by Tamuira Reid

Gordon, 74, Crown Heights, Retired Vet and Woodworker

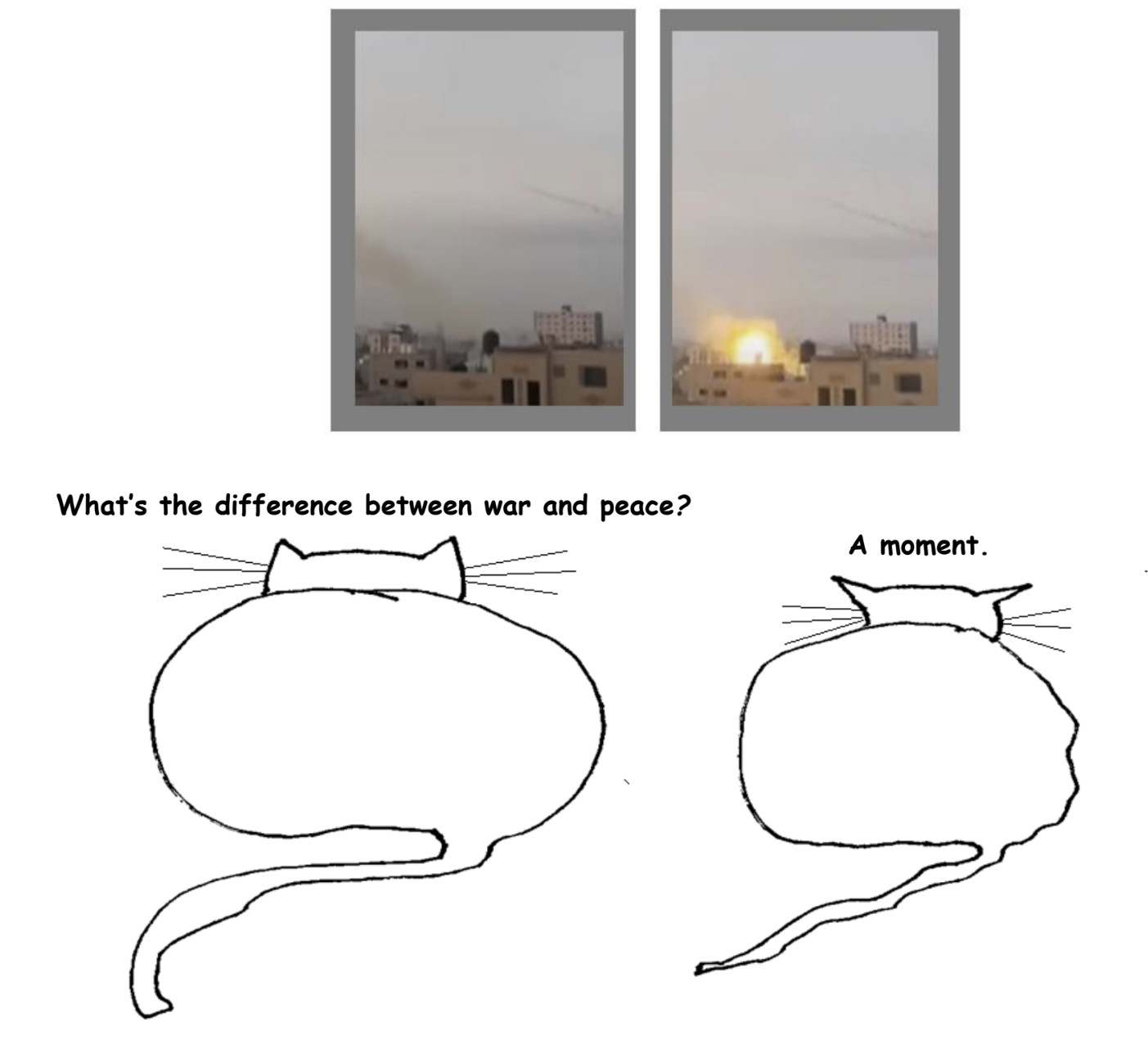

I saw my best friend, my platoon mate in Nam, get his entire head blown off right in front of me. The whole thing. Nothing left from the neck up. A soldier, a kid really, suddenly without a head. It was there and then it was gone. He was there and then he was gone. Like everything else there, up for grabs. Nothing lasts forever was more like nothing lasts for a minute. No one lasted even if they made it out of there alive. But I don’t wanna get into that. Anyway, so me and him we’d been playing cards the night before and were talking shit like normal, probably about our women back home. He had a few but he was a good guy. Loved his country. Proud. Never questioned our government like some of the other guys did. Pure patriot. So he gets his head blown off and I’m telling you, that was the day I said to hell with all of this. We’re all gonna die out here and for what? Some problems you just can’t fix, no matter how many grenades you got. So I look at Israel and Palestine and that beef goes back longer than anyone here understands. You can’t just say “we own you” and then not think that maybe, maybe one day there will be a price on your head for that. Sleeping giants is what happened. Israel got too comfy thinking Palestine was accepting being owned. Never. Those motherfuckers will never accept that. They out for blood. Can’t say I blame them. The most dangerous people in the world are the ones who have nothing to lose because it’s all been taken from them. And the worst thing outside of death you can take from any man is his freedom. I’m an old Black man living in America. I’ve seen some shit. This country always likes a good villain. They need one. If it isn’t me, then it’s the Arab down the block, you know what I mean? But the US needs to stay out of this. Giving all this money to Israel to blow away anything that moves in Gaza sure looks a hell of a lot like 9/11. And how did that go for us? For the world? I served my country but I would not do it again blindly. My faith has limits. Vietnam destroyed my faith in a lot ways. I have faith in God but I would never put a uniform on again. I’m too damn old anyway. Read more »

In 1970, Pier Paolo Passolini directed a film titled Notes Towards an African Orestes, which presents footage about his attempt to make a movie based on the Oresteia set in Africa. The movie was never made. In the same way, this article will be about a series of essays, or perhaps a book, that may never be written.

In 1970, Pier Paolo Passolini directed a film titled Notes Towards an African Orestes, which presents footage about his attempt to make a movie based on the Oresteia set in Africa. The movie was never made. In the same way, this article will be about a series of essays, or perhaps a book, that may never be written. Without really looking into them, I have always felt sceptical of Kantian approaches to animal ethics. I never really trust them to play well with creatures who are different from us. Only recently, I cared to pick up a book to see what such an approach would actually look like in practice: Christine Korsgaard’s Fellow creatures (2018). An exciting and challenging reading experience, that not only made a very good case for Kantianism (of course), but also forced me to come to terms with some rather strange implications of my own views.

Without really looking into them, I have always felt sceptical of Kantian approaches to animal ethics. I never really trust them to play well with creatures who are different from us. Only recently, I cared to pick up a book to see what such an approach would actually look like in practice: Christine Korsgaard’s Fellow creatures (2018). An exciting and challenging reading experience, that not only made a very good case for Kantianism (of course), but also forced me to come to terms with some rather strange implications of my own views.

The force of recent attempts to increase minority visibility in the performing arts, principally in the US, by matching the identity of the performer with that of the role—in effect a form of affirmative action—has been diminished by a series of tabloid “scandals”: the casting of Jared Leto as a trans woman in Dallas Buyers Club

The force of recent attempts to increase minority visibility in the performing arts, principally in the US, by matching the identity of the performer with that of the role—in effect a form of affirmative action—has been diminished by a series of tabloid “scandals”: the casting of Jared Leto as a trans woman in Dallas Buyers Club  1.

1. Jeannette Ehlers. Black Bullets, 2012.

Jeannette Ehlers. Black Bullets, 2012. How plastic – really plastic – gelatin presents as a food. Not only in the “easily molded” sense of a pliable art material but also its transparency. Walnuts and celery, the “nuts and bolts” of gelatin desserts, defy gravity, floating amidst the cheerful jewel-like plastic-looking splendor of the 1950’s, when gelatin was the king of desserts. Gelatin’s mid-century elegance belies its orgiastic sweetness, especially the lime flavor, which is downright otherworldly. If you stir it up hot, half diluted, gelatin lives up to its derelict reputation with regard to the sickbed and sugar, being thick and warm, twice as intoxicatingly sweet, and surely terrible for an invalid’s teeth, if not metabolism. In my novel, Dog on Fire, I hypothesize that lime-flavored gelatin is the perfect murder weapon.

How plastic – really plastic – gelatin presents as a food. Not only in the “easily molded” sense of a pliable art material but also its transparency. Walnuts and celery, the “nuts and bolts” of gelatin desserts, defy gravity, floating amidst the cheerful jewel-like plastic-looking splendor of the 1950’s, when gelatin was the king of desserts. Gelatin’s mid-century elegance belies its orgiastic sweetness, especially the lime flavor, which is downright otherworldly. If you stir it up hot, half diluted, gelatin lives up to its derelict reputation with regard to the sickbed and sugar, being thick and warm, twice as intoxicatingly sweet, and surely terrible for an invalid’s teeth, if not metabolism. In my novel, Dog on Fire, I hypothesize that lime-flavored gelatin is the perfect murder weapon.

Barring that reality, and knowing this would be an ongoing, lifelong issue, I got a tattoo on my Visa-paying forearm to remind myself that my actions affect the entire world. I borrowed Matisse’s

Barring that reality, and knowing this would be an ongoing, lifelong issue, I got a tattoo on my Visa-paying forearm to remind myself that my actions affect the entire world. I borrowed Matisse’s

I am sitting on the couch of our discontent. The Robot Overlords™ are circling. Shall we fight them, as would a sassy little girl and her aging, unshaven action star caretaker in the Hollywood rendition of our feel good dystopian future? Shall we clamp our hands over our ears, shut our eyes, and yell “Nah! Nah! Nah! Nah! Nah!”? Shall we bow down and let the late stage digital revolution wash over us, quietly and obediently resigning ourselves to all that comes next, whether or not includes us?

I am sitting on the couch of our discontent. The Robot Overlords™ are circling. Shall we fight them, as would a sassy little girl and her aging, unshaven action star caretaker in the Hollywood rendition of our feel good dystopian future? Shall we clamp our hands over our ears, shut our eyes, and yell “Nah! Nah! Nah! Nah! Nah!”? Shall we bow down and let the late stage digital revolution wash over us, quietly and obediently resigning ourselves to all that comes next, whether or not includes us? I first became aware of Miriam Lipschutz Yevick through my interest in human perception and thought. I believed that her 1975 paper,

I first became aware of Miriam Lipschutz Yevick through my interest in human perception and thought. I believed that her 1975 paper,

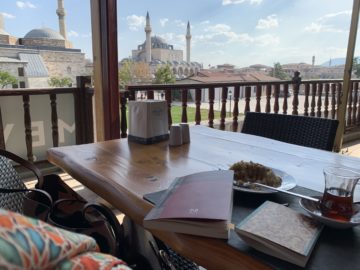

At dusk, the shaft of light striking Rumi’s tomb is emollient as pale jade. It has been a long, hot day in Konya, I’ve been writing in a café-terrace overlooking the famed white and turquoise structure of the tomb-museum complex. I sip my tea slowly, facing the spare, elegant geometry of the building that appears as a simple, intimate inscription on the vast blue. For once I am studying Rumi’s verses in Persian, not repeating English translations or paraphrasing in Urdu. “Bash cho Shatranj rawan, khamush o khud jumla zaban,” “Walk like a chess piece, silently, become eloquence itself!” I’m reciting to myself in the din, in awe of the kind of magnetism that would pull one as a chess piece. Only the heart understands this logic, not any heart, but the one that has been broken open, the one that is led to the mystery in cogent silence.

At dusk, the shaft of light striking Rumi’s tomb is emollient as pale jade. It has been a long, hot day in Konya, I’ve been writing in a café-terrace overlooking the famed white and turquoise structure of the tomb-museum complex. I sip my tea slowly, facing the spare, elegant geometry of the building that appears as a simple, intimate inscription on the vast blue. For once I am studying Rumi’s verses in Persian, not repeating English translations or paraphrasing in Urdu. “Bash cho Shatranj rawan, khamush o khud jumla zaban,” “Walk like a chess piece, silently, become eloquence itself!” I’m reciting to myself in the din, in awe of the kind of magnetism that would pull one as a chess piece. Only the heart understands this logic, not any heart, but the one that has been broken open, the one that is led to the mystery in cogent silence.