by Mindy Clegg

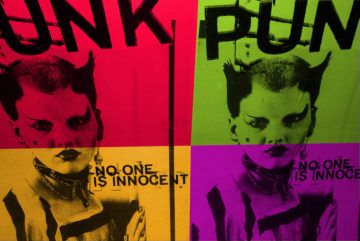

Today punk is a relatively celebrated subculture. Amy Poehler recently directed Moxie, a film about teen girls influenced by the punk riot girl movement of the 1990s, using zines (a self-published magazine popular in punk circles) to combat misogyny at their school. The film includes an appearance from the Linda Lindas, an all-girl punk band from LA covering Bikini Kill’s “Rebel Girl.” Kathleen Hanna of Bikini Kill was recently interviewed with her partner Adam “Adrock” Horowitz of the Beastie Boys by none other than journalist Dan Rather. A recent Guardian article argued that pop punk is the “sound of 2021.” But mainstream culture was not always accepting of punk. During the 1980s, a “punk panic” emerged that positioned punk as a dire threat threat to public order. Punks were cast as nihilistic, destructive, and dangerous villains. Punk panic was found in the west and in the communist East. Two examples are in the US and in East Germany. In both cases, the authorities considered punks to be a danger to the social fabric, showing that during the Cold War, public order was considered critical in both the capitalist west and the communist east.

First wave punk began as an urban subculture in cities like New York, London, and LA. These pioneers were not as alienated from the mainstream culture as later punks were. Some of the most popular New York bands ended up with successful careers in the music industry such as the Ramones, Blondie, and Talking Heads. In London, the first wave bands were relatively successful in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The Sex Pistols had a short career, but had originally signed with EMI, the biggest labels in the UK. Their contemporaries the Clash became genuine rock stars. The LA bands had a harder go of it, as the music industry studious ignored them for years. But even there, the Go-Gos signed to the independent label IRS and had a string of hits on MTV. But in it was in LA and Washington DC where punks began to think more critically about their relationship to the music industry. In 1977 in LA, members of Black Randy & the Metro Squad formed the label Dangerous house to put out local punk bands like X. In DC in 1980 Ian MacKaye and Jeff Nelson formed Dischord Records to put out an EP of their band Teen Idles. Punks turned to independent production out of necessity, but it became a means of maintaining their autonomy. But as punk music got faster and harder, the scenes grew even as they went underground. By the early 1980s, there was a transnational punk underground that had a shared set of cultural practices and democratic counter-institutions.

In the US, during the 1980s some kids in the suburbs discovered punk. Their parents began to worry that their children were disturbed. Mass media depictions of punks had made them seem like members of a dangerous cult or gang. In LA, child psychologist Serena Dank formed an organization called Parents of Punkers and went on the talk show circuit. Talk shows like Donahue introduced punk to their viewers as a serious social problem. Hardcore punk began to appear on TV dramas, such as an episode of of the medical crime drama Quincy ME “Next Stop, Nowhere.” Punks were also targeted by the police. LA was one of the epicenters of hardcore. The LAPD zeroed in on punks as a problem especially prior to the 1984 Olympics. Police brutality was so bad that Black Flag wrote a song about it called Police Story”.

This media engagement made punks seem to be destructive nihilists that posed a danger to families and communities. But in most cases, that was pretty far from the truth. Rather than mindlessly destructive, many of these punks were busy building alternative structures to the mainstream music industry and to other commercial entertainment. By the late 1980s, there were labels, zines, and punk clubs in many American cities that were plugged into a global punk underground. Many punks were becoming more politically aware, too. In the city of Portland, Oregon punks were part of the anti-racist movement there that pushed out white supremacists in the city. As the podcast “It did Happen Here” showed, punks contributed to the building of the anti-fascist movement in the Pacific Northwest that exists today.

In East Germany, the communist government also focused in on punks as an existential threat. In his book Burning Down the Haus Tim Mohr argued that punks contributed to the fall of the Berlin Wall. After discovering punk via illegal British Radio broadcasts, young people started a punk scene that soon came on the government’s radar. Mohr described how punks persevered despite being violently targeted by the Stasi, the East German state security service. These punks rebelled against how much control the state had over their lives in what they called “too much future.” They were also forced to be far more creative, as they had to make everything they had. In the west, most churches would never have embraced punk, but in East Berlin Protestant churches hosted punks and shielded them from the state. Punk became part of the larger set of protest movements against the regime that eventually led to some liberalization prior to the fall of the wall. After reunification, many punks continued their tradition of institution building. In his book, Mohr described how these punks created a strong squatters community that despite pressure from the united German government persisted well into the 1990s.1

Both sides in the Cold War saw punk as a threat. In the US, punks were imagined to be a social threat that needed to be dealt by their families or the local police. The mass media contributed to this general fear of punks. In East Germany, their refusal to conform brought down the power of the Stasi on the scene. Although these realities caused real difficulties for the people involved in the subculture, it also meant that punks in the 1980s were able to build up a robust set of counter-institutions that continue to exist today. They created counter-publics and a strong sense of community that crossed national boundaries. Rather than a social threat, punk proved to be a robust subculture that was and is democratic and constructive. Even as punk is part of the mainstream culture now, these underground scenes continue to provide these spaces for alienated young people.

Footnotes

1 Tim Mohr, Burning Down the Haus: Punk Rock, Revolution, and the Fall of the Berlin Wall, (Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 2018), 350-51.