by Usha Alexander

[This is the fifteenth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

I began writing this series eighteen months ago to explore the human experience and human potential in the face of climate change, through the stories we tell. It’s been a remarkable journey for me as I followed trails of questions through new fields of ideas along entirely unexpected paths of enquiry. New vistas revealed themselves, sometimes perilous, always compelling. And so I went. The more I’ve learned, the more I’ve come to realize that our present environmental predicament is actually far worse off—that is to say, more threatening to near-term human wellbeing and civilizational integrity—than most of us recognize. This journey is changing me. So when I now look at contemporary works of fiction about climate change—so-called cli-fi, which I’d hoped might provide fresh insights—so much of it strikes me as somewhat underwhelming before the task: narrow, shallow, tepid, unimaginative, or even dishonest.

I began writing this series eighteen months ago to explore the human experience and human potential in the face of climate change, through the stories we tell. It’s been a remarkable journey for me as I followed trails of questions through new fields of ideas along entirely unexpected paths of enquiry. New vistas revealed themselves, sometimes perilous, always compelling. And so I went. The more I’ve learned, the more I’ve come to realize that our present environmental predicament is actually far worse off—that is to say, more threatening to near-term human wellbeing and civilizational integrity—than most of us recognize. This journey is changing me. So when I now look at contemporary works of fiction about climate change—so-called cli-fi, which I’d hoped might provide fresh insights—so much of it strikes me as somewhat underwhelming before the task: narrow, shallow, tepid, unimaginative, or even dishonest.

At the same time, a few conclusions have begun to coalesce in my mind. Some of these may seem controversial, largely because they run contrary to the common narratives that anchor our dominant understanding of how the world works—our stories of human exceptionalism, technological magic, and the tenets of capitalist faith. Indeed, many of my own assumptions and worldviews have been challenged, altered, or broken. In their stead, new ways of thinking have taken root, as I began seeing through at least some of our most cherished cultural fabrications to understand our quandary with a different perspective.

Learning these things has been emotionally taxing, but I don’t believe there’s any way forward without a clear-eyed, big-picture view of our planetary and civilizational plight. And so, for better or worse, I wish to sum up my thoughts here, before ending my explorations through this series, which I next expect to turn toward thoughts on how one might respond to it all: hope, despair, expectation, fear, carrying on, looking ahead, finding new stories. I trust there are others out there, who would also rather reckon with what’s happening than go on pretending we needn’t adjust our expectations for the future… although, I confess, there are certainly days when I envy those who are able to go on pretending. What follows isn’t for the faint of heart:

1.

Our mainstream conversations around climate change are frequently delusional. Even as awareness and discussion about the climate crisis surge to the fore, cultural, institutional, political, emotional, and psychological motives conspire to temper the IPCC reports, which drive much of the mainstream coverage. The reports often err toward understating the threats, while they propagate fantasies about proposed mitigations, such as the possibility of capturing and removing vast quantities of carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere. It’s the same with much of the commentary that appears on television; since the talking-heads are there to say what both advertisers and viewers prefer to hear, they tend to avoid connecting all the dots for us. Although, I do notice that, as climate disasters have mounted, scientists and activists are now less frequently been accused of being “alarmist” when they do venture more dire predictions, compared to a year ago.

Still, if one reads the science from multiple sources, across multiple disciplines, and listens to what the scientists are actually saying to each other, the picture looks rather different than what even many well-meaning commentators represent on TV or in the pages of mainstream rags like Newsweek. If one avoids resorting to comforting illusions and magical thinking—from the complacent lies of “net zero” and carbon sequestration to ignoring the consequential lacunae in predictive climate models, including a weak representation of climate feedbacks and tipping points, to presuming the past will be a clear guide to the future or ignoring the material and geopolitical changes the end of oil will itself bring upon civilization, alongside other simplifications and layers of denial—it’s clear we’ll need to brace ourselves for more destabilizing consequences than what the most amplified voices are openly conceding. Not just in the weather, but in all human-centric systems. In all the bounty brought by modern civilization and our certainty of its continuity.

2.

Most concerned people presume climate change is our most overwhelming, existential, planetary crisis, but it is not. We focus on climate change, in part, because its consequences are the first to be experienced with threatening regularity, even by those of us who live sequestered from the life of the land, as it directly assaults our civilizational infrastructure—roads, electricity, food production, shipping ports, etc. But we focus on it also because our understanding of it lets us frame it as a technical problem, so we’re able to take comfort in feeling that it’s solvable within the terms of our present paradigms: we can tell ourselves we simply need to apply more or better technology and market incentives, that we can “fix” it, without fundamentally changing the way we live. But this is a fallacy in our way of thinking. As in that old parable about looking for one’s lost keys under the lamp, because that’s where the light is, being able to frame this problem as tractable within our techno-optimist field of vision helps us avoid looking beyond it.

3.

Climate change is merely a symptom of a far more essential pathology within our global civilization. The larger problem is ecological overshoot: human beings are using resources and creating pollution at a much faster rate than the planet can renew itself, exceeding (and degrading) the sustainable carrying capacity of the land. We’ve all heard that if everyone on the planet tried to live like an average American, we’d need four or five Earth-like planets to support all of us today. Obviously, no such thing is possible. Yet most of our discussion around addressing climate change—all our fond words about Green Growth and renewable energy—is built around the fantasy that something resembling the American way of life can (and must!) be continued, even without the use of fossil fuels. However, as Nate Hagens of the Post Carbon Institute reminds us, even renewable energy is harvested and delivered only through rebuildable technologies, which are themselves non-renewable in their resource requirements; neither are energy sources perfectly interchangeable. We choose not to address the reality that shifting our overexploitation from a dependency upon fossil fuels to a dependency upon sand, copper, niobium, and other minerals required for “clean” technology—all the while, carrying on with all the rest of the ecocidal activities that build our way of life—still leads to environmental breakdown and mass extinction, if through a somewhat different pathway than rapid climate change. The present scale of the human enterprise is plainly unsustainable, no matter what we use to power it. We need to vastly reduce our consumption of energy and other resources. We need to slow our rate of pollution in all forms. We need to halt our annihilation of species and ecosystems and allow them to regenerate on their own terms.

4.

The Holocene climate is behind us. No IPCC plan even claims it can be restored and stabilized within human timeframes, even if we could manage to pull off the best-case scenario of climate-change mitigation and atmospheric carbon capture. In any case, we won’t (or can’t) do this, primarily because doing so would completely upend current geopolitics and every presently entrenched power structure on the globe—not to mention that few of us are ready to give up our accustomed privileges of energy gluttony or that some aspects of the plans, like carbon capture at scale, are in any case beyond feasibility. Following the IPCC recommendations will, at best, slow the warming this century to somewhere around 2ºC above the pre-Industrial baseline (what happens after that remains largely unaddressed).

But even +2ºC of warming will prove ethnocidal for the peoples of small islands, due to sea level rise, and to the peoples of some tropical and subtropical regions, due to lethally rising levels of heat and humidity. It will be disastrous for eight (or nine or ten) billion people tightly dependent upon intensive agriculture and marine harvesting, as once-predictable weather patterns like the monsoons grow more erratic and as ocean life collapses. It will be globally calamitous as scarcity and hunger knock on the doors of even relatively wealthy nations, their borders beset by desperate refugees, convulsing national and global politics. Dealing with any one of these challenges would be tough enough for any nation, but when many countries are dealing with multiple such issues, it will shake up the world. Meanwhile, climate change mitigation requires unprecedented international cooperation to slow planetary warming. And this is not happening.

5.

Global civilization, as presently constituted, isn’t resilient to withstand the environmental onslaughts of the coming decades, not even if we could keep burning fossil fuels, which, obviously, we cannot do, if we hope to arrest future warming. (In any case, the rate of new oil discoveries has consistently fallen behind the global rate of oil consumption for the past thirty years, meaning the end of our present, fossil-fueled civilization is unavoidably nigh, no matter what.) As our planet’s average surface temperature climbs, the human impacts we’re experiencing around the globe, from floods to famines to freezes, will intensify non-linearly, with each additional bit of warming proving worse than the last. Given the vulnerabilities we’re now regularly seeing in our built infrastructures and economic dependencies, including crop production, across the globe at +1.1ºC of warming (as per the IPCC AR6), we can hardly expect our human-built world will hold up well at +1.5ºC—the most optimistically imagined case of future warming—leave alone at +2ºC.

Global civilization will ultimately be transformed in ways that most adults alive today never seriously imagined might follow predictably from the world we grew up in. Different localities will be affected in different ways at different times, and each will also respond in its own way. So there’s no knowing exactly how the human story will play out into the future. But we can presume that life as we’ve come to expect it will change dramatically. Every one of us will be challenged in new ways to find and keep hold of our best selves, as we navigate the coming decades. We will do well to keep our hearts and minds open, individually and collectively, doing whatever we can to welcome the migrants, reduce our own overconsumption, hold fascism at bay, learn new modes of cooperation and manners of trust.

6.

The loss of wild plant and animal biomass and biodiversity is probably the most pressing existential threat to humankind, for we cannot survive as a species without a largely intact biosphere; if this calamity proceeds too far, rapid human extinction is inescapable. We have no idea how far is too far, however, only that the harm already done is well advanced. (As economic anthropologist Jason Hickel reminds us, biodiversity loss is but a strange euphemism for the “mass destruction of nonhuman beings.”) Mainstream environmental news tends to reduce biodiversity and wild biomass loss to a symptom of climate change, but it is not that. It is a separate problem that exacerbates, and is exacerbated by, climate change. Both of these disasters are direct consequences of human ecological overshoot, through overexploitation and over-pollution.

The collapse of the biosphere that we’re witnessing is a matter so complex and superficially understood that we can hardly begin to guess where the tipping points are. (Though, one proposed concerns marine acidification: since the 1940s, oceanic pH has dropped from 8.2 to 8.04; it’s projected to reach a potentially critical threshold of 7.95 within three decades, if we don’t mitigate carbon emissions, leading to the cascading collapse of over eighty percent of marine life.) Nor can we predict just how the consequences will play out for human life or modern civilization; there’s no “modeling” the mass extinction crisis as we do the climate (though, people are earnestly trying). Living systems are even more difficult to reduce to mathematical equations and predictions than is the weather—as we’re now witnessing in the twists and turns of the unfolding Covid-19 pandemic.

The lack of models and projections helps us avoid discussing this mass extinction crisis in terms of the threat that it actually is, as it evades our mechanistic paradigms and slips through our language of techno-solutionism. Some still do try to pretend it can be answered with technology; they dream of “de-extincting” species, like wooly mammoths or giant sloths, as though creating elephant-mammoth chimeras might re-animate swathes of biodiversity or preserve the climate-stabilizing ice and tundra of the vanishing Holocene. But this is a transparently shallow answer to a crisis beyond our ken. Restoring a handful of extinct species, cut off from their historically functioning ecosystems and habituated climate, will not begin to save the biosphere. Nothing less than a wholesale reconfiguration of civilization and a reduced global human population—alongside fallowing and rewilding of at least thirty to fifty percent of the planetary surface—will restore balance to the biosphere such that human societies may be able to rediscover sustainable cultures.

7.

The anthropogenic environmental trauma of the Holocene might still be healed before we demolish the biosphere beyond its capacity to support human life. The ongoing damage is the result of human ecological overshoot, driven by the entrenchment of stark socioeconomic hierarchies and enabled by the rise of peculiar cognitive biases and cultural narratives that promote the domination and dismemberment of the non-human world. The damage has been spread and accelerated by the engine of capitalism, powered by a fossil-energy bonanza. If we stop this ecocide, the biosphere might still find a functional stability that supports human flourishing, with some semblance of a managed civilizational revision. But even slowing the present acceleration of biodiversity loss will require a wholesale transfiguration and scaling down of the human enterprise to find a sustainable equilibrium with the non-human world. It will require revamping our local and global economies, politics, and cultural values so that we can pursue economic degrowth and material circularity in place of capitalism. It requires fostering environmental justice and greater social and economic equality; enabling local stewardship of local resources; reconceiving food production to promote regenerative practices and dismantle factory farming of animals; rapidly retiring fossil-fuels; halting all commercial activity from vast areas of the seas, forests, and other wilderness zones to leave them fallow. Allowing the human population—un-coerced—to peak and steadily decline. And abolishing patriarchy, worldwide.

Achieving all this depends upon global human cooperation of unprecedented scale. It requires a new civilizational paradigm to take root rapidly and globally. While it’s hard to imagine this transition taking place as a calmly managed retreat of the human enterprise across the planet, it yet remains possible that all of these requisite changes will be realized, before it’s too late for humanity in absolute terms—for it does seem likely that the future will hold an unpredictable mix of both managed strategies and unmanaged calamities, ultimately resulting in a dramatic revision of global civilization driven by the changing conditions of the climate and biosphere, alongside the end of oil-based material infrastructures and geopolitics.

8.

Forces working in favor of a managed transition, commensurate with the actions listed above in item 6, are already getting underway, in small ways and large. They are gaining momentum, piecemeal and patch-worked across the globe. Some promising transitions will surely take hold within some communities over the coming decades. Forces working against the same are also well underway, everywhere, and have the advantage of great wealth, entrenched power, inertial continuity, and physical and organizational infrastructure behind them. We can only hope that emergent public awareness might rapidly build into something larger and stronger, as the human consequences of ecological overshoot continue to mount. Caught up in an ongoing contest between factions and ideologies, human civilization will follow an unpredictable and conflicted path—fraught with promise, reversals, and contradictions, as always—into the future. Anything could happen. That is as much a statement of hope as it is of fear.

9.

The world is changing rapidly and the rate of change will accelerate. But it is vital we remember that whatever is to come will be a continuation of the same human drama that’s been playing out for hundreds of millennia. Significant though our social losses may be, they’ll not likely amount to a Sudden Death of History or some fabled return to a state of lawless depravity, such as we mythologize in tales like Mad Max or the Zombie Apocalypse. Humans did not live thus before our modern, techno-capitalist civilization overtook the planet, and it’s not the primary possibility awaiting us should this civilization fail. In fact, such Western-centric, capitalist-colonialist framings of human potentialities aren’t helpful; they’re merely the flip-side of the same hubris that brought on this calamity to begin with. No, our looming tragedy will likely play out in a fashion similar to those that so many have met before, when their social worlds were ended through war, colonialism, genocide, mass enslavement, epidemic disease, ecological overshoot, climate change, volcanic eruption, or other events that have sometimes overwhelmed societies throughout our long past, resulting in destabilizing cultural transformation, institutional simplification, and depopulation: collapse. I say this not to minimize what others have suffered, but to expand it, to recognize our plight in theirs, who have lost before us. The main difference is that this time it will happen to us. To you and to me. To every one of us across the globe. We would do well to ask ourselves, How will I meet this changing world? Who do I want to be, in facing it?

A Different Vantage

Meanwhile, in my various forays for information, perspectives, thoughts, and stories, I came across a singular, low-budget documentary film about our climate and sustainability crisis. Many aspects of this film, wryly titled What a Way To Go, resonated strongly with me. The film covers themes similar to those I’ve been addressing in my own writing; it too speaks about stories and paradigm shifts, about agriculture and overconsumption and our grave error in imagining we are meant to dominate the rest of the living world. But the film’s creator, Timothy S Bennett, comes to these ideas from a very different background than myself and he draws the focus more toward the American culture of empire, its role in bringing us to this point, its interior pathologies.

Hailing from America’s “heartland,” Bennett blurbs his work as: “middle-class white guy comes to grips with Peak Oil, Climate Change, Mass Extinction, Population Overshoot and the demise of the American Lifestyle.” The full-length film follows his journey from the anxious innocence of his youth, through his several interviews with scientists and thinkers over recent years. He describes the predicament of our modern global civilization, based on its material foundations and consequences, with his eye upon the artifice of its purported success. The voices he features, from himself, as narrator, to his interviewees, are monochromatically representative of his particular social location, but I found the film no less moving for that reason. Repurposed vintage television clips set the tone of mid-century Americana, in occasionally surprising ways that expose and subvert its culture of empire. The original musical score draws us in with invisible strings, in a manner unavailable through the written word, imbuing the words and images with elegiac sorrow, tenderness, and anxiety. I found it on the whole thoughtful, insightful, softened with a melancholic humor, and occasionally leaning toward a Koyaanisqatsi-esque vibe. Bennett advises viewers at the start of the film, “Just let it wash over you. And let yourself feel it.” I leave it here for your perusal.

What a Way To Go: Life at the End of Empire

[Part 16: Stories of Continuity. All essays in this series can be read here.]

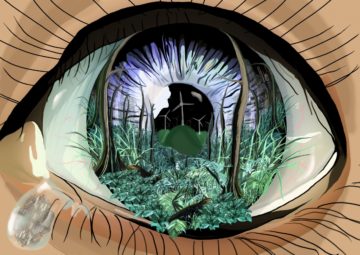

Image

Climate Change: ‘The Eye of the Storm’ by OrganikArts.