by Rebecca Baumgartner

During the recent Christmas shopping rush, I had to park at the very back of a crowded Target parking lot. By the time I trekked across the lot and reached the door of the store, my knees felt a bit achy. Not a big deal. After about half an hour of walking around shopping, I was extremely tired, limping slightly, and desperately needed to sit down.

By the time I was halfway through the parking lot heading back to my car, I was hobbling and leaning heavily on my cart as a makeshift walker. With every step, something in my knees ground against something else that wasn’t giving way, like there were too many bones fighting for space in there, or as though my kneecap were being polished like a gemstone in a tumbler.

I’d recently been diagnosed with osteoarthritis in my knees, after more than a year of writing off the gemstone-in-a-tumbler feeling as a normal part of aging. In the Target parking lot, as I limped past the parking spaces designated for people with disabilities, I allowed myself to think for the first time, “Maybe I would not be feeling this bad if I had been able to park there.”

It appeared to me that this was a very straightforward problem with a clear solution, thanks to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990: I could apply for a special parking placard that would let me park in one of the handicapped spaces every business is required to have.

I got home, medicated myself, and googled the application form for my state. Turns out this is a very simple form that merely requires a doctor’s signature. But what I soon discovered is that when a doctor diagnoses you with a degenerative disease, they are certainly happy to show you pictures demonstrating how messed up your bones are, prescribe you pain medication, and perform expensive surgeries on you – but they’ll be damned if they’ll sign a handicapped placard form for you. Read more »

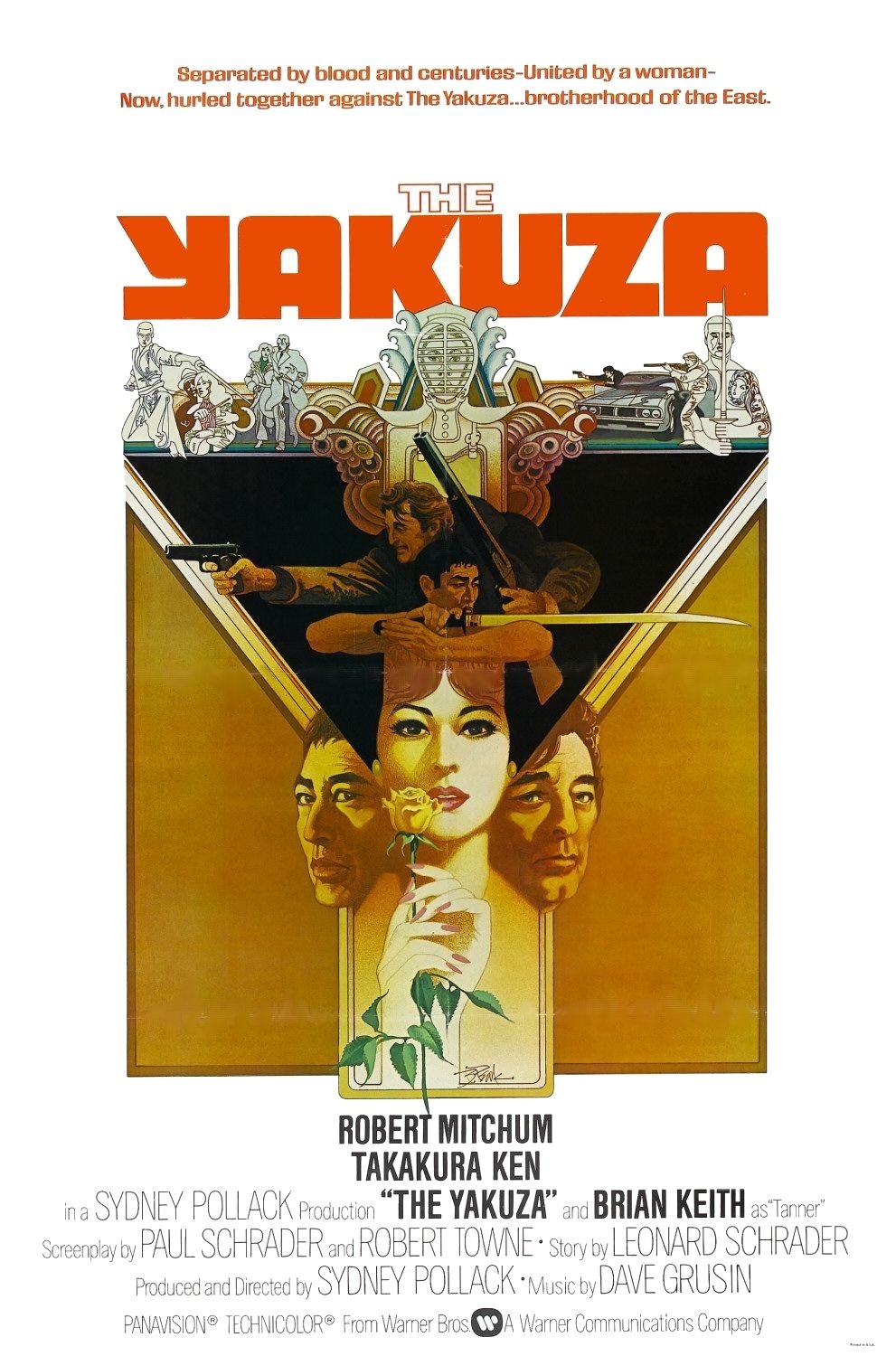

A few days ago I watched The Yakuza (1974), Paul Schrader’s screenwriting debut, and the following day I saw Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (1983) at the cinema. These two films would never feature on a double bill together, and yet, due to having watched them within 24 hours of each other, they seem related in my mind, and I can’t help but interpret Nostalghia in light of The Yakuza.

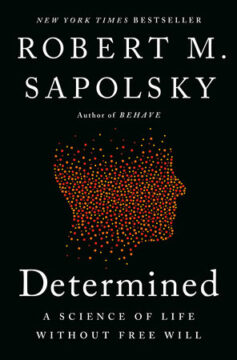

A few days ago I watched The Yakuza (1974), Paul Schrader’s screenwriting debut, and the following day I saw Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (1983) at the cinema. These two films would never feature on a double bill together, and yet, due to having watched them within 24 hours of each other, they seem related in my mind, and I can’t help but interpret Nostalghia in light of The Yakuza. A few months ago, the Stanford biologist Robert Sapolsky released

A few months ago, the Stanford biologist Robert Sapolsky released

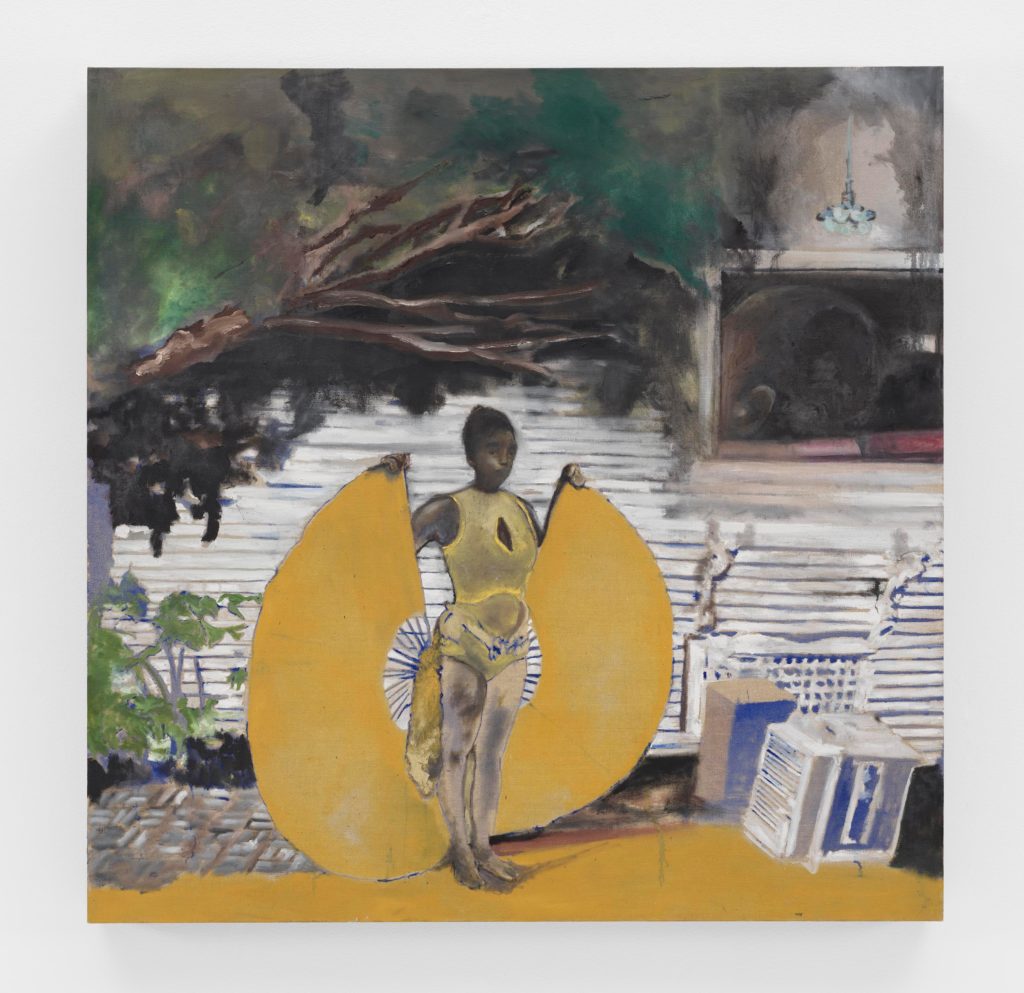

Noah Davis. Isis, 2009.

Noah Davis. Isis, 2009.

What do we know about vampires?

What do we know about vampires?

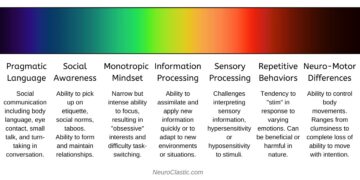

There are a few ideas I’ve seen floating around on social media about people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) having no empathy, no Theory of Mind, and being in need of

There are a few ideas I’ve seen floating around on social media about people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) having no empathy, no Theory of Mind, and being in need of  What is ASD? C.L. Lynch at

What is ASD? C.L. Lynch at  I read a great deal of Bertrand Russell when I was in my teens. I read various collections of essays, such as Why I Am Not A Christian, In Praise of Idleness and Other Essays, and Marriage and Morals, some of which my father had stored in a box in the basement, along with Orwell’s 1984, Huxley’s Brave New World, a book or two by this guy named Freud, though I forget which one, and some others. I also Russell’s – dare I say it? – magisterial

I read a great deal of Bertrand Russell when I was in my teens. I read various collections of essays, such as Why I Am Not A Christian, In Praise of Idleness and Other Essays, and Marriage and Morals, some of which my father had stored in a box in the basement, along with Orwell’s 1984, Huxley’s Brave New World, a book or two by this guy named Freud, though I forget which one, and some others. I also Russell’s – dare I say it? – magisterial