by Rafaël Newman

I am not outside the language that structures me, but neither am I determined by the language that makes this ‘I’ possible. —Judith Butler

The force of recent attempts to increase minority visibility in the performing arts, principally in the US, by matching the identity of the performer with that of the role—in effect a form of affirmative action—has been diminished by a series of tabloid “scandals”: the casting of Jared Leto as a trans woman in Dallas Buyers Club criticized as “transmisogynistic”; the backlash against the non-Jewish Helen Mirren playing Golda Meir; or the foofaraw over Bradley Cooper’s prosthetic proboscis in Maestro. These attempts to increase minority visibility, no doubt well-meaning and long overdue, were taken ad absurdum with the Met’s 2019 choice of a Chinese soprano for the title role in Madama Butterfly, in a cringingly tone-deaf bid to make up for the tradition of Westerners singing the eponymous Japanese heroine.

The force of recent attempts to increase minority visibility in the performing arts, principally in the US, by matching the identity of the performer with that of the role—in effect a form of affirmative action—has been diminished by a series of tabloid “scandals”: the casting of Jared Leto as a trans woman in Dallas Buyers Club criticized as “transmisogynistic”; the backlash against the non-Jewish Helen Mirren playing Golda Meir; or the foofaraw over Bradley Cooper’s prosthetic proboscis in Maestro. These attempts to increase minority visibility, no doubt well-meaning and long overdue, were taken ad absurdum with the Met’s 2019 choice of a Chinese soprano for the title role in Madama Butterfly, in a cringingly tone-deaf bid to make up for the tradition of Westerners singing the eponymous Japanese heroine.

A salutary, if ironic corrective to this essentialism is offered by casting members of “minority” groups—the term is (mis)used advisedly to include women—explicitly against type: Denzel Washington as Macbeth, for instance, or Glenda Jackson as King Lear. Ironic, because such creative, intentional miscasting replicates the very misprision criticized on the part of the hegemon, which allegedly seeks to reserve privilege to its own replicants at the cost of the subaltern. The maneuver is salutary, however, both morally and aesthetically, because it proactively rights a wrong of exclusion, while opening up new avenues for the interpretation of established works of art. Once such a creatively “wrong” choice is made, in other words, and a given Western canonical work is no longer the account of a particular (most often white, cis-male, hetero) subject, it becomes—although the term is regularly subject to post-structuralist suspicion—universal. And finally, by playing the hegemon, the subaltern reveals the political and linguistic constructedness of that hegemon’s subject position.

These were among the thoughts that preoccupied me as I prepared for a house concert last month with my friends Annina Haug and Edward Rushton.

We had agreed, under the aegis of our association, Besuch der Lieder, to perform a selection of songs from Franz Schubert’s Winterreise cycle, at the home of the architect and painter Sophia Berdelis, my former neighbor and new-found friend: a selection, from among the 24 Lieder, or songs, comprised by the cycle, both because a complete recital would well exceed our typical hour-long performance time (including my comments) and tax the patience of Sophia’s cocktail party guests; and because Sophia’s daughter, herself an aspiring musician, had in fact only explicitly requested one of the songs by name (“Gefror’ne Tränen”, “Frozen Tears”).

As I began to write the exegetical remarks for the occasion I was thus confronted by a problem: how to speak about our relatively novel presentation of an established work to an audience which might have preconceptions about that work—or which might in fact have no familiarity with the classical tradition at all. In other words, how could I at one and the same time introduce them to a canonical work of art, while also acknowledging the extent to which we had tampered with it? And most crucially, how was I to address the elephant in the room: our creative miscasting of a female artist to sing what has traditionally been understood as a male role?

The “maleness” of Winterreise (Winter Journey) arises from two sources, its manifest textual content and its (dual) male authorship. Franz Schubert (1797-1828) set poems by Wilhelm Müller (1794-1827) to music in two stages during the last years of his short life, since Müller, who himself died young, had published the sequence in stages. Taken together, the 24 texts render an impressionistic account of a solo voyage, made during the winter months by a first-person narrator or “lyrical subject,” away from a life of social connection and towards an uncertain, solitary, death-tinged destination, perhaps in the wild or perhaps, as the final song enigmatically suggests, in the company of a destitute minstrel, leading a marginalized existence from village to village. From a few references, scattered here and there in the poems, it is possible to imagine the voice as that of a youngish man—indeed, given the historical realities of the period, it is difficult to think otherwise: a youngish man who had believed that he would perhaps marry the young woman with whom he had become involved, but had been obliged for some reason to leave her side. As for the “gendered” quality of the cycle’s authorship, the writer of the poems and the composer of the songs alike were young men at the time of creation, both biologically and politically speaking: young in years as well as in the Oedipal sense of rebels against the “old” order, the restoration reactionism of the Biedermeier, post-Napoleonic period.

Ian Bostridge, the tenor and social historian, in a magnificent book-length study of the cycle, takes up this political element and sketches the protagonist of the songs as a Rousseauian (and thus proto-revolutionary) anti-hero, the private house tutor of a well-to-do young lady whose romantic entanglement with his pupil has occasioned his departure. (For his part, the baritone Thomas Hampson likens Müller’s wanderer to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein ruefully pursuing his Creature, and thus similarly places him within an allegorical framework of revolution and reaction, if of less stable gender.) In addition to filling in other possible details of this protagonist’s experience, Bostridge notes that certain singers have deliberately waited until they were in middle age before attempting the cycle—which is nonsensical from a dramaturgical point of view, since there are as many references to the youth of the “narrative I” (Ich-Erzähler) as to “his” gender. But that gender—understood in its strictly grammatical sense, since German, like its ancient Indo-European forbears, is an inflected language, with grammatical gender marked at the level of the morpheme—is made explicit a total of merely five times, over the course of 24 texts, some with multiple strophes. Furthermore, of those five instances, four of them are in an oblique case—vocative or accusative—and just one in the nominative, the regular case of subjecthood: “I thought I was already an old man”. (Significantly, in German, only the masculine gender is explicitly inflected to mark its occupation of the objective position, by adding an -n suffix in the accusative, when the subject is acted upon rather than acting, while the feminine and neuter genders remain uninflected: as though their subjecthood always already comprised its own subjection.) The narrative voice thus largely refrains from identifying itself as (grammatically) masculine, and in those few instances when it does, this is accomplished by adopting the position of the Other, whether that is a linden tree it imagines calling out to, or an imaginary passerby (mis)identifying it as prematurely aged; while the object of its (failed) romantic attentions, the (putatively) young woman whose espousal it has been obliged to renounce, is frequently addressed in the diminutive, i.e. in the neuter gender, as “Liebchen” or “little love”—and thus sexually indeterminate, at least at the grammatical level.

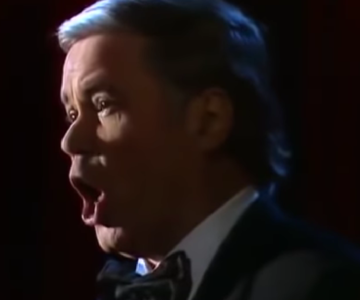

But such enactments of gender all occur in the linguistic dimension, as the (albeit discreet) index of Wilhelm Müller’s authorial intention. At the musical level there is less ambiguity, since Schubert composed the songs in a lower register (except for the last Lied, “Der Leiermann” [“The Hurdy-Gurdy Man”], which he had originally pitched higher, but which his publishers compelled him to transpose downwards, since it would otherwise have been too difficult for amateur musicians to sing, and thus hamper sales of the sheet music). And so canonical performances of the cycle, at least until quite recently, have been by male singers, chief among them by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, whose towering career in postwar Germany was centrally devoted to the resurrection and perfection of the Lieder form. Fischer-Dieskau recorded Winterreise many times; one mid-1980s performance, accompanied by Alfred Brendel, can be seen on video, and is a bravura example of minimalism: just the pianist stage left and the singer stage right. The camera occasionally focuses on Brendel’s hands, particularly in the intros to songs, but is trained for the most part on Fischer-Dieskau’s face in close-up, where every half-smile, grimace, and twitch of the eyebrows is keyed to the text. And although the baritone was by the time of the recording in his fifties, his studiedly subtle mimicry ably suggests the alternating naivety and bitterness of a young man disappointed by a cruel world.

Bostridge, only now reaching the age Fischer-Dieskau had attained in the 1980s, has also sung the cycle on many occasions—indeed, the subtitle of his book is Anatomy of an Obsession. In one notable production, filmed when he was in his early thirties, he stages the songs, true to his vision of the cycle as “the first concept album,” as a series of MTV-like music videos, united in (solo) cast and setting and largely symbolist in their sparing use of props. The camerawork is imaginative, on one notable occasion, during “Die Krähe” (“The Crow”), twirling into the air to make of the tenor, in his New Romantic overcoat, a doppelganger of the carrion bird he is addressing. For all its denaturing and the androgynous quality of Bostridge’s physical presentation, however, his performance remains resolutely masculine, in keeping with the tradition.

Nevertheless, in recent times, female singers, particularly mezzos, have performed transposed versions of the cycle, and have staged productions whose dramaturgy, rather than denying or downplaying its creative “re-gendering,” places it stage center. Brigitte Fassbaender’s 1995 film version, directed by Petr Weigl, while ambitious dramatically and cinematographically, is however a hot mess. Accompanied by Wolfram Rieger and inexplicably sporting a wimple, Fassbaender sings the Lieder from a sort of sanctuary-cum-atelier as Pasolini-esque softcore porn unfurls around her. The film features a bewildering cast of characters and multiple locations, including a decidedly non-desolate Prague, and resolutely eschews the few vivid objective correlatives in Müller’s text in favor of visual cues imported wholesale into the spare mise-en-scène implicit in the original. And just what an artistically inclined Mother Superior might have to do with Müller’s story is unclear.

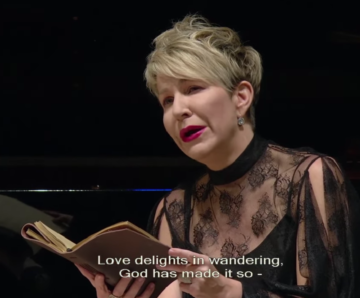

In her 2021 presentation of the cycle, Joyce DiDonato offers another solution to the gender “problem”: by staging herself as the narrator’s lost Liebchen—the Mädchen he might have married, but has had to leave—seated and reading letters (or diary entries?) from the wanderer as she pines for him, she effectively re-writes Winterreise as “fan fiction” à la Madeline Miller, whose Song of Achilles, for instance, gives an account of the hero’s wrath from the perspective of his belovèd Patroclus (as well as from that of his “trophy bride” Briseis). Meanwhile, in a live performance of the entire cycle by my friend and Besuch der Lieder colleague Jeannine Hirzel, also accompanied by Edward Rushton, a few years ago at a private venue in Zurich’s Old Town, the narrative gender question was more fluidly resolved: Jeannine, posed squarely before the piano and with her considerable dramatic talent to the fore, clad in modern, masculine dress and adopting a romantically virile stance, fairly belted out the songs in mezzo transposition.

Last month, at Sophia’s home in the Oberstrass district of Zurich, Annina chose to approach the dramaturgy of her Winterreise differently. She had selected the 12 songs she was to sing from the series of 24, and, in one or two instances, had slightly altered their canonical order, her decisions guided by a “gut feeling”. Her dress was understatedly, classically feminine, and she positioned herself to the side of the piano, rather than directly in front of it, which gave her delivery a discrete and pensive quality. Rather than enacting or mimicking the often highly sentimental, even adolescently pathetic scenes conjured up by Müller’s texts—hot tears melting ice, a crow circling over the head of a lone and moribund traveler, the wind stupidly flattering a fickle belovèd—Annina internalized the drama; furthermore, she sang the few overtly (mis)gendered passages naturalistically, without ironic emphasis. The effect was indeed to universalize the work, to detach it from its factual, historical, “real world” situation and to make of the sequence a meditation on mortality: on the “winter journey” of every viviparous being, whose life begins with a valediction (the first song in the cycle is entitled, counterintuitively, “Good Night”) and a departure, from the warm symbiosis of the womb into the hostile cold of a lonely existence. When Annina sang, in “Der Wegweiser” (“The Signpost”), “eine Straße muß ich gehen, / die noch keiner ging zurück”—I must travel down a road upon which none has yet returned—the text was heightened, from the particular experience of a lone wanderer to a generalized account of the unidirectional nature of organic life.

And when she came at last to “Der Leiermann” (“The Hurdy-Gurdy Man”), the last Lied in the cycle, in Müller’s, Schubert’s, and her own arrangement, Annina sang it accompanied by Edward in the higher key originally intended by the composer, which made the song even more jarringly uncanny than it would have been, sung, as is traditional, in the same key as the penultimate Lied. Annina’s meeting with the ghostly itinerant musician, turning the handle on his poor instrument just outside the bounds of civilization, became a disturbing encounter with the possibilities of identification, with the limits of human existence, as the singer is left at the end of the cycle suspended between continuing on a solitary, death-bound path, or choosing sociability, however impoverished. And the fact that Annina was stationed during her performance, given the layout of Sophia’s apartment, before a doorway leading from the salon into the corridor, rendered the existential stakes of the cycle palpably visible: like the petitioner in Kafka’s fable, she stood “Before the Law,” at the threshold of an allegedly free choice, whose conditions, however, had been shaped by forces outside herself.

*

At a day-long conference on inclusive language held by ASTTI, the Swiss Association of Translators, Terminologists and Interpreters in Bern in 2021, a representative of the Swiss Federal Chancellery presented the reasoning behind the recent decision to prohibit the use of the so-called Gendersternchen (“gender star”) in top-level government communications. The gender star—an asterisk (*) deployed both to acknowledge and to absorb gender difference at the grammatical level in German nouns (e.g., Student*innen = both male and female students)—has been in use in German-speaking countries for the past decade and has, predictably, become the object of pedantic criticism and political reaction. The Chancellery’s decision, while no doubt made in awareness of the technique’s controversial potential, does not thereby preclude such typographical reform: its representative justified it rationally by the inability of automatic voice programs to make the asterisk audible for sight-impaired users of the official website, and noted that the Chancellery had opted for other methods (an internal capital or an underscore) to render its language gender inclusive—at least in German: Switzerland’s official Romance tongues are proving less receptive to modernization.

The gender star’s force thus comes at once from the high (and highly contested) visibility it grants the “fact” of linguistic genderedness, which may or may not adequately represent the (changing) “reality” of “actual” human gender, and from its refusal to submit to the regime of spoken speech, with all of that technique’s supposed power and preeminence over written language. The gender star serves as a hinge: a technology that simultaneously separates and joins non-identical elements that are nonetheless expected to operate in tandem, and which marks the location of difference, between an inside and an outside, the open and the closed, two homologous “natural” spaces rendered distinct by the cultural intrusion of a door. It also holds out the possibility of a third—of at least one other position, on a spectrum that is currently in open-ended continuation.

The elements at play in Winterreise do indeed include the “masculine” and the “feminine” positions, at the grammatical, textual, and musical levels. Above and beyond and below these “differences,” however, subtending them, as it were, ideologically, is the interaction of the (allegedly distinct) realms of the natural and the cultural. Winter stands for the first-order chaos system known as “the climate,” the natural world, to which we are all intimately subject and which can decide whether we live or die, but which, unlike a second-order chaos system such as the financial markets, is perfectly indifferent to the information we provide. (That is, at least according to a certain reactionary political framing.) Reise, meanwhile, “the journey,” constitutes the intrusion, into this indifferent system, of the human or cultural; of signification and difference; of the measurement of distance over time, the construction of an origin and a destination, the division of individual from community, the oscillation from da to fort. The imposition of a measured human scale onto a limitless natural habitat. This is made marvelously explicit in the shortest and wildest of the songs in Winterreise, “Der stürmische Morgen” (“The Stormy Morning”), a triumph of the pathetic fallacy (here in William Mann’s English translation):

How the storm has torn

the grey mantle of heaven!

The wisps of cloud flutter

about, jostling feebly.

And tongues of red fire

flicker among them.

I reckon this a morning

to match my frame of mind!

My heart sees in the sky

its own painted portrait.

It is nothing but winter,

winter chill and savage.

When marked with the hinge of an asterisk, the conjunction of these two elements—Winter*reise—renders visible what is audible in Schubert’s settings of Müller’s poems, and in Annina’s performance of them: that human life is the site of a tension between the insensible conditions of its general, organic emergence, and the will to impose particular meanings on its individual experience.

Of course, as we are currently reminded, the imposition of a particular cultural meaning on the natural world is not necessarily bounded by individual experience, but may propagate throughout an entire community in the form of ethnonationalist politics, territorial aggression, and war. In his excellent lectures on the history of Ukraine, Timothy Snyder recalls the mediaeval sense of the word Reise, which for the Teutonic Knights, among other fervent Christians, meant a crusade of occupation and conversion by violence: their colonial expansion eastward was instrumental in the forming of the early modern Ukrainian state. Muscovy’s modern crusade westward, now still underway, marks yet another chapter in a long and terrible chronicle. It can only be hoped that this Reise is halted by a Winter hostile to human cultural projects, both personal and national. And that our ongoing, disastrous intrusion into the ostensibly immutable chaos system that is our climate may be halted in its turn as well, before we all find ourselves, in Müller’s words, traveling down a road upon which none has yet returned.