I work for a technology start-up, and our New York office used to look and feel just as shows like Silicon Valley portrayed such offices: cool furniture, fancy coffee machines, lots of free snacks, gaming systems and board games piled up in a dedicated room, and lots of young people who gave the office a fun, high energy, even if noisy, vibe. But this visit, while the snacks and coffee machines are still there, the office has a rather ghost town-like feel. There’s been no mandate to return to the office, so for the most part, people haven’t. Every day I saw my colleague Andy who lives in a Manhattan apartment that’s too crowded with family and a dog. He escapes to the office for some peace of quiet. Then there was the receptionist and the facilities manager, who had no choice but to be there. But that was it for regulars. The odd person would float in for a bit, have a meeting, then leave. Is this the future of office life?

Over the last few weeks, I’ve been spending more time in the office than I have since the start of COVID. I work for a technology start-up, and our New York office used to look and feel just as shows like Silicon Valley portrayed such offices: cool furniture, fancy coffee machines, lots of free snacks, gaming systems and board games piled up in a dedicated room, and lots of young people who gave the office a fun, high energy, even if noisy, vibe. But this visit, while the snacks and coffee machines are still there, the office has a rather ghost town-like feel. There’s been no mandate to return to the office, so for the most part, people haven’t. Every day I saw my colleague Andy who lives in a Manhattan apartment that’s too crowded with family and a dog. He escapes to the office for some peace of quiet. Then there was the receptionist and the facilities manager, who had no choice but to be there. But that was it for regulars. The odd person would float in for a bit, have a meeting, then leave. Is this the future of office life?