by Raji Jayaraman

Unspeakable horrors transpired during the genocide of 1994. Family members shot family members, neighbours hacked neighbours down with machetes, women were raped, then killed, and their children forced to watch before being slaughtered in turn. An estimated 800,000 people were murdered in a country of (then) eight million. Barely thirty years have passed since the Rwandan genocide. Everywhere, there are monuments to the dead, but as an outsider I see no trace of its shadow among the living.

Unspeakable horrors transpired during the genocide of 1994. Family members shot family members, neighbours hacked neighbours down with machetes, women were raped, then killed, and their children forced to watch before being slaughtered in turn. An estimated 800,000 people were murdered in a country of (then) eight million. Barely thirty years have passed since the Rwandan genocide. Everywhere, there are monuments to the dead, but as an outsider I see no trace of its shadow among the living.

Colleagues chat in the office. Ordinary Rwandans go about their daily business. Walking down the street, eating at restaurants, driving motorcycles, selling wares, chatting, laughing. So much laughter everywhere. How? How is it possible for people to get on with their lives as nothing ever happened, when trauma must be etched in the memory of almost every living adult in the country? How do you casually interact with people who, for all you know, are directly implicated in the murder of those you loved? It is a mystery to me. I am baffled and wonderstruck all at once.

When studying colonial history in school, I remember learning that in Rwanda, the Tutsi minority ruled over the Hutu majority for ages. It made sense to me when the genocide was explained as a contemporary, albeit extreme, manifestation of a centuries-old enmity. The Kigali Genocide Memorial’s audio guide disputes this origin story. It claims that while the Hutu and Tutsi did constitute different groups with important class differences, historically there was a great deal of fluidity between them through both intermarriage and economic mobility.

Visitors to the memorial are informed that it wasn’t until German colonizers arrived in Rwanda during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, that the sharp distinction between Hutu and Tutsi was codified with the help of pseudo-science. We are shown chillingly familiar pictures of Germans using callipers to measure the length of Tutsi and Hutu noses, distances between their eyes, and sizes of their foreheads. Read more »

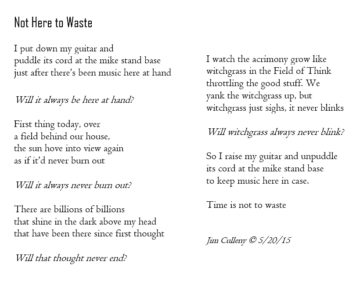

Barbara Chase-Riboud. Untitled (Le Lit), 1966.

Barbara Chase-Riboud. Untitled (Le Lit), 1966.

One of the easy metaphors, easy because it just feels true, is that life is like a river in its flowing from then to whenever. We are both a leaf floating on it, and the river itself. Boat maybe. Raft more likely. But those who know such things say there is a river beneath the river, the hyporheic flow. “This is the water that moves under the stream, in cobble beds and old sandbars. It edges up the toe slope to the forest, a wide unseen river that flows beneath the eddies and the splash. A deep invisible river, known to its roots and rocks, the water and the land intimate beyond our knowing. It is the hyporheic flow I’m listening for.” The person speaking is Robin

One of the easy metaphors, easy because it just feels true, is that life is like a river in its flowing from then to whenever. We are both a leaf floating on it, and the river itself. Boat maybe. Raft more likely. But those who know such things say there is a river beneath the river, the hyporheic flow. “This is the water that moves under the stream, in cobble beds and old sandbars. It edges up the toe slope to the forest, a wide unseen river that flows beneath the eddies and the splash. A deep invisible river, known to its roots and rocks, the water and the land intimate beyond our knowing. It is the hyporheic flow I’m listening for.” The person speaking is Robin There is a scene near the end of First Reformed, the 2017 film directed by Paul Schrader, where the pastor of a successful megachurch says to the pastor of a small, sparsely attended church:

There is a scene near the end of First Reformed, the 2017 film directed by Paul Schrader, where the pastor of a successful megachurch says to the pastor of a small, sparsely attended church:

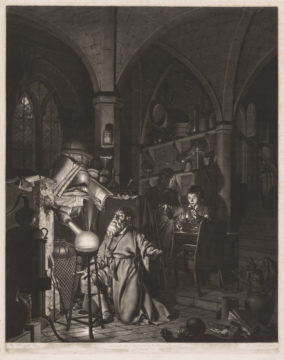

Maria Berrio. From the series “In A Time of Drought”.

Maria Berrio. From the series “In A Time of Drought”. The Lede

The Lede 1.

1.