by Michael Liss

There was a sense everywhere, in 1968, that things were giving. That man had not merely lost control of his history, but might never regain it. —Garry Wills, Nixon Agonistes: The Crisis of the Self-Made Man

Last month, I wrote about Eugene McCarthy’s Vietnam-based primary challenge to Lyndon Baines Johnson’s reelection campaign, the angst-ridden mid-March entry into the race by Robert F. Kennedy, and LBJ’s stunning withdrawal on March 31, 1968. I ended with April 4, when the “Dreamer,” Martin Luther King, was assassinated.

Some of the chaos that ensued is the subject of this piece. “Things were giving,” seemingly everywhere, and all at the same time. America’s ability to deflect the course of history as it accelerated toward the unknown was disappearing. The months that followed the King assassination were punctuated by more violence, more uncertainty, and the continued deterioration of social discourse.

None of this appeared out of thin air. Grassroots efforts on Vietnam and on civil rights had been intensifying for years, as had been the backlash to those movements. FDR’s New Deal coalition was fraying, most notably in the South, but also in the industrial Midwest. 1968 was also to be the last stand of the “Liberal” Republicans, people like Nelson Rockefeller, Charles Percy, and John Lindsay. We think about them and their ambitions with an amused raised eyebrow, but, at the time, they were men of reputation and influence.

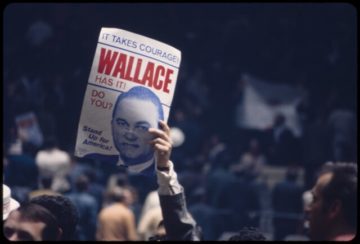

There were so many crosscurrents, so many strange alliances, that it’s difficult to trace each causation, but if you want to pick up on an organizing thread other than Vietnam, look to George Wallace. History frames Wallace largely as the segregationist that he was (after losing his first run for office for being more moderate than his opponent, he vowed “never to be out-n…ed again”). It sometimes skips over how Wallace had a broader message, anchored by the emotional appeal of his racism, but also including perennial themes of law and order and economic and social grievances that resonated in people’s lives.

Wallace announced his candidacy in March 1968 under the new American Independent Party banner. Conventional wisdom was that its goal was similar to that of Strom Thurmond’s Dixiecrat effort in 1948—to win enough Southern States to deny either candidate an Electoral College win, throw it into the House, and then bargain with both sides to obtain a segregationist promise/free hand in dealing with racial and “local” issues.

That might have been an impetus for Wallace’s run, and its potential success certainly was a legitimate fear of the Establishment in both parties. Letting a minority dictate terms to the majority is immensely destabilizing to a system such as ours. It’s even more true when that minority intends to exercise that power to legalize oppression and abuse. What some of the professionals weren’t fully attuned to, at least at first, was a truth that Wallace felt instinctively—that he could be a national figure by exploiting a much larger issue than just open, virulent racism. There was also a market in fear, in economic dislocation, and in cultural resentment, and that extended well beyond the Mason-Dixon Line.

Just about every poll and just about every potential candidate match-up initially had Wallace in the mid-teens, and then, by September, rising to the 20% level. He ultimately fell back on Election Day to 13% (the disastrous selection of General Curtis LeMay as his Veep certainly hurt his numbers), but he still managed at least 10% in these outside-the-South states: Alaska, Delaware, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Nevada, and Ohio.

Many third-party candidacies wither, but stay on to be vanity campaigns—certainly that was true with candidates like John Anderson and Ross Perot. Wallace was different. He certainly had plenty of vanity, but he was also purposeful, and he had a message other than “change.” What Wallace did was articulate some of the resistance that LBJ had been encountering in trying to build on his Great Society initiatives. As farsighted as those programs had been, they nevertheless upset the existing order, in effect redistributing both economic and social capital. At the very same time the failed promise of a more just society had led to impatience in some parts of the Black community with Dr. King’s message of non-violence. Layer into that Wallace’s pungent rejection of the counterculture for its disdain of traditional values and opposition to the Vietnam War, and you had the perfect tuning fork for a certain type of vibe. Violence was metastasizing, and politicians like Wallace were at least tacitly encouraging it. So were politicians of a more conventional type who found more elegant words to express some of the same sentiments. For them, Wallace was a gift.

Barring a radical change, it was obvious by the spring of 1968 that Wallace would stay in and Richard Nixon would be the Republican nominee. But who would be his Democratic opponent?

For just a few days, April 1-3, the only announced candidates were Eugene McCarthy and Robert F. Kennedy. Those two men knew three big things. The first was that they had to win primaries to show their viability as national candidates. The second was that, no matter how many state primaries they won, the “system” wouldn’t make the results of those primaries dispositive—many did not award the winners pledged delegates, and others had favorite-son candidates who would be in Chicago to do some horse trading. In sum, the party bosses still controlled the nominating process. The third was that Hubert Humphrey, LBJ’s loyal-but-tormented Vice President, was going to jump in as soon as he thought it decent to do so. Humphrey was expected to “inherit” some of the bosses from Johnson, but because of his late entry, he wouldn’t be running at all in primaries. Humphrey’s candidacy would, in effect, run parallel to his rivals, amassing delegates through proxies and local powers, but without person-to-person, head-to-head contests.

For McCarthy and RFK, this left a very narrow lane to run in. They had to punch it out between themselves, a clear favorite had to emerge, demonstrating a popularity that was so great that the party bosses could not ignore it

RFK’s late announcement had caused him to miss filing deadlines, so, in April, McCarthy racked up large, pledged-delegate wins in Wisconsin and Massachusetts (yes, that Massachusetts). He also dominated in Pennsylvania’s beauty contest. But none of those, nor other states with nominating conventions carried the weight of Indiana, the first true head-to-head contest between the two men, scheduled for April 30, and an absolute must-have for Kennedy.

April 4 first found Kennedy campaigning at Ball State University in Muncie. He then got on a plane to Indianapolis, disembarking to the unthinkable: Martin Luther King had been assassinated. In a time before cell phones and 24/7 instant communication, news came on television and in the next day’s papers. None of the crowd there to greet him had any idea of the act of mindless violence that had just occurred.

Watch this extraordinary, essentially extemporaneous five minutes. I’m not going to describe it, because it speaks for itself, and Bobby’s words spoke to his audience. Cities across the county seethed, but Indianapolis did not. There, people drew back; they mourned, but they recoiled from further violence.

Baltimore was a different story. Violence began on the 6th and lasted through the 9th. The Maryland Governor called out the National Guard; thousands of arrests were made; six died. On April 11, he summoned 100 moderate Black leaders for what they thought would be a time for conciliation. Instead, Spiro Agnew laced into them, accusing them of cowardness and complicity. Overnight, Agnew became a folk hero to some on the Right, who were looking for a more close-fisted approach to Black protests. He also caught the attention of Richard Nixon, who would go on to build a part of his campaign around some of the issues that Wallace had raised.

April 27, Hubert Humphrey formally entered the race. With LBJ out, he became the heir to many of Johnson’s boss-controlled delegates, along with a chunk of organized Labor, and some Southern Democrats not ready to bolt to Wallace. Now hard numbers really mattered. Humphrey would almost certainly go into the Convention with more delegates, but could his first-ballot votes be kept below the level needed for the nomination? There were two avenues the McCarthy and RFK campaigns could take to deal with this before the Convention began—the first was working the nominally uncommitted delegates (more likely, the local powers who controlled those state delegations) to consider their man, or at least not to commit to Humphrey immediately. The second was to navigate the primary and caucus system to show strength, even if the “hard” results didn’t deliver any delegates at first. The fix may have been in for Humphrey, but the “fixers” were not exactly sentimentalists. They wanted to win. Show them that Humphrey was demonstrably weak, and an alternative would become possible.

It’s hard to characterize Humphrey fairly. Surely, he was hardworking, intelligent, occasionally eloquent, and above all a man of good intentions. But he was weighed down by two sets of factors—on style, his “Happy Warrior” affect seemed out of synch with the gravity of the issues. On substance, he was boxed in by the paradoxical LBJ demand that he embrace the very policies that were so unpopular they had forced the President from the race. It didn’t help that the acts of deference on which LBJ insisted, and which Humphrey gave, further diminished Humphrey in LBJ’s eyes. Johnson just didn’t think his Vice President could cut it. He froze him out of policy meetings and kept him on a tight leash, and the public knew it.

Still, Humphrey came out of the box fairly well. He had a strong team and knew how to be a wirepuller with the wirepullers. Although not actively on the ballot anywhere, several favorite-son surrogates worked his behalf—including in the delegate-rich states of Ohio, Florida, California, and Indiana. The (Democratic) public, while not particularly enthusiastic, was reasonably well disposed to him. A May 7 Gallup Poll had Humphrey at 40%, RFK at 31%, and McCarthy at 19%. He wasn’t going to be easy to take down. The message to the Kennedy and McCarthy camps was clear: there was majority support for a more liberal candidate, but one candidate, not two. Either the two men came to a rapprochement, as a ticket or with the “loser” in some other prominent position in a future Administration, or they continued the cage match. The problem was that neither wanted to yield.

Cage match it would be. On May 7, Bobby won the Indiana primary, with Richard Branigan, the favorite-son Governor and Humphrey surrogate finishing second, McCarthy a disappointing third. The next contested primary was Nebraska on May 14, and again Bobby beat McCarthy.

Inside the RFK campaign there was cautious optimism mixed with realism. Bobby’s strength with key portions of the Democratic base was elevating him into the “top challenger” spot. But they could also count, and McCarthy’s delegate count, while temporarily stalled, was still higher than theirs. Humphrey’s rose continuously through the miracle of party discipline amongst the insiders.

RFK also had another, self-imposed obstacle. He felt it was imperative not to lose a contested state, anywhere. Kennedy men (Jack, Bobby and Ted) had won 26 consecutive elections, and Bobby felt the record helped create an air of inevitability. A loss, he told both his team, and, rather clumsily, some in the media, could be a mortal blow to that image, and to his campaign generally.

And then, on May 28, he lost. Oregon, where McCarthy’s message resonated particularly well with primary voters (anti-war, educated, middle class, very demographically homogeneous) and where McCarthy was exceptionally well organized. RFK, for once, did not recognize the danger and did not have his top people in the state. And, he had baggage. Whereas Jack, in 1960, had no history and his extraordinary charisma, Bobby brought a troubled past with organized labor from his anti-corruption years in the Senate, and the sense that he’d entered opportunistically. His style and the portion of his central campaign message which included poverty and economic opportunity just didn’t connect.

In the give and take between the two men, Oregon was a clear shot in the arm for the McCarthy campaign, and he needed it. The truth was McCarthy had been losing altitude for some time. He had been having trouble raising money; his organization, at the national level, was fraying; and the head-to-head with Bobby was taking an emotional toll. Before March 16, McCarthy had been running a campaign above it all—he’d taken on a sitting President—indeed, he’d taken down a sitting President, but without being a target himself. Politics just isn’t like that, particularly when you approach the top. You can be aspirational, but you also need to be tough. The Kennedys knew how to throw and take an elbow; our two most graceful Presidents since 1968, Ronald Reagan and Barack Obama, knew how to; and Richard Nixon had made a career of it. McCarthy didn’t. He got angry when RFK called himself more electable, and he stayed angry. It filtered into seemingly every conversation about Kennedy, either private or with the press, took on an unpleasant edge, and almost certainly hurt the inspirational image McCarthy wanted to project. Bobby, realizing that he would need McCarthy supporters to defeat Humphrey, studiously did not react, but he kept notes (Kennedys always kept notes).

A bare week between Oregon and California. A week for McCarthy to feel renewed energy and for RFK to use every bit of his. Even though McCarthy was struggling, both men understood that the Kennedy campaign could not withstand another loss. There was also a lesson to be learned from Oregon—while California was an exceptionally diverse state, a good percentage of it consisted of people just like the ones who put McCarthy over the top in Oregon. Bobby’s strengths—inner cities, Caesar Chavez and his United Farmworkers, were formidable, but wouldn’t work everywhere. He and his team stretched themselves to a near-breaking point, but McCarthy was well-organized as well—and had an infusion of cash from an unlikely source—large Humphrey backers, with the blessing of Humphrey himself, who saw RFK as the bigger challenge. The two men conducted a largely desultory debate, which showed neither at his best.

June 3, the day before the primary. The “time for choosing” had come, probably none too soon. Kennedy was exhausted—his style of plunge-in-shake-hands campaigning had worn him down. He literally had to sit down at the edge of a stage in one venue. Besides California, a primary was also being held in South Dakota, and, while the number of delegates at stake were comparatively small, a loss would have taken some of the shine off of any positive California result.

South Dakota’s polls closed two hours earlier than California’s and Senator George McGovern called with good news—Bobby had won decisively. The Kennedy people waited for California. An early McCarthy edge faded away, and, as it seemed Bobby would win, talk again returned to wooing McCarthy with something to get him to drop out of the race. Humphrey, with his huge institutional advantage, was racking up delegates, and, without a clear single alternative, would be the safer bet for the bosses.

It was too early to declare victory, so Kennedy submitted to four interviews, and watched numbers come in. Finally, it was clear he had a decisive lead, maybe not as much as he wanted, but a clear win. He left his suite and headed to the ballroom. Cheers greeted him, and he made what would be considered a fairly unremarkable victory speech. He then left through the kitchen, walking and talking with a reporter.

A small man armed with a .22 caliber gun pushed forward and fired several shots. Sirhan Sirhan had seen on television Kennedy’s pro-Israel speech at a Portland synagogue, and he was filled with purposeful rage. He shot first at Kennedy, struck him at least twice, then emptied his gun at those nearby.

Robert F. Kennedy slumped to the ground, and for the second time in just two months, the country stopped to hold its breath. A little more than 24 hours later, he gave his last one.

There was a sense everywhere, in 1968, that things were giving. That man had not merely lost control of his history, but might never regain it.

Next, Nixon in Miami, and how Chicago, where things that were giving, gave.