by Mindy Clegg

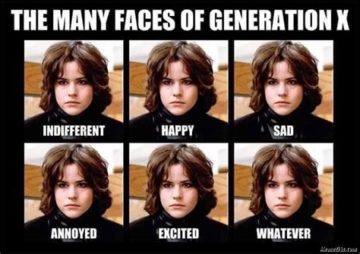

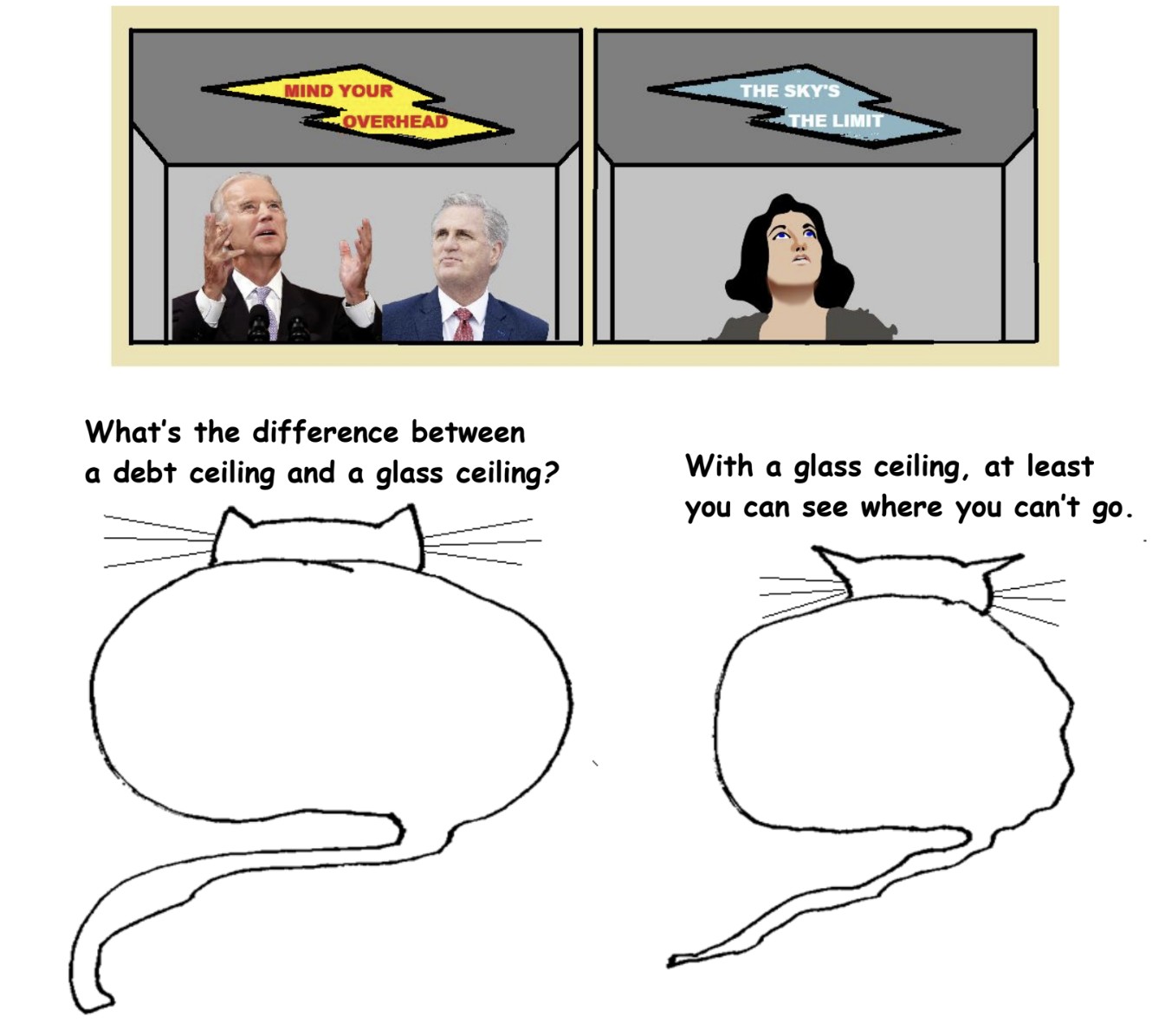

In a thread on a Gen X subreddit, a poster named QueenShewolf wondered about the truth of Gen X cynicism as her own Gen X siblings seemed far less “cynical and disconnected” than herself, a millennial. Some responded that they were certainly cynical, others felt they were merely realistic. Skepticism drove some of this more cynical or realistic worldview, based on their experiences growing up in the 70s and 80s. Many expressed distrust of institutions because of growing up during Watergate and the Reagan administration. Cynicism has its uses, according to the posters in the thread. Being at least a bit cynical about the world around you can help you engage more critically for one. But is too much cynicism dangerous for making positive social change? Has Gen X adoption of cynicism meant that our generation has been less engaged in larger social and political life, leaving it to other generations to shape? While there is some truth in the charges of ironic cynicism, some of that has been imposed on us from without. I argue that Gen X has made some positive contributions to our culture that are often overlooked. Our generation might be more cynical, but we also helped to create durable non and even anti-commercial culture, despite our paucity of numbers.

The term Generation X came to describe to the generation that was born from the mid-60s to early 80s. The term was popularized by Douglas Coupland, a baby boomer. Paula Gottula Miles said that he settled on the “X” to illustrate how this generation had no great existential experiences unifying them “unlike previous generations.” Instead, “they do have as a unifying childhood experience … a phenomenal rise in the divorce rates, and a national debt that went from the millions to the billions.” Such shared experiences (which are apparently less meaningful than wars or political assassinations) meant they shared a common cynicism, as illustrated by his work.1 But I would argue that Coupland ignored major events that had a formative impact, such as the Reagan era weapons build-up, the end of the Cold War itself, and several major conflicts that saw major acts of genocide (Yugoslavia and Rwanda). Read more »

Human minds run on stories, in which things happen at a human level scale and for human meaningful reasons. But the actual world runs on causal processes, largely indifferent to humans’ feelings about them. The great breakthrough in human enlightenment was to develop techniques – empirical science – to allow us to grasp the real complexity of the world and to understand it in terms of

Human minds run on stories, in which things happen at a human level scale and for human meaningful reasons. But the actual world runs on causal processes, largely indifferent to humans’ feelings about them. The great breakthrough in human enlightenment was to develop techniques – empirical science – to allow us to grasp the real complexity of the world and to understand it in terms of

One of the amusing things about academic conferences – for a European – is to meet with American scholars. Five minutes into an amicable conversation with an American scholar and they will inevitably confide in a European one of two complaints: either how all their fellow American colleagues are ‘philistines’ (a favourite term) or (but sometimes and) how taxing it is to be always called out as an ‘erudite’ by said fellow countrymen. As Arthur Schnitzler demonstrated in his 1897 play Reigen (better known through Max Ophühls film version La Ronde from 1950), social circles are quickly closed in a confined space; and so, soon enough, by the end of day two of the conference, by pure mathematical calculation, as Justin Timberlake sings, ‘what goes around, comes around’, all the Americans in the room turn out to be both philistines and erudite.

One of the amusing things about academic conferences – for a European – is to meet with American scholars. Five minutes into an amicable conversation with an American scholar and they will inevitably confide in a European one of two complaints: either how all their fellow American colleagues are ‘philistines’ (a favourite term) or (but sometimes and) how taxing it is to be always called out as an ‘erudite’ by said fellow countrymen. As Arthur Schnitzler demonstrated in his 1897 play Reigen (better known through Max Ophühls film version La Ronde from 1950), social circles are quickly closed in a confined space; and so, soon enough, by the end of day two of the conference, by pure mathematical calculation, as Justin Timberlake sings, ‘what goes around, comes around’, all the Americans in the room turn out to be both philistines and erudite. Sa’dia Rehman. Allegiance To The Flag on Picture Day, 2018.

Sa’dia Rehman. Allegiance To The Flag on Picture Day, 2018.

In the first round of this year’s NBA playoffs, Austin Reaves, an undrafted and little-known guard who plays for the Los Angeles Lakers, held the ball outside the three-point line. With under two minutes remaining, the score stood at 118-112 in the Lakers’ favor against the Memphis Grizzlies. Lebron James waited for the ball to his right. Instead of deferring to the star player, Reaves ignored James, drove into the lane, and hit a floating shot for his fifth field goal of the fourth quarter. He then turned around

In the first round of this year’s NBA playoffs, Austin Reaves, an undrafted and little-known guard who plays for the Los Angeles Lakers, held the ball outside the three-point line. With under two minutes remaining, the score stood at 118-112 in the Lakers’ favor against the Memphis Grizzlies. Lebron James waited for the ball to his right. Instead of deferring to the star player, Reaves ignored James, drove into the lane, and hit a floating shot for his fifth field goal of the fourth quarter. He then turned around