by Derek Neal

As an aspiring writer of fiction, I like to try and understand the mechanics of what I’m reading. I attempt to ascertain how a writer achieves a certain effect through the manipulation of language. What must happen for us to get “wrapped up” in a story, to lose track of time, to close a book and feel that the world has shifted ever so slightly on its axis? The first step, I think, is for writers to persuade readers to believe in the world of the story. In a first-person narrative, this means that the reader must accept the world of the novel as filtered through the subjective viewpoint of the narrator. But it’s not really the outside world that we are asked to accept, it’s the consciousness of the narrator. To create what I’m calling consciousness—basically, a feeling of being in the world—and to allow the reader to experience it is one of the joys of reading. But how does a writer achieve this mysterious feat?

As an aspiring writer of fiction, I like to try and understand the mechanics of what I’m reading. I attempt to ascertain how a writer achieves a certain effect through the manipulation of language. What must happen for us to get “wrapped up” in a story, to lose track of time, to close a book and feel that the world has shifted ever so slightly on its axis? The first step, I think, is for writers to persuade readers to believe in the world of the story. In a first-person narrative, this means that the reader must accept the world of the novel as filtered through the subjective viewpoint of the narrator. But it’s not really the outside world that we are asked to accept, it’s the consciousness of the narrator. To create what I’m calling consciousness—basically, a feeling of being in the world—and to allow the reader to experience it is one of the joys of reading. But how does a writer achieve this mysterious feat?

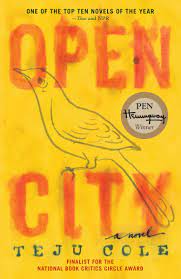

One way may be to have the narrator use language that mirrors and reproduces their inner state. This is often easiest to see in the opening pages of a novel, as this is where a writer will establish a baseline for the story that follows. One such example is Teju Cole’s novel Open City, which begins mid-sentence: “And so when I began to go on evening walks last fall, I found Morningside Heights an easy place from which to set out into the city.” It is a strange sentence with which to begin a story. The “and” implies something prior, but we are oblivious to what this could be. The “so” is a discourse marker, something we would say after a lull in spoken conversation, perhaps to change the subject. But once again, we’re unaware of what the previous subject might be. The effect is that we, as readers, are swept along with the narrator on one of his walks, beginning the novel in step with him, in media res not just in plot but also in terms of grammar.

The walks of the narrator, Julius, are key in understanding him as a character. In the first paragraph of the novel, Julius tells us that “these walks…steadily lengthened, taking me farther and farther afield each time, so that I often found myself at quite a distance from home late at night, and was compelled to return home by subway.” Julius is not the grammatical subject of this sentence but the object instead. He does not walk a great distance; the walks take him, as if he’s got on a means of transport without knowing the destination. He finds himself somewhere unknown, implying that he hasn’t been present during his trip and hasn’t gone there intentionally. Finally, he returns home on the subway not because he chooses to, but because he’s compelled to, forced by some power outside of himself. Similar to a character like Meursault in The Stranger, one wonders if Julius is a sort of Zen sage, perpetually present and so in tune with the world around himself that his own identity disappears—or is it that his lack of assertiveness reveals a fundamental flaw in his character and an unformed sense of self?

As we progress through the story, we learn things about Julius that force us to consider our answer to this question. He seems to have few long-term friends and drifts through New York as a sort of phantom, making acquaintances with people he never sees again. He is estranged from his mother to the point that he doesn’t know where she lives, and he’s recently broken up with his girlfriend. He goes to Belgium apparently in search of his grandmother but makes no real attempt to find her, instead going to dinner with a woman he meets on the plane and chatting with the cashier at a computer café. In a different story, we might demand answers, or at least some sort of explanation on the part of Julius. But none comes, and that’s okay. We implicitly understand Julius because we’ve been primed to accept and understand his way of being via the language he uses to express himself.

Explaining his walks further, Julius says that “not long before this aimless wandering began, I had fallen into the habit of watching bird migrations from my apartment…” Just as he doesn’t decide to walk somewhere, he doesn’t decide to watch birds—he falls into it. While watching birds, Julius says, “I would sometimes listen to the radio…I liked the murmur of the announcers, the sounds of those voices speaking calmly from thousands of miles away…Those disembodied voices remain connected in my mind, even now, with the apparition of migrating geese.” There’s no inherent connection between the sight of birds and radio hosts, but there is for Julius due to his lived experience, and as we read, this connection of sight and sound allows us to step further into his world. This is an experience familiar to all of us, the way seemingly random things become linked in our minds due to an intertwining of the senses: music we listened to at a certain time in our lives comes to signify and represent that period; a taste or smell becomes inextricably linked to a memory of childhood.

This is a sort of meaningful nonsense, vitally important to our understanding of ourselves but unintelligible to others. Here’s one of my examples: eating Werther’s Originals in the back seat of my grandmother’s car. I can’t eat the caramel candy or even see its gold wrapping without being flung back into her 1990’s Buick Skylark, a low-riding boat of a car, more akin to a steamship than an automobile, and complete with carpeted seats that you could draw on with your finger, the tread being dark in one direction and light in the other. I’m sitting behind the driver’s seat, my childhood head straining to see above the window and out into the world beyond.

Proust may be considered the master of this—the famous scene of the madeleine immediately comes to mind—but the very first pages of In Search of Lost Time are equally effective in establishing a sort of dream consciousness of free association, and they bear much in common with the beginning of Open City. Proust’s novel opens with the narrator somewhere between wakefulness and sleep, destabilizing his viewpoint and preparing the reader for the recollections that the madeleine will engender later. The narrator says that “while sleeping, I hadn’t stopped reflecting on what I’d just read, but these reflections had taken a bizarre turn—it seemed that I myself was what the text was talking about: a church, a quartet, the rivalry between Francis I and Charles V. This belief lasted for a few seconds after waking; it didn’t surprise my rational mind but weighed like scales upon my eyes and prevented them from realizing that the candle was no longer lit.” In this state of half-sleep, different times and places meld together, and the barrier between the narrator and the surrounding world collapses.

Echoing Proust’s narrator, Julius talks about reading at night and how “I often fell asleep right there on the sofa, dragging myself to bed only much later, usually at some point in the middle of the night. Then, after what always seemed mere minutes of sleep, I was jarred awake by the beeping of the alarm clock on my cellphone…In these first few moments of consciousness, in the sudden glare of morning light, my mind raced around itself, remembering fragments of dreams or pieces of the book I had been reading before I fell asleep.” Julius refers to these evenings of birds, radio, books, wakefulness, and sleep as a “sonic fugue,” a term that I think captures the state I’m trying to define here.

There are two definitions of “fugue,” a musical one and a psychiatric one, and although they are distinct, they are related in theme. A characteristic of a musical fugue is that it is contrapuntal; it has two or more independent melodies. The first melody, called the subject, is then repeated in the response in other keys or tones, or by another instrument. The subject and response intermingle and play off one another, and more melodies can be added as well. In this way, the subject (the first melody) is modified by being placed within new contexts, and the sum of multiple melodies becomes greater than their individual parts. Julius does something similar as he listens to the radio at night. He reads out loud and says that “I noticed the odd way my voice mingled with the murmur of the French, German, or Dutch radio announcers, or with the thin texture of the violin strings of the orchestras, all intensified by the fact that whatever it was I was reading had likely been translated out of one of the European languages.” Julius is the response to the subject of his book, repeating its text orally after it’s already been repeated in a different tone or key via translation. This then circles back to the original subject via the language of the radio hosts, deepening the sense of fugue and leading Julius to remark that “it wasn’t at all difficult to draw the comparison between myself, in my sparse apartment, and the radio host in his or her booth, during what must have been the middle of the night somewhere in Europe.”

Julius’ comments bring us to the psychiatric definition of fugue, which is defined in the DSM-IV as both “sudden, unexpected travel away from home” and “confusion about personal identity.” From a medical point of view, this is an example of mental illness, but it is also an apt description for what occurs in the stories that we find most meaningful, such as The Odyssey or Don Quixote. Indeed, one could argue that the highest goal of storytelling is to take the reader out of their home, introduce them to new people and places, immerse them in these other worlds and lives, and then return them home, but in a way that who they are and what they believe has changed. In this sense, what Julius describes as a “sonic fugue” is a microcosm of the storytelling process: via literature, music, and sleep, he forgets himself and his apartment to immerse himself in other times, people, and places. As we read his story, we do the same. Whether it’s Julius in Open City, Marcel in In Search of Lost Time, or Meursault in The Stranger, these first person narrators invite us to identify with them and experience what they are experiencing—to enter a fugue state that may linger upon closing the book.