by Mark Harvey

About five years I bought a quarter horse at an auction in Billings, Montana. The horse was a tall gray four-year-old and showed tremendous speed in the roping events prior to the auction. Kind of a hyped-up, ears-back creature but obviously athletic. Horse auctions are exciting because there’s a lot of money on the line, high stakes, and all kinds of ways things can go wrong. The very term “horse trader” implies clever rogues who have a million ways to disguise old injuries and have no qualms about fobbing off real outlaws as loyal steeds who will always meet you at the gate and never buck.

The horse I bought that day went for a good price and was a registered quarter horse. The name on his papers was JP Perry Bueno, which in the traditional style was a combination from the names of the horse’s sires and dams. His sire was Top Perry and his grandsire was Mr. Jess Perry (hence the JP). I assume the Bueno part was a play on the grandsire of his dam, which was Chicks Beduino. I decided to call him Tatonka for no good reason other than I liked the sound of it. I had looked at his lineage briefly and was familiar with some of his dams and sires but not all.

When I brought the horse back to Colorado he was wired. New locales and new herds stress horses of any age. I was nervous riding him the first few times and, sure enough, he was high-strung and ready to rip at the lightest touch of the legs. But he was fun and could really run. He didn’t look like much of a quarter horse with his long legs and slim build. Read more »

Allison Elizabeth Taylor. Only Castles Burning, 2017.

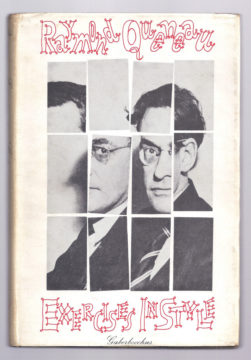

Allison Elizabeth Taylor. Only Castles Burning, 2017. Raymond Queneau was a French novelist, poet, mathematician, and co-founder of the Oulipo group about

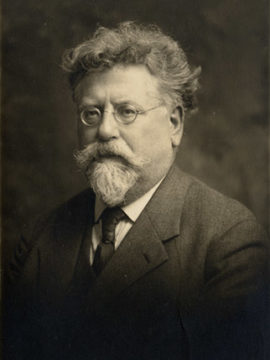

Raymond Queneau was a French novelist, poet, mathematician, and co-founder of the Oulipo group about

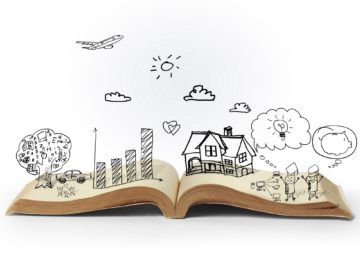

Human minds run on stories, in which things happen at a human level scale and for human meaningful reasons. But the actual world runs on causal processes, largely indifferent to humans’ feelings about them. The great breakthrough in human enlightenment was to develop techniques – empirical science – to allow us to grasp the real complexity of the world and to understand it in terms of

Human minds run on stories, in which things happen at a human level scale and for human meaningful reasons. But the actual world runs on causal processes, largely indifferent to humans’ feelings about them. The great breakthrough in human enlightenment was to develop techniques – empirical science – to allow us to grasp the real complexity of the world and to understand it in terms of

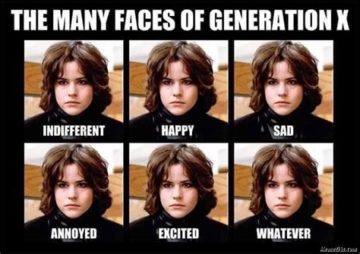

One of the amusing things about academic conferences – for a European – is to meet with American scholars. Five minutes into an amicable conversation with an American scholar and they will inevitably confide in a European one of two complaints: either how all their fellow American colleagues are ‘philistines’ (a favourite term) or (but sometimes and) how taxing it is to be always called out as an ‘erudite’ by said fellow countrymen. As Arthur Schnitzler demonstrated in his 1897 play Reigen (better known through Max Ophühls film version La Ronde from 1950), social circles are quickly closed in a confined space; and so, soon enough, by the end of day two of the conference, by pure mathematical calculation, as Justin Timberlake sings, ‘what goes around, comes around’, all the Americans in the room turn out to be both philistines and erudite.

One of the amusing things about academic conferences – for a European – is to meet with American scholars. Five minutes into an amicable conversation with an American scholar and they will inevitably confide in a European one of two complaints: either how all their fellow American colleagues are ‘philistines’ (a favourite term) or (but sometimes and) how taxing it is to be always called out as an ‘erudite’ by said fellow countrymen. As Arthur Schnitzler demonstrated in his 1897 play Reigen (better known through Max Ophühls film version La Ronde from 1950), social circles are quickly closed in a confined space; and so, soon enough, by the end of day two of the conference, by pure mathematical calculation, as Justin Timberlake sings, ‘what goes around, comes around’, all the Americans in the room turn out to be both philistines and erudite. Sa’dia Rehman. Allegiance To The Flag on Picture Day, 2018.

Sa’dia Rehman. Allegiance To The Flag on Picture Day, 2018.