by Michael Abraham

I have been told it is a bad thing. I have been told this by doctors and friends and my parents and lovers. They worry over me, worry over me the way a Catholic worries over her rosary. They insist on the medication and the therapy and anything but this feeling, anything but this feeling you relish so intensely.

O, but to live without it is a waste, a wasteland, and not in the TS Eliot way: not a wasteland overbrimming with meaning, but a wasteland devoid of even the potential for meaning. Hypomania is summer thunder, is getting crushed by the rain. It is having sex with two men in one night, and learning their names, and learning their deepest fears because one is so open that deep fears tumble out. It is falling into Triangle Park, into the puff-puff warm feeling. It is taking ecstasy on the tongue and dancing all the night long. It is spending all your money and calling it good, for a good night out is only the sign of one who hopes. O, it is sex and drugs and money, but it is more than that, so much more than that. It is a deep thrum like a drum struck at the center of the being, an immaculate sound that emanates through the vibration of the whole body. It is an easy slide into Exactly Who He Wants To Be. The world is an oyster, and hypomania is the pearl: it is gorgeous; it is extravagant; it deserves to be worn at the neck as a sign of glamour and appeal. For one who has experienced it, there is nothing quite as quick as the slice of its blade upon the throat. It bleeds one out. It makes from one who is merely body, merely mind, something spectacular: a fountain of bright red conundrum, a spill of the holy stuff onto the ground. There is no living without it once you’ve had it. It is the best drug on the street. It is top-shelf liquor. It leaves nothing in its wake but wanting for it. Staying up to write all night, sweating profusely as you dance your aches out alone in front of the DJ booth, falling into the arms of any boy, falling into your own embrace, embracing yourself as a broken thing full of yearning: it is a true human condition. It is maybe the human condition laid bare. There is no proper way to say it, but to say that all the stars align for a moment, and in that moment, you are immortal; you are the absolute apotheosis of chance and luck. You take the world in your hands, and then you take the succor of the world in your mouth, and then you fill yourself until your greed for all the world has to offer is finally satiated. O, but it is never satiated!—not until the hypomania passes, and you pass with it, into the doldrums, into the never-ending blue of regret and depressive reconstruction of the self. You lose your ground in the hypomania, and then, in the depression, you get your ground back. And your ground is such a burden. To be free of oneself, to be an onslaught, to be a trick in the back pocket of a satyr prancing wild to a Madonna song: it is so very difficult to leave it. Read more »

The first full moon I saw after the procedure looked as if it might burst, like a balloon with too much helium. It was just above the horizon, fat and dark yellow —moving slowly upward to the firmament where it would later appear smaller and take on a whiter shade of pale. I could distinguish its tranquil seas, the old familiar terrain coinciding with a long abandoned memory.

The first full moon I saw after the procedure looked as if it might burst, like a balloon with too much helium. It was just above the horizon, fat and dark yellow —moving slowly upward to the firmament where it would later appear smaller and take on a whiter shade of pale. I could distinguish its tranquil seas, the old familiar terrain coinciding with a long abandoned memory. Even before the bandage came off, the implant’s ID card seemed to confirm it: I am a camera—with a new Zeiss lens made in Jena. Jena is back in my life.

Even before the bandage came off, the implant’s ID card seemed to confirm it: I am a camera—with a new Zeiss lens made in Jena. Jena is back in my life.

In the middle 1990’s along with journal-editing I did another job in Berkeley which was even more arduous, but also in some ways quite exciting and instructive. I was invited by the campus academic senate to serve for 3 years in a high-powered committee that decided on all appointments, promotions, salaries and merit payment increases for all Berkeley faculty (then roughly about 2,000 in size). This committee is called the Budget Committee in Berkeley; technically it advises the Chancellor, but the latter took our advice in 99% of cases—in the less than 1% cases when the Chancellor did not follow our advice, the rule was that the Chancellor was obliged to meet us in a special session of the committee and explain why he/she would not follow our advice (most often this involved some legal issues) and we had a chance to rebut their arguments.

In the middle 1990’s along with journal-editing I did another job in Berkeley which was even more arduous, but also in some ways quite exciting and instructive. I was invited by the campus academic senate to serve for 3 years in a high-powered committee that decided on all appointments, promotions, salaries and merit payment increases for all Berkeley faculty (then roughly about 2,000 in size). This committee is called the Budget Committee in Berkeley; technically it advises the Chancellor, but the latter took our advice in 99% of cases—in the less than 1% cases when the Chancellor did not follow our advice, the rule was that the Chancellor was obliged to meet us in a special session of the committee and explain why he/she would not follow our advice (most often this involved some legal issues) and we had a chance to rebut their arguments.

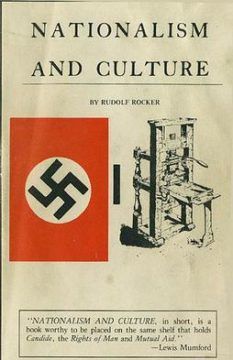

In his book

In his book

Sughra Raza. This Moment … late June 2022.

Sughra Raza. This Moment … late June 2022. I know

I know

Carved in marble above the entrance to the Supreme Court Building is the motto: “Equal Justice Under The Law.”

Carved in marble above the entrance to the Supreme Court Building is the motto: “Equal Justice Under The Law.”