by Jeroen Bouterse

On November 22nd, a far-right party received almost a quarter of the vote in the Dutch national elections, making it by far the largest of the fifteen parties elected to our new Parliament. Whether it will actually get to govern depends on its capacity to form a coalition, but what is certain is that it will take 37 out of 150 seats in the legislature this week; twelve more than the second-largest party.

International media reporting on this landslide all noted what the party and its leader Geert Wilders represented over the last decades: his aggressive attacks on Islam and his slurs on minorities with Islamic country backgrounds, his softness on Putin’s Russia, his resistance to climate measures, and his calls for a ‘Nexit’, to name a few. While Dutch media and (to-be) opposition parties have certainly not ignored these points, they barely played a role in the campaign, and in the initial domestic interpretation of Wilders’ victory.

In that interpretation, the vote for Wilders has to be understood as an anti-establishment vote: the result of general dissatisfaction with a centrist coalition failing to address the problems of the people. The far right won not because of its promises to close mosques, arrange “fewer Moroccans”, cut support to Ukraine, withdraw from the Paris agreement and quit the EU, but more or less in spite of those promises; it won, rather, because of social issues such as a persistent housing crisis.

I will push back against this interpretation later, because I believe it lets the voter off the hook too easily. Aspects of it are clearly true, however. Read more »

Will re-branding Covid help people start acting to protect themselves from it? Maybe we need an ad campaign to kick-start public health. Outside of judicial rulings and before marketing, we had religious leaders to remind us to the best ways to survive, and before that we had stories passed down for generations to help keep children safe from harm by altering their behaviour,

Will re-branding Covid help people start acting to protect themselves from it? Maybe we need an ad campaign to kick-start public health. Outside of judicial rulings and before marketing, we had religious leaders to remind us to the best ways to survive, and before that we had stories passed down for generations to help keep children safe from harm by altering their behaviour,

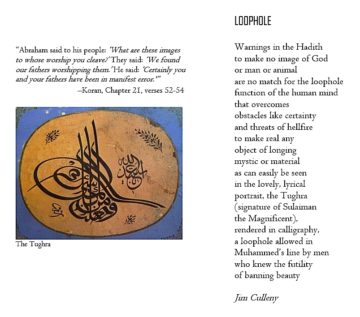

Masjid Al Aqsa, or The Far Mosque of Jerusalem, as the Quran calls it, is emblematic of the spirit of compassion and transcendence for Mevlana Rumi. “A heart sanctuary,” in the words of Rumi in his poem “The Far Mosque,” Al Aqsa represents a conquest over the egoistical desires of dominance, greed, vanity, violence and supremacy. It is held together by the sacred energy of merciful love, even “the carpet bows to the broom/the door knocker and the door swing together/like musicians.”

Masjid Al Aqsa, or The Far Mosque of Jerusalem, as the Quran calls it, is emblematic of the spirit of compassion and transcendence for Mevlana Rumi. “A heart sanctuary,” in the words of Rumi in his poem “The Far Mosque,” Al Aqsa represents a conquest over the egoistical desires of dominance, greed, vanity, violence and supremacy. It is held together by the sacred energy of merciful love, even “the carpet bows to the broom/the door knocker and the door swing together/like musicians.”

In 2016,

In 2016,

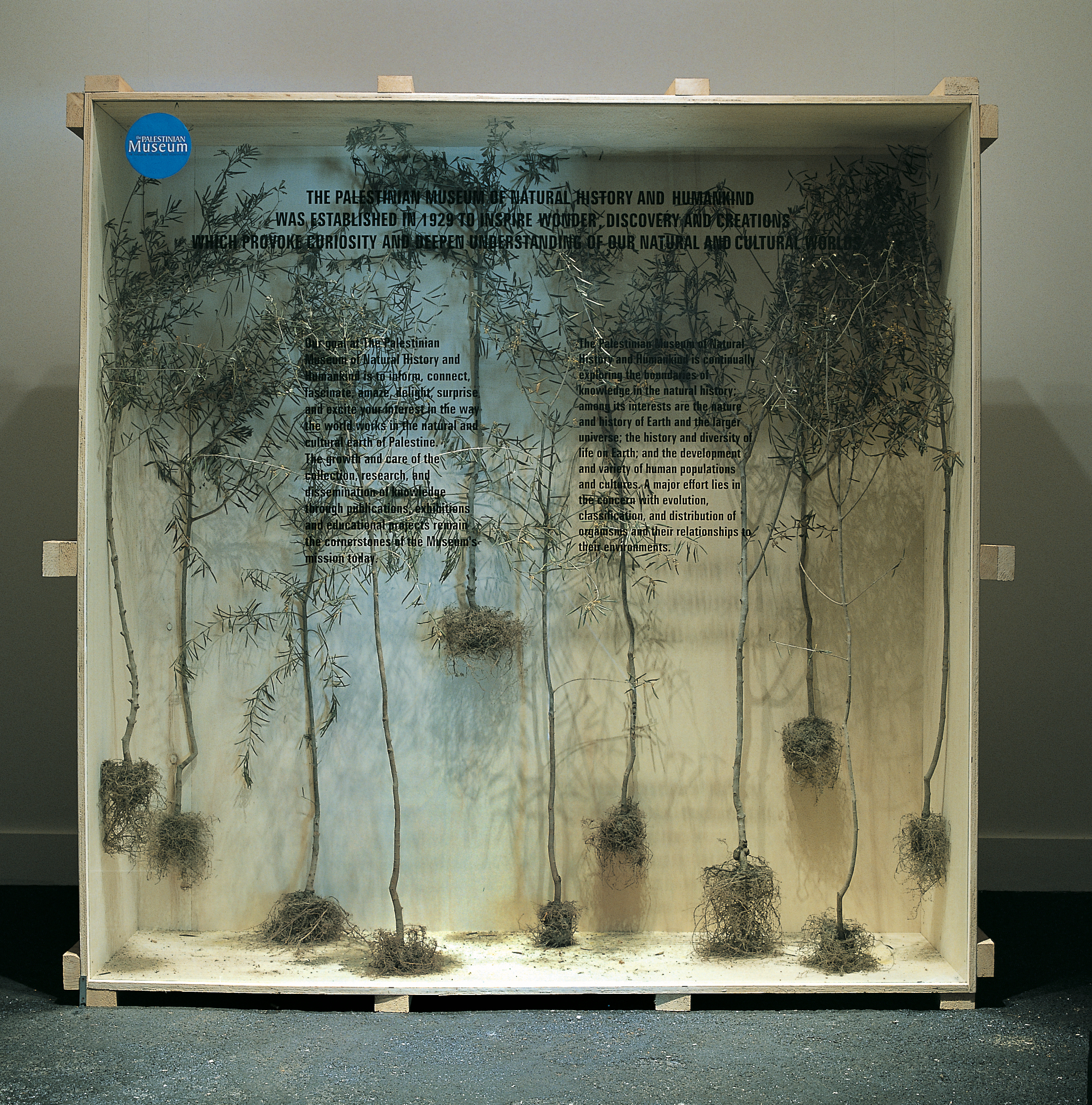

Khalil Rabah. About The Museum, 2004.

Khalil Rabah. About The Museum, 2004.

If a city could be an organism, then Kherson in Eastern Ukraine would be a sick body. For eight months, between March and November 2022, Kherson was occupied by Russian forces. Kidnapping, torture, and murder – in terms of violence and cruelty, Kherson’s citizens have seen it all. Today, even though liberated, the port city on the Dnieper River and the Black Sea is still being regularly bombarded: a children’s hospital, a bus stop, a supermarket. Even though freed, how could this city ever heal?

If a city could be an organism, then Kherson in Eastern Ukraine would be a sick body. For eight months, between March and November 2022, Kherson was occupied by Russian forces. Kidnapping, torture, and murder – in terms of violence and cruelty, Kherson’s citizens have seen it all. Today, even though liberated, the port city on the Dnieper River and the Black Sea is still being regularly bombarded: a children’s hospital, a bus stop, a supermarket. Even though freed, how could this city ever heal?