by Joseph Shieber

Within the last few weeks, a high ranking official within the municipal government in Philadelphia resigned for making anti-Semitic remarks. Among those remarks, apparently, was the claim that the Holocaust film Schindler’s List was “Jewish propaganda.”

It’s probably a sign that I’ve been thinking about these issues for too long, but my first thought was, Why is it an insult to call something propaganda? What’s wrong with propaganda?

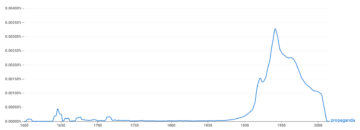

The term “propaganda” itself stems only from the 17th century, when the Catholic Church formed the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide, a committee of cardinals responsible for the Church’s efforts to proselytize non-believers. The use of the term as a denotation for a strategy for influencing public opinion, however, only really exploded at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, as journalism became professionalized. It was then that practitioners, theorists and politicians began to reflect on the ways in which governments and other organizations could use media outlets to shape public opinion.

Here, for example, is the Google Ngram viewer of “propaganda” from 1600 to 2016:

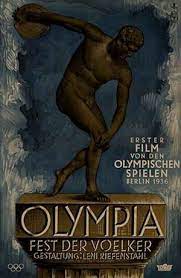

Although the term is less than 400 years old, the phenomenon of propaganda is far older. The pyramids of Egypt, to take one example, are propagandistic, attesting to the power of the Pharaohs who could enslave thousands of people to erect them. (But see this.) So are the coins stamped with the likenesses of the Roman emperors and circulated throughout the Mediterranean.

Given its ubiquity as a phenomenon, it is surprising how meager the theoretical discussion of propaganda actually is. Although there was a surge in works attempting to treat propaganda as a subject of academic inquiry in the first half of the 20th century, since then there have been comparatively few studies of propaganda, apart from largely historical assessments.

Such a lack of sustained investigation would perhaps be more understandable if the glut of early 20th century work had led to widespread agreement about the nature of propaganda. However, scholars were unable to come to agreement – even about the definition of propaganda itself.

On the one hand, many theorists suggested that propaganda is, by its very definition, of negative social value. For example, the eminent psychologist and theorist of propaganda Leonard Doob defined propaganda as “the attempt to affect the personalities and to control the behavior of individuals toward ends considered unscientific or of doubtful value in a society at a given time.” Bertrand Russell suggests that the motive of propaganda “is not the dissemination of knowledge but the generating of some kind of party feeling … in the service of one party to any dispute.” Alex Carey has suggested that propaganda is intended to “close [minds] to the possibility of any conclusion but one.” Edward Bernays suggested that “The only difference between ‘propaganda’ and ‘education,’ really, is the point of view. The advocacy of what we believe in is education. The advocacy of what we do not believe is propaganda.” Finally, the noted propaganda theorist and historian J. Michael Sproule has defined propaganda as representing “the work of large organizations or groups to win over the public for special interests through a massive orchestration of attractive conclusions packaged to conceal both their persuasive purpose and lack of sound supporting reasons.” (The italics in the quotes in this paragraph are all mine.)

In contrast with those more pejorative definitions of propaganda, other theorists have attempted to give a more neutral definition of propaganda. The film theorist (not the philosopher) Richard Taylor, for example, has defined propaganda as “the attempt to influence the public opinions of an audience through the transmission of ideas and values.” Howard Lasswell suggested that “propaganda is concerned with the management of opinions and attitudes by the direct manipulation of social suggestion.” Jacques Ellul — in Randal Marlin’s loose translation — defined propaganda as a “means of gaining power by the psychological manipulation of groups or masses, or of using this power with the support of the masses.”

One way, then, in which propaganda definitions have failed to align concerns the extent to which those definitions are negative – emphasizing misinformation, for example, or deception, as a requirement for propaganda – or neutral. A second way in which definitions have differed is the extent to which they emphasize linguistic communication as an essential medium for propaganda. Those definitions that exclusively focus on language as the medium of propaganda are clearly deficient, since it ought to be obvious – if only from the examples of the pyramids or the Roman imperial coins with which I began this discussion – that propaganda encompasses non-linguistic phenomena. The political scientist and propaganda specialist Bruce L. Smith emphasized this, in noting that propaganda involves “symbols (words, gestures, banners, monuments, music, clothing, insignia, hairstyles, designs on coins and postage stamps, and so forth).”

I’ve just suggested that there are good reasons to prefer definitions of propaganda that do not limit their focus exclusively to linguistic communication. There also seem to me to be good reasons to prefer neutral definitions of propaganda to explicitly negative ones. In particular, it ought to be possible to identify a piece of artwork, a radio broadcast, or a poster, for example, as propagandistic without having first to pass judgment on the rightness of the cause for which that artwork, broadcast, or poster was produced or the truth of its message.

With these considerations in mind, my definition of propaganda is as follows:

Propaganda involves the orchestrated attempt to affect beliefs, attitudes, or actions regarding a matter of public concern using methods that are designed to influence the public in ways that bypass reflective thought.

Not all forms of social influence on matters of public concern that bypass reflective thought are propagandistic. The other important phenomenon to consider is that of ideology. As in the case of propaganda, considering the importance of ideology as a phenomenon, it is surprising how little agreement there is concerning its definition. Indeed, it’s surprising how few theorists have even attempted a definition.

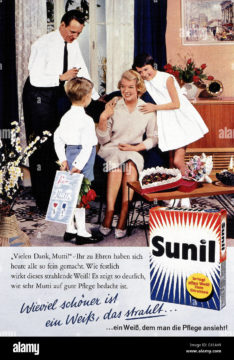

To see the difference between propaganda and ideology, consider this 1950’s German advertisement for laundry detergent:

The goal of the creator of this piece of advertising, of course, is to sell Sunil detergent. The messages that the advertisement conveys, however, go far beyond merely, “Buy Sunil.”

The German text reads, “‘Many thanks, Mom!’ – To honor her today everyone has dressed so finely. This gleaming white looks so festive! It shows so clearly how much Mom cares about good housekeeping.”

The messages conveyed by the idyllic family image, underscored by the text, are unmistakable – that the wife is responsible for the home, that the love of her children and husband are contingent on her being a good caregiver, that the cleanliness of her children’s and her husband’s clothes is a reflection on her worth. In other words, while the advertisement is explicitly selling laundry detergent, it is implicitly selling patriarchy and heteronormativity. Though not a piece of propaganda, it is a vehicle of ideology.

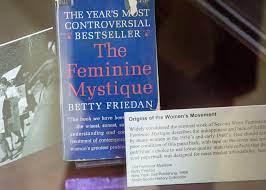

To appreciate this, recall this quote from Betty Friedan’s 1963 work, The Feminine Mystique, about how the interest of the editors of so-called “women’s” magazines is “in selling them the things that interest advertisers— appliances, detergents, lipstick. Today, the deciding voice on most of these magazines is cast by men. Women often carry out the formulas, women edit the housewife ‘service’ departments, but the formulas themselves, which have dictated the new housewife image, are the product of men’s minds.”

As Friedan also notes, the underlying ideological message of these advertisements is not an explicit goal of the marketers. “I am sure the … assorted directors of all the companies that make detergents and electric mixers, and red stoves with rounded corners, and synthetic furs, and waxes, and hair coloring … never sat down around a mahogany conference table in a board room on Madison Avenue or Wall Street and voted on a motion: ‘Gentlemen, I move, in the interests of all, that we begin a concerted fifty-billion-dollar campaign to stop this dangerous movement of American women out of the home. We’ve got to keep them housewives, and let’s not forget it.’”

This suggests a definition of ideology that highlights the ways in which ideology operates without being explicitly intended.

With this in mind, my definition of ideology is as follows:

Ideology involves symbols, concepts or broader social mechanisms or structures that, in ways not explicitly intended by the creators of those symbols, concepts or mechanisms, promote particular political, economic or social interests through effects that typically bypass or go undetected by reflective thought.