by Michael Liss

There was a sense everywhere, in 1968, that things were giving. That man had not merely lost control of his history, but might never regain it. —Garry Wills, Nixon Agonistes: The Crisis of the Self-Made Man

Last month, I wrote about Eugene McCarthy’s Vietnam-based primary challenge to Lyndon Baines Johnson’s reelection campaign, the angst-ridden mid-March entry into the race by Robert F. Kennedy, and LBJ’s stunning withdrawal on March 31, 1968. I ended with April 4, when the “Dreamer,” Martin Luther King, was assassinated.

Some of the chaos that ensued is the subject of this piece. “Things were giving,” seemingly everywhere, and all at the same time. America’s ability to deflect the course of history as it accelerated toward the unknown was disappearing. The months that followed the King assassination were punctuated by more violence, more uncertainty, and the continued deterioration of social discourse.

None of this appeared out of thin air. Grassroots efforts on Vietnam and on civil rights had been intensifying for years, as had been the backlash to those movements. FDR’s New Deal coalition was fraying, most notably in the South, but also in the industrial Midwest. 1968 was also to be the last stand of the “Liberal” Republicans, people like Nelson Rockefeller, Charles Percy, and John Lindsay. We think about them and their ambitions with an amused raised eyebrow, but, at the time, they were men of reputation and influence.

There were so many crosscurrents, so many strange alliances, that it’s difficult to trace each causation, but if you want to pick up on an organizing thread other than Vietnam, look to George Wallace. History frames Wallace largely as the segregationist that he was (after losing his first run for office for being more moderate than his opponent, he vowed “never to be out-n…ed again”). It sometimes skips over how Wallace had a broader message, anchored by the emotional appeal of his racism, but also including perennial themes of law and order and economic and social grievances that resonated in people’s lives. Read more »

The force of recent attempts to increase minority visibility in the performing arts, principally in the US, by matching the identity of the performer with that of the role—in effect a form of affirmative action—has been diminished by a series of tabloid “scandals”: the casting of Jared Leto as a trans woman in Dallas Buyers Club

The force of recent attempts to increase minority visibility in the performing arts, principally in the US, by matching the identity of the performer with that of the role—in effect a form of affirmative action—has been diminished by a series of tabloid “scandals”: the casting of Jared Leto as a trans woman in Dallas Buyers Club  1.

1. Jeannette Ehlers. Black Bullets, 2012.

Jeannette Ehlers. Black Bullets, 2012. How plastic – really plastic – gelatin presents as a food. Not only in the “easily molded” sense of a pliable art material but also its transparency. Walnuts and celery, the “nuts and bolts” of gelatin desserts, defy gravity, floating amidst the cheerful jewel-like plastic-looking splendor of the 1950’s, when gelatin was the king of desserts. Gelatin’s mid-century elegance belies its orgiastic sweetness, especially the lime flavor, which is downright otherworldly. If you stir it up hot, half diluted, gelatin lives up to its derelict reputation with regard to the sickbed and sugar, being thick and warm, twice as intoxicatingly sweet, and surely terrible for an invalid’s teeth, if not metabolism. In my novel, Dog on Fire, I hypothesize that lime-flavored gelatin is the perfect murder weapon.

How plastic – really plastic – gelatin presents as a food. Not only in the “easily molded” sense of a pliable art material but also its transparency. Walnuts and celery, the “nuts and bolts” of gelatin desserts, defy gravity, floating amidst the cheerful jewel-like plastic-looking splendor of the 1950’s, when gelatin was the king of desserts. Gelatin’s mid-century elegance belies its orgiastic sweetness, especially the lime flavor, which is downright otherworldly. If you stir it up hot, half diluted, gelatin lives up to its derelict reputation with regard to the sickbed and sugar, being thick and warm, twice as intoxicatingly sweet, and surely terrible for an invalid’s teeth, if not metabolism. In my novel, Dog on Fire, I hypothesize that lime-flavored gelatin is the perfect murder weapon.

Barring that reality, and knowing this would be an ongoing, lifelong issue, I got a tattoo on my Visa-paying forearm to remind myself that my actions affect the entire world. I borrowed Matisse’s

Barring that reality, and knowing this would be an ongoing, lifelong issue, I got a tattoo on my Visa-paying forearm to remind myself that my actions affect the entire world. I borrowed Matisse’s

I am sitting on the couch of our discontent. The Robot Overlords™ are circling. Shall we fight them, as would a sassy little girl and her aging, unshaven action star caretaker in the Hollywood rendition of our feel good dystopian future? Shall we clamp our hands over our ears, shut our eyes, and yell “Nah! Nah! Nah! Nah! Nah!”? Shall we bow down and let the late stage digital revolution wash over us, quietly and obediently resigning ourselves to all that comes next, whether or not includes us?

I am sitting on the couch of our discontent. The Robot Overlords™ are circling. Shall we fight them, as would a sassy little girl and her aging, unshaven action star caretaker in the Hollywood rendition of our feel good dystopian future? Shall we clamp our hands over our ears, shut our eyes, and yell “Nah! Nah! Nah! Nah! Nah!”? Shall we bow down and let the late stage digital revolution wash over us, quietly and obediently resigning ourselves to all that comes next, whether or not includes us? I first became aware of Miriam Lipschutz Yevick through my interest in human perception and thought. I believed that her 1975 paper,

I first became aware of Miriam Lipschutz Yevick through my interest in human perception and thought. I believed that her 1975 paper,

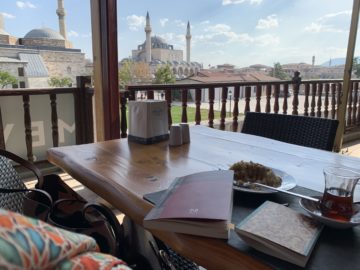

At dusk, the shaft of light striking Rumi’s tomb is emollient as pale jade. It has been a long, hot day in Konya, I’ve been writing in a café-terrace overlooking the famed white and turquoise structure of the tomb-museum complex. I sip my tea slowly, facing the spare, elegant geometry of the building that appears as a simple, intimate inscription on the vast blue. For once I am studying Rumi’s verses in Persian, not repeating English translations or paraphrasing in Urdu. “Bash cho Shatranj rawan, khamush o khud jumla zaban,” “Walk like a chess piece, silently, become eloquence itself!” I’m reciting to myself in the din, in awe of the kind of magnetism that would pull one as a chess piece. Only the heart understands this logic, not any heart, but the one that has been broken open, the one that is led to the mystery in cogent silence.

At dusk, the shaft of light striking Rumi’s tomb is emollient as pale jade. It has been a long, hot day in Konya, I’ve been writing in a café-terrace overlooking the famed white and turquoise structure of the tomb-museum complex. I sip my tea slowly, facing the spare, elegant geometry of the building that appears as a simple, intimate inscription on the vast blue. For once I am studying Rumi’s verses in Persian, not repeating English translations or paraphrasing in Urdu. “Bash cho Shatranj rawan, khamush o khud jumla zaban,” “Walk like a chess piece, silently, become eloquence itself!” I’m reciting to myself in the din, in awe of the kind of magnetism that would pull one as a chess piece. Only the heart understands this logic, not any heart, but the one that has been broken open, the one that is led to the mystery in cogent silence.

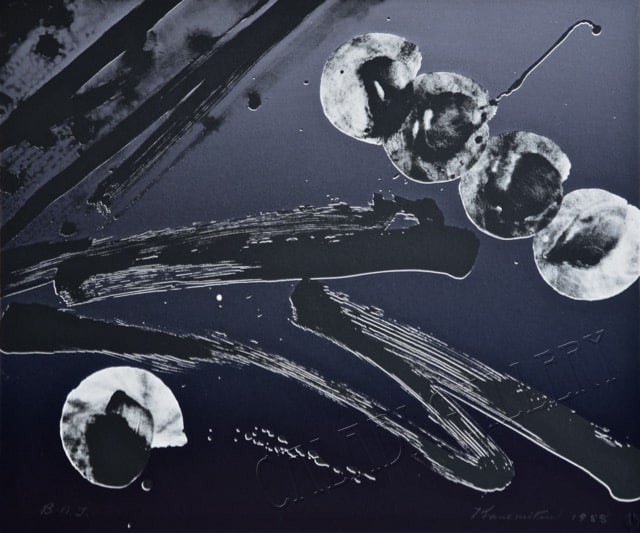

Matsumi Kanemitsu. For The Dream, 1988.

Matsumi Kanemitsu. For The Dream, 1988. “This is the story of a man. Not rich and powerful, not a big man like your father, Sweetheart. Just a funny little man. I didn’t know him long, only three nights. But there was something about him, something magical.” If “Rumpelstiltskin” started with this framing, we would have a different picture of the story’s meaning, a truer picture, for this framing suggests what is hidden below the surface.

“This is the story of a man. Not rich and powerful, not a big man like your father, Sweetheart. Just a funny little man. I didn’t know him long, only three nights. But there was something about him, something magical.” If “Rumpelstiltskin” started with this framing, we would have a different picture of the story’s meaning, a truer picture, for this framing suggests what is hidden below the surface.