by Marie Snyder

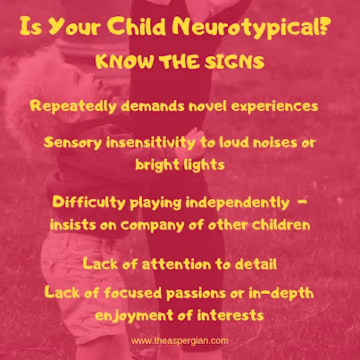

There are a few ideas I’ve seen floating around on social media about people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) having no empathy, no Theory of Mind, and being in need of fixing instead of accommodating. I just ignored them. But then I heard similar statements in a university class with controversial Autism Speaks and Hopebridge videos on the curriculum. I relayed my concerns about promoting only these organizations without explanation of current concerns and without providing other perspectives like from the National Autistic Society or Autistic Self Advocacy Network. This is a bit of a take-down on what appears to be an accepted curriculum around autism.

There are a few ideas I’ve seen floating around on social media about people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) having no empathy, no Theory of Mind, and being in need of fixing instead of accommodating. I just ignored them. But then I heard similar statements in a university class with controversial Autism Speaks and Hopebridge videos on the curriculum. I relayed my concerns about promoting only these organizations without explanation of current concerns and without providing other perspectives like from the National Autistic Society or Autistic Self Advocacy Network. This is a bit of a take-down on what appears to be an accepted curriculum around autism.

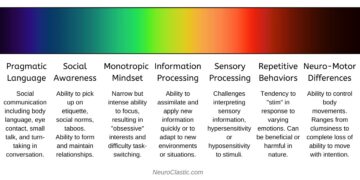

What is ASD? C.L. Lynch at NeuroClastic explains the spectrum really well using this illustration. You need to be affected in several of these areas regularly to be on the spectrum, and every person’s different. It’s complex. I went so far as to craft an assessment, the AQ-27, not remotely peer reviewed but rooted in the DSM-5, after being absolutely floored by the offensiveness or inaccuracy of the official assessments we had to learn in class.

What is ASD? C.L. Lynch at NeuroClastic explains the spectrum really well using this illustration. You need to be affected in several of these areas regularly to be on the spectrum, and every person’s different. It’s complex. I went so far as to craft an assessment, the AQ-27, not remotely peer reviewed but rooted in the DSM-5, after being absolutely floored by the offensiveness or inaccuracy of the official assessments we had to learn in class.

The Controversy:

Some advocates are “furious over the tone of the [Autism Speaks] video. ‘We don’t want to be portrayed as burdens or objects of fear and pity.” Hopebridge suffered scandals when an employee was fired for reporting an abusive incident with accounts of “undertrained staff and high turnover, a lack of transparency and accountability, and practices that prioritize profit over the needs and safety of young people with autism.” Some implications that people with ASD require lifelong care have been questioned since original stats were based on studies of children in psychiatric wards: “This potential bias means that we still know relatively little about the achievements of individuals in whom the presentation of early symptoms is more subtle.”

Scrutinizing the Claims of a Lack of Theory of Mind (ToM) in ASD

About 40 years ago a study was done that compared 20 kids with ASD, 14 with Down’s Syndrome, and 27 neurotypical (NT) kids on their Theory of Mind capabilities using a false belief test. Kids are shown a scenario with two puppets, Sally and Anne: Sally puts a marble in a basket and leaves the room; Anne moves the marble into a box instead, and then Sally returns. The kids are asked where Sally thinks the marble is. All of the NT kids picked the basket, but 16 of the 20 kids with ASD picked the box instead of the basket. However, the mean IQ of the kids on the spectrum in this sample was 82, which is below average. The study was more recently scrutinized by Atsushi Senju:

“It is possible that despite having the capacity to represent another person’s mental state, children fail the standard false belief test because of a weaker cognitive control or difficulty in pragmatic understanding. Secondly, individuals with ASD with higher verbal skills do pass the standard false belief tests.”

Senju’s analysis went on to explain that people with ASD can have difficulties in understanding non-literal utterances or inferring mental states from photographs of eyes, but those are typical ASD traits, not ToM traits.

Other tests indicating a lack of Theory of Mind in ASD are highly questionable, like looking for eye contact tracking to acknowledge anticipating actions, ignoring that some people on the spectrum use their ears more than their eyes or that they explicitly don’t look at people yet can still understand their different perspective. Another study had people close their eyes and relax for five minutes, and asked what they thought about, concluding that people on the spectrum don’t have ToM because they think about people slightly less than neurotypicals! A well-used ToM assessment has many questions that appear to test specifically for ASD and not ToM. Examples include questions around idioms, time passing, and recognizing facial expression and tone. Of 60 questions, only 17 seem specifically related to understanding that people’s behaviour is a function of their internal subjective mental states that can be different from our own.

One study, from Morton Ann Gernsbacher and Melanie Yergeau, questions the entire connection between ToM and ASD:

“The claim that autistic people lack a theory of mind—that they fail to understand that other people have a mind or that they themselves have a mind—pervades psychology. This article . . . documents multiple instances in which the various theory-of-mind tasks fail to relate to each other and fail to account for autistic traits, social interaction, and empathy; . . . and concludes that the claim that autistic people lack a theory of mind is empirically questionable and societally harmful.”

It’s curious, and potentially harmful, that one very small and contentious study from 40 years ago continues to be so influential and to override contrary studies that have appeared since then, even in programs geared to burgeoning therapists, enabling this error to be replicated.

ASD and 2SLGBTQIA+ Overlap

Another place this Theory of Mind topic comes up is in discussions of the overlap between the ASD and 2SLGBTQIA+ communities. Some go so far to suggest that there are a disproportionate number of Trans people who have ASD because they just don’t know themselves very well. However, this overlap between ASD and 2SLGBTQIA+ populations has been discussed in one study as possibly being due to neurodiverse people being more their authentic selves than neurotypicals: “Autistic individuals may conform less to societal norms compared to non-autistic individuals, which may partly explain why a greater number of autistic individuals identify outside the stereotypical gender binary.” Another study concluded, “Autistic individuals may have been more candid about their experiences than others due to differences in communication style and/or lessened concerns about adherence to social norms.”

On ASD and Empathy

Some older studies suggest people with ASD have little capacity for empathy, but looking at MRIs of people on the spectrum shows “heightened empathetic arousal” indicating a significant internal reaction to suffering, despite little external response in people on the spectrum. Another study suggested that instead of lacking empathy, people with ASD have an “imbalance in empathy skills” or “empathic disequilibrium” compared to NTs, specifically, a difference in the ability to recognize what another person is thinking or feeling and the ability to respond to someone with an appropriate emotion in equal measure. So, some express much more than they feel, and others express much less than they feel, but they all are able to experience empathy. Finally, another study suggests neurodiverse people communicate differently than neurotypical people, but can communicate well within the ND community: ” Many autistic people are motivated to have friends, relationships and close family bonds. . . . Participants identified that they often felt they were better understood by other autistic people.” This gives credence to the idea that, at least for people with ASD needing level 1 support, it’s a difference that isn’t necessarily disabling in the right environment. Other studies have found that merely providing clear and explicit instructions before tasks with mixed groups can make a huge difference in the involvement of students with ASD. One researcher said: “When autistic people joined the psychology profession in the 80s to better understand themselves and fellow autists, they pointed out that we don’t have a lack of empathy; we have so much of it that we feel overwhelmed.”

ASD and Bullying

It’s vital to dismantle these stereotypes of people on the spectrum being a burden to parents, being unable to understand other people, and completely lacking empathy because people on the spectrum already face abuse from adults and peers just from looking a little bit different. One study found that first impressions of people with ASD are far less favourable compared to NTs, and most people don’t want to talk to them. They filmed a variety of people, some with ASD level 1, and some neurotypical in a 60 second mock audition. Study participants were to rate each person on a variety of traits including likeability, intelligence, attractiveness, and trustworthiness. The participants either had audio only, visual only, audio-visual, a static image, or a transcript. Only in the transcript option were people with ASD rated as highly as NTs. The study commented, “These patterns are remarkably robust, occur within seconds, do not change with increased exposure, and persist across both child and adult age groups.” The fact that it doesn’t happen with written work means the negative judgment is about “style, not substance.”

Another study had NT adults rate videotapes of interviews: half of the interviews were of people with ASD and half NT. The participants indicated their interest in interacting with them in the future. The treatment/control in this one: half the participants were told about the ASD diagnosis of those specific interviews, and the other half just watched them all without this knowledge. Their finding was similar to the previous study when people weren’t told of the diagnosis, BUT first impressions improved when NT adults were made aware that the candidates had ASD. What isn’t clear is if the NT participants assessing them said they would be willing to hang out with them out of a sense that they would enjoy their company or from a do-gooder sense of pity that can sometimes lead people to talk to people on the spectrum as if they’re younger or less competent than they are.

Another study had NT adults rate videotapes of interviews: half of the interviews were of people with ASD and half NT. The participants indicated their interest in interacting with them in the future. The treatment/control in this one: half the participants were told about the ASD diagnosis of those specific interviews, and the other half just watched them all without this knowledge. Their finding was similar to the previous study when people weren’t told of the diagnosis, BUT first impressions improved when NT adults were made aware that the candidates had ASD. What isn’t clear is if the NT participants assessing them said they would be willing to hang out with them out of a sense that they would enjoy their company or from a do-gooder sense of pity that can sometimes lead people to talk to people on the spectrum as if they’re younger or less competent than they are.

Finally, Ruth Grossman showed NT people videos of children with and without autism, and it only took one second of tape to realize something was different about the ASD kids. She tried to find the specific movements and gestures that were the give-aways by using motion-capture technology, and found slightly less symmetry in facial expressions that’s just enough to cue others to a difference. She’s currently studying the timing of words and gestures as well.

On Encouraging ND Masking:

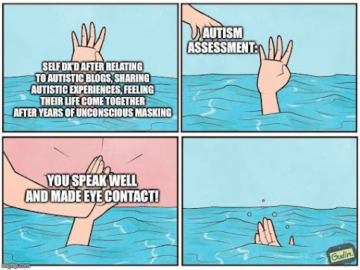

For decades many people thought that only children have autism largely because many children learn to mask over time to hide any unwelcome behaviours ,which can make it appear that the autism just went away. The textbook for one of my courses puts ASD and ADHD under “Disorders Among Children and Adolescents.” Because of masking, it used to be thought that some people outgrow autism and ADHD.

This type of masking makes some people wonder, ‘If people on the spectrum can act neurotypically, why don’t they just act like that all the time?’ In other words, what’s the difference between being socialized to behave in certain ways and encouraging masking to get neurodiverse people to behave more like neurotypical people in order to make their lives easier by helping them to fit in with others?

The problem is that for ND kids, masking doesn’t turn into natural behaviour. It doesn’t stick. For instance a NT child can learn to wait their turn in line by standing still and quietly through gentle reminders or some rewards, but for some kids who are ND, they might, for example, hand flap or pace or otherwise wiggle about. It’s not that they can’t wait patiently, it’s that this is how they wait patiently. For them to be perfectly still would take an inordinate amount of energy and concentration. It may not ever be learned and incorporated into their automatic behaviours; instead, it can be something that always requires extra devoted attention. To find what can be automated and what will always be only changed through masking requires asking the person with ASD about it, and some can’t communicate, so it can be very complex ground.

Asking ND kids to mask in order to make everyone else more comfortable because we like to be around “normal” people who do normal things, however, is asking them to use up their energy to assimilate. I think of it like this: Imagine someone who is physically able to walk only with concentration and difficulty, so they use a wheelchair to do all the things they need to do in a day. Then they’re prodded by teachers and peers to just walk more. They can walk across a room, but they won’t ever be able to walk without it taking a ton of energy. So, to accommodate people who are uncomfortable with differences, they might walk more often, but then they get exhausted by it and only get half as much done. People on the spectrum who are masking to fit in can get exhausted by all the masking and then can’t do all the things they might be able to do otherwise. For many, the disability doesn’t come from the diagnosis as much as it does from the lack of understanding in our environment.

We need much better education for NT people, with more recent and robust studies, to help them understand different ways people on the spectrum might perceive the world and to prevent inaccurate and harmful stereotypes about what we’re capable of.