I read a great deal of Bertrand Russell when I was in my teens. I read various collections of essays, such as Why I Am Not A Christian, In Praise of Idleness and Other Essays, and Marriage and Morals, some of which my father had stored in a box in the basement, along with Orwell’s 1984, Huxley’s Brave New World, a book or two by this guy named Freud, though I forget which one, and some others. I also Russell’s – dare I say it? – magisterial A History of Western Philosophy And Its Connection with Political and Social Circumstances from the Earliest Times to the Present Day, which I purchase myself, a big thick paperback with a white cover. It was cited when he received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950.

I read a great deal of Bertrand Russell when I was in my teens. I read various collections of essays, such as Why I Am Not A Christian, In Praise of Idleness and Other Essays, and Marriage and Morals, some of which my father had stored in a box in the basement, along with Orwell’s 1984, Huxley’s Brave New World, a book or two by this guy named Freud, though I forget which one, and some others. I also Russell’s – dare I say it? – magisterial A History of Western Philosophy And Its Connection with Political and Social Circumstances from the Earliest Times to the Present Day, which I purchase myself, a big thick paperback with a white cover. It was cited when he received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950.

It was from Russell more than anyone else that I got the idea that philosophy was a grand synthetic discipline, which I liked. Putting things together, seeing how all the parts interacted, that had immense appeal to me. And so I became a philosopher major when I enrolled in The Johns Hopkins University in 1965. I enjoyed an introductory course called, I believe, Types of Philosophy. Edward Lee’s course in Plato and the Pre-Socratics was wonderful as well; Lee was young, charismatic, and loved Mahler, as I did.

Then there was a two-semester sequence in the history of modern philosophy, from Descartes up through Kant. Maurice Mandelbaum taught the first semester, outlining each lecture on the board and then delivering on the outline. The lectures were so clear that you almost didn’t have to read the primary texts. The second semester was taught by a visitor from Chicago, Alan Gewirth. A different experience, like pulling teeth. Gewirth did the pulling and we students offered up our teeth. Ouch! But perhaps more pedagogically effective than Mandelbaum’s clarity, more Socratic, if you will.

By my junior year, however, I had come to realize that philosophy, as it is practiced in the academic world, is not what I had imagined it to be from reading Russell’s essay. It was another specialized discipline that had long ago abandoned any attempt at a broad synthesis. Fortunately, I had discovered literature, and Dr. Richard Macksey, whom I’ll discuss in more detail later. I’d always loved to read, and Macksey’s free-wheeling and broad ranging intellect appealed to me. I took four courses with him, plus an independent study on I forget what, and did a master’s thesis on “Kubla Khan” under his supervision. Literary criticism became the rubric under which I put things together. And why not? Literature expresses the world, and so couldn’t one study the world under the rubric of studying literature?

Well, no, if you must ask. By the time I’d figured that out – it didn’t take but a year or three – I was committed to an impossible intellectual project. I remain so committed. I will end this essay by arguing – it’s more of an earnest suggestion, really – that perhaps, if we do it right – of which there is no guarantee, and many signs that we’re botching it – we can harness these marvelous new machines to the job of synthesizing (human) knowledge. If we succeed, we’ll find ourselves in a whole new world, perhaps one where it is not at all obvious who is harnessed to what and to what end. I will, however, proceed indirectly.

Views about Machine Learning and Large Language Models

For example, consider the widely divergent views about AI and machine learning that have flooded the world’s town squares in the wake of OpenAI’s release of ChatGPT at the end of 2022. There have been a number of articles here, at 3 Quarks Daily. David Lobina is deeply skeptical; see his article What is Thought that a Large Language Model Ought to Exhibit (But Won’t)? In contrast, Oliver Waters is generally enthusiastic about the technology, an enthusiasm he expresses in Escape from Brain Prison, where he contemplates the possibility of installing the contents of our minds in computers. I believe that LLMs are amazing, but also very strange; we need to understand them.

The so-called Godfathers of AI are deeply divided. In a recent tweet Yann Lecun once more expressed his skepticism: “In 4 years, a child has seen 50 times more data than the biggest LLMs.” In an interview that he gave to the New York Times after he quit Google, Geoffrey Hinton expressed his current fears, fears he’d never had before:

“The idea that this stuff could actually get smarter than people — a few people believed that,” he said. “But most people thought it was way off. And I thought it was way off. I thought it was 30 to 50 years or even longer away. Obviously, I no longer think that.”

Cognitive scientist Gary Marcus continues to express his skepticism even as temporarily-ousted-not-so-long-ago OpenAI CEO Sam Altman is busy rounding up $7 trillion dollars – that’s 12 zeros, twelve! – apparently to keep the supply of computer chips flowing over the next couple of years as the systems get bigger and bigger and bigger and consume more and more and God-only-knows how much more electricity. More! More! More! Just how much unrequited testosterone is sloshing around in the streets in Silicon Valley?

That there is disagreement is not so much the issue as the fact that we don’t know what we’re disagreeing about. Sure, we can point to the machines, and the Chatbots, and talk about jobs, but when it comes to the core technology, how it works and what it can do, there is no conceptual framework we hold in common. There’s a good reason for that, of course: No one knows how it works. When you consider the complex web of skills and organizations needed to create this technology, it’s the most sophisticated “stuff” we’ve ever built, and it’s almost as mysterious as the human soul.

The fact is, Humpty Dumpty has fallen, the genie is out of the bottle, and we’re headed to hell in a Tesla in full self-driving mode. We have little choice but to deal with it. We’ll muddle through. But we’ll do so with perhaps a bit of grace if we can create a conceptual framework more adequate to the problems we have unleased upon ourselves.

That’s where philosophy comes in, but not the academic philosophy that bored me witless as an undergraduate. I have something else in mind. Think about a recent essay by Peter Godfrey-Smith, a philosopher of science with a particular interest in biology, “On the Relation Between Philosophy and Science” (which I found via Dan Dennett). Godfrey-Smith offers three roles: 1) intellectual integration, 2) conceptual incubation, and 3) critical-thinking skills. He regards the first as fundamental and as the most important of the three. I agree.

Here’s his basic statement of that role:

The best one-sentence account of what philosophy is up to was given by Wilfrid Sellars in 1963: philosophy is concerned with “how things in the broadest possible sense of the term hang together in the broadest possible sense of the term.” Philosophy aims at an overall picture of what the world is like and how we fit into it.

A lot of people say they like the Sellars formulation but do not really take it on board. It expresses a view of philosophy in which the field is not self-contained, and makes extensive contact with what goes on outside it. That contact is inevitable if we want to work out how the picture of our minds we get from first-person experience relates to the picture in scientific psychology, how the biological world relates to the physical sciences, how moral judgments relate to our factual knowledge. Philosophy can make contact with other fields without being swallowed up by them, though, and it makes this contact while keeping an eye on philosophy’s distinctive role, which I will call an integrative role.

There are, of course, many different accounts one might give of the relationship between first-person experience and scientific psychology and Godfrey-Smith plays no favorites in this paper; he doesn’t even discuss that particular issue. But he recognizes that first-person experience must be honored, and that’s an important recognition.

More recently Eric Schlisser has argued for synthetic philosophy (also, see this recent discussion at Crooked Timber, a rare “old-school” academic blog that is still productive):

By ‘synthetic philosophy’ I mean a style of philosophy that brings together insights, knowledge, and arguments from the special sciences with the aim to offer a coherent account of complex systems and connect these to a wider culture or other philosophical projects (or both). Synthetic philosophy may, in turn, generate new research in the special sciences, a new science connected to the framework adopted in the synthetic philosophy, or new projects in philosophy. So, one useful way to conceive of synthetic philosophy is to discern in it the construction of a scientific image that may influence the development of the special sciences, philosophy, public policy, or the manifest image. […]

Synthetic philosophy, which shares kinship with what was once known as ‘natural philosophy’ or (later) ‘philosophy of nature’ is made possible by, and a response to, the intellectual division of labor within and among the scientific disciplines. It requires skills that are orthogonal to the increasing specialization within the increasingly esoteric sciences. It is, thus, a modern phenomenon of the last two centuries.

I have, for some time now, believed that intellectual specialists have taken to writing broad-ranging books for the general public, which includes other intellectual specialists, out of a desire to pursue such synthetic thinking. I suspect that Steven Pinker wrote The Language Instinct mostly out of a desire to present linguistics to the general educated public. How the Mind Works is such a book as well. But it is also a book in which Pinker surveyed a broad range of material out of his own need for a more integrated account of the human mind. Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel is such a book, as is Stephen Mithen’s The Singing Neanderthals: The Origins of Music, Language, Mind and Body, and Daniel Dennett’s more recent, From Bacteria, to Bach, and Back: The Evolution of Minds.

My own book on music, Beethoven’s Anvil: Music in Mind and Culture, is in this vein. I ground the whole construction in the physics of coupled oscillation, firefly synchrony, and the complex neurodynamics of the late Walter Freeman. From there I move through the psychology and neuroscience of pleasure, emotion, rhythm and navigation; speculate on the role of music in catalyzing the origins of proto-humans from clever-apes; take a tour through altered states of (musical) consciousness; follow the elaboration of musical forms in the evolution of civilizations; consider the cultural-cross fertilization of musical cultures in the United States; and end with a lament that, with the advent of recording and broadcast technology, too few people spend much time in active music-making. Is it a seamless conceptual construction? No, how could it be? But it is all there, in one place, for you to examine it, think about, criticize it, and suggest improvements. That’s how we move from speculation to knowledge.

Before returning to philosophy, however, I want to look at a stage just prior to philosophy: Just how much information and knowledge can one person assimilate and deploy, but without necessarily attempting to integrate over it?

Tyler Cowen, Virtuoso Infovore

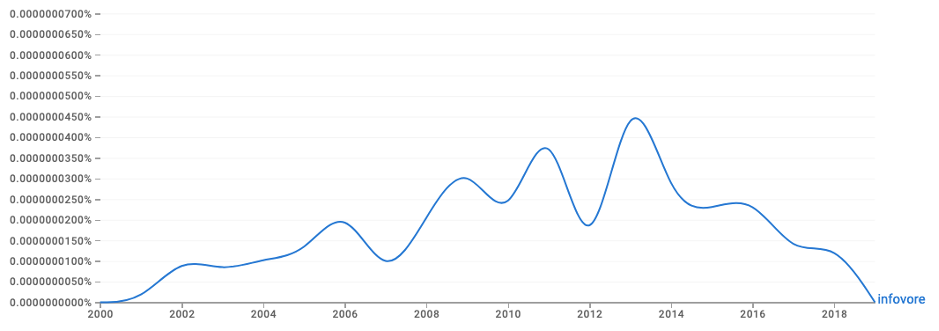

The term “infovore” was coined by a pair of neuroscientists, Irving Biederman and Edward Vessel, early in the new millennium. I have no idea how to account for the waning usage of the word after 2013 that is reflected in this Ngram chart. Noise or signal? I don’t know.

It means “person who indulges in and desires information gathering and interpretation.” By that definition I’m an infovore and many others are as well. I first heard the term through the economist and self-styled infovore, Tyler Cowen, who published The Age of the Infovore: Succeeding in the Information Economy back in 2010.

Before Cowen, and long before the word was coined, there was Dick Macksey, who certainly was a virtuoso infovore. A legendary figure at Johns Hopkins over the last half-century, he was my undergraduate teacher and mentor. He is perhaps best-known as one of the organizers of the 1966 structuralism conference that brought a gaggle of French intellectuals and provocateurs (including Derrida, Lacan, and Barthes) to America to battle it out among themselves while the locals, the few who could get in, looked on in disbelief. Macksey was also long-term editor of the comparative literature issue of MLN (Modern Language Notes), the second oldest literary journal in the United States, and, as such, a important intellectual gateway.

I remember him as a charismatic pipe-smoking professor who always wore a tie and jacket and frequently wore sunglasses, even indoors. He was trained in comparative literature and spoke I don’t know how many languages, perhaps a dozen. Apparently he learned Swedish so he could watch Bergman films without the subtitles. He knew the history of film backwards and forwards, as the saying goes, and at least two of his students went on to distinguished careers in Hollywood – Walter Murch (three Oscars) and Caleb Deschanel (six Oscar nominations and father of two daughters who are better known than he is, Emily and Zooey). He taught three and four courses a semester, when the normal teaching load was two. Later, that is, after I left Hopkins in 1972, he taught at the Medical School as well. His library, which eventually grew to 70K volumes (and seemed to be part of the support infrastructure of his house), was legendary, and was a minor internet meme for a bit. The first time I visited his house I saw a first edition of Russel and Whiteheads Principia Mathematica stacked on a chair in the entrance way and a copy of Gell-Mann and Ne’eman, The Eightfold Way (about physics, not Buddhism), on a coffee table in the living room. There may have been a copy of The Doors stacked near the stereo.

He seems to have memorized chunks of every book he’d read and would quote substantial passages in class (I’ve read that the late Harold Bloom had the same ability). I often thought that, if you picked any two topics, Macksey could create a bridge between the two in no more than five conceptual jumps. Quantum entanglement to Paul Bocuse, Ernest Shackleton to The Tale of Genji, Pareto efficiency to C. Elegans – leaps like that. I never tested it out, but it just seemed like the way Macksey’s mind worked.

As for Tyler Cowen, he’s an infovore of a different stripe. Trained in economics, along with his colleague Alex Tabarrok, he’s run the Marginal Revolution blog for over two decades, posting in it every day. Almost every day there’s a link post, giving links to a half-dozen or more things he finds interesting. Here are the links from Friday, February 23:

- Is dancing the best treatment for depression? Limited data, speculative.

- Tom Cruise will use new deal to do more “auteur” movies.

- Ginevra Lily Davis on women, good piece.

- A look inside a nuclear submarine.

- The project of trying to make yourself more agentic.

- Niklaus Wirth, RIP (NYT).

- Will there be a hydrogen energy gold rush? (FT)

I check the blog every day, and comment a couple of times a week. If only two or three of those links pan out for me in a week, it’s worth the time. If you go to my home blog, New Savanna, you’ll find 25 posts (going back to 2018) that I’ve tagged with Tyler Cowen, but considerably more mention him. Those run back to 2010, the year I started the blog; most of them simply acknowledge that I found something at Marginal Revolution.

There’s more to Marginal Revolution than link-lists. Cowen generally posts sentences and paragraphs from things he’s read, but also his columns for Bloomberg. Every few weeks he’ll post single-sentence lists of books he’s been reading in a wide variety of topics from soup to the history of economics, music he’s been listening to (he’s a fan of Bach and the Beatles), and movies he’s seen. And then we have the excerpts from his podcasts, Conversations with Tyler. Recent interviews include: Masaaki Suzuki, conductor, Amy Vitale, photojournalist, Fuchsia Dunlop, expert on Chinese cuisine (Cowen’s a foodie), John Gray, Philosopher, Githae Githinji, a Kikuyu elder, Paul Graham, entrepreneur, and so forth and so on for a list that’s currently at 204.

Next up, Emergent Ventures, a philanthropic program he runs. The web page reads:

Launched in 2018, Emergent Ventures is a low-overhead fellowship and grant program that supports entrepreneurs and brilliant minds with highly scalable, “zero to one” ideas for meaningfully improving society. Mercatus Center faculty director Tyler Cowen administers the program. Grants are awarded to thinkers and doers around the world, with dedicated support available for projects with a focus on India, Africa and the Caribbean, or Ukraine. Applicants with a specific geographic focus should select the appropriate region from a drop-down menu on the application form.

The application form is simple and you get a decision in weeks. Some grants go to high school students and some go to seasoned veterans. Though I don’t actually know the amounts, judging from the projects, which he lists periodically on Marginal Revolution, I’d imagine they range from 1000s to perhaps low six figure dollar amounts in a few cases.

There’s more, but that’s enough to give you a sense of the man.

I want to use one of Cowen’s most recent projects to shift gears, his recent (self-published) book, GOAT: Who is the Greatest Economist of all Time, and Why Does it Matter? The COVID pandemic put a damper on his usual activities – he likes to travel and has been to over 100 countries – and left him with a lot of time to fill. He decided to fill it with one of his intellectual passions, the history of economics. He wrote the book as fan, his word, for a general audience. He doesn’t end up naming the one and only GOAT economist, but offers a selection of six: Milton Friedman, Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, John Maynard Keynes, Friedrich A. Hayek, and Thomas Robert Malthus.

“But,” you might object, “Mill wasn’t an economist. He was a philosopher, no?” Yes, he was a philosopher, but he was also an economist. In Cowen’s terms, “The deepest and most comprehensive thinker of all economists.” In Mills’ time philosophy hadn’t become the specialized academic discipline it subsequently became, and still is. It was the broad integrative intellectual that Peter Godfrey-Smith talks about.

Consider this passage from the end of Cowen’s book (p. 348):

Today’s economists are smarter and better trained than ever before, but something about economics has changed fundamentally. More specifically, economics is no longer a carrier of ideas. It is primarily a means of data collection and very sophisticated hypothesis testing. If you look at the works of the economists discussed in this book, they were all deeply concerned with questions of broader social evaluation. They all had ideas that went beyond economics into economic and political philosophy. And they are all plausible contenders for GOAT.

The book concludes with a lament (349):

I don’t think the hypothesis testers, whatever their virtues, ever will contend for GOAT. They will win other titles, such as “tenured professor at Ivy League school” and “Nobel laureate,” and they will deserve them. But GOAT will remain something special, and even striving for GOAT will be reserved for those who see the world in the biggest, broadest possible terms.

But those individuals are no longer the top economists, and they will not resume that mantle anytime soon, probably never.

There is one more thing about the book that you need to know. When Cowen posted the book to the web, he also provided links to chatbots trained on the book, allowing you to query it through GPT-4 and Claude.

There is a deeper lesson here. Cowen has conducted his intellectual life in a way that would have been impossible before the invention of the internet. Furthermore, while he has a secure academic post at George Mason University, and has published in the formal academic literature, he has stated that he’s striven to become an influential economist by working outside the institutions of the academy. Writing a chatbot-enabled general audience book about great economists is but another step outside existing academic institutions.

As Kurt Vonnegut kept repeating in Slaughterhouse Five, “So it goes.”

So it goes.

Artificial Intelligence as a catalyst for intellectual integration

OK, so the technology’s cool. Just how does that help with the problem of philosophical integration when the technology itself cries out for it? There, that’s it, that’s a place to start. As I argued at some length not so long ago, the people who are expert in the technology itself, tend to be uninformed and naïve about psychology, cognitive science, linguistics and yet they are speculating and making pronouncements about when the technology will be able to perform as well or even better than humans on this or that task, maybe even all of them.

Beyond that, think about what is actually in those large language models (LLMs): a big chunk of human knowledge. Consider the “Macksey game” that I’ve already mentioned, making connections between arbitrarily chosen bits of knowledge. I’d never put Macksey himself to the test, but I’ve done so with ChatGPT. I gave him the following three trials: Quantum entanglement to Paul Bocuse, Ernest Shackleton to The Tale of Genji, Pareto efficiency to C. Elegans. It came up with conceptual paths in all cases, not necessarily in five links – but then I didn’t explicitly ask for that – but it did make connections, which you can examine in the appendix at the end of this article.

That ChatGPT could do that is not at all surprising. How could it not? It’s got the necessary information in the model, and that information has to be highly organized in order to enable ChatGPT produce all that fluent, if bland, prose. If we can figure out how that information is organized – now we’re going somewhere. We’re going “meta” on the structure of human knowledge embedded in the underlying LLM.

That’s what I had in mind when I published World, Mind, Learnability, Large Language Models, and the Metaphysical Structure of the Cosmos last April here in 3QD. As Ted Underwood, an expert in cultural analytics, argued in 2021, LLMs are Mapping the latent spaces of culture. They are ontological machines.

Here I am using “ontology” in the sense that it has come to have in computer and information science, rather than in the sense it has for philosophers. Philosophers are concerned about what exists; informaticians are interested in how we conceptualize the world. In the somewhat technical language of John Sowa:

The subject of ontology is the study of the categories of things that exist or may exist in some domain. The product of such a study, called an ontology, is a catalog of the types of things that are assumed to exist in a domain of interest D from the perspective of a person who uses a language L for the purpose of talking about D.

Notice that Sowa specified that ontologies exist with respect to specific domains.

Conceptually, though not physically, salt and sodium chloride are not the same thing. As I pointed out in an article published in the Handbook of Metaphysics and Ontology back in 1991, Ontology of Common Sense, “salt” is a common-sense concept defined in by its color, shape and texture and, above all, by its taste. “Sodium chloride” is an abstract concept defined in terms of atoms of elements and bonds between them. That ontology didn’t exist until the 19th century. When I was on the faculty at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute I consulted with the Center for Integrated Manufacturing where I produced a technical report in which I sketched out the core of an ontology the world of mechanisms: Ontology in Knowledge Representation for CIM. When Thomas Kuhn talks of revolutionary science involving a paradigm change, he is in effect saying that there’s a change in conceptual ontology. When Michel Foucault writes of different historical epistemes, he’s writing about different conceptual ontologies and the power structures they’re embedded in.

Returning to LLMs, I know from my experimentation with ChatGPT that it is sensitive to ontological distinctions. One task I’ve given it goes like this: I give it a short story set in a fairy tale universe. I then ask it to create a new story based on that one by changing the protagonist in a way that I specify. The protagonist is Princess Aurora. When I ask that the new protagonist be Prince Harry, the new story differs from the original in minor and relatively predictable ways. When I ask it make Aurora a creature designated XP-708-DQ the whole story changes. XP-708-DQ turns out to be a robot in the new story, though I didn’t ask for that, and the story takes place in a science fiction universe, a universe with a different underlying ontology.

Then I gave it this prompt: “am going to tell you a story about princess Aurora. I want you to tell the same story, but change princess Aurora to a colorless green idea. Make any other changes you wish.” Its response:

I’m sorry, but the concept of a “colorless green idea” is a nonsensical phrase that was invented as an example of a phrase that would be grammatically correct but semantically meaningless. It is not possible to create a story about a “colorless green idea” as it does not have any physical properties or characteristics that can be used in a story.

That is to say, it rejected the prompt on ontological grounds. “Colorless green idea” was not the kind of thing needed to do the job requested of it.

In a different experiment I issued a series of prompts resulting a fairy tale story about how Lily, along with and her friends and relatives, engages in a successful rebellion against the king. Then I asked it: “What happened in this new order when a flying saucer landed outside the village and a robot named Gort got out?” By now you should be able to guess how ChatGPT responded. It refused to honor the prompt, but was polite about it:

It sounds like you might be referring to a classic science fiction film called “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” which features a robot named Gort and a flying saucer landing on Earth. However, as Lily’s story has not previously included elements of science fiction or extraterrestrial visitors, I’m afraid I cannot answer this question within the context of her story. If you have any other questions about Lily and her world, I would be happy to try and answer them for you!

In a more pedestrian vein, I’ve had ChatGPT play the game of 20 questions, aka “animal, vegetable, or mineral.” That game requires it to track its way through ontological structure to identify the concept I’ve got in mind. In 12 trials, six with abstract concepts (justice, evolution, and truth, twice each) and six with concrete concepts (bicycle, squid, and apple, twice each), ChatGPT performed better at guessing the abstract concepts. I don’t know why.

I am thus sure that ChatGPT, that is to say, the LLM underlying and driving the chatbot, is sensitive to matters of conceptual ontology. But it is one thing to present ChatGPT with tasks that reveal its sensitivity to ontological structure. That is, however, a long way from actually knowing what that intellectual structure is. For that we’re going to have to take a look inside.

There are people doing that, not enough of them, but some. It’s one thing to take a look. Making sense of what you find among those billions and billions of parameters, that’s another matter. In a recent podcast, Ellie Pavlick, a cognitive scientist who runs the Language Understanding and Representation Lab at Brown University, has said that within “the five to ten year time frame [we] will be able to say something precise and meaningful about how they work” (15:35). Given what I’ve read from various sources, the implications of my own work, and conversations I’ve been having with Ramesh Visvanathan, who leads the Center for Cognition and Computation at Goethe University Frankfurt, I think that’s a reasonable time frame.

Any success we have in that problem will necessarily constitute progress toward the philosophical problem I outlined earlier, the reconciliation of people’s first-person experience of the technology, Chatbots certainly, but also the whole range of technologies bubbling up through the major research labs to the web, with a scientific and engineering account of how they work. Such a philosophical framework will benefit everyone, the people who create and maintain the technology, those who use it directly (before long, most/all of us), and those must make policies governing its development and deployment. The fact that such a philosophical integration is possible, alas, does not imply that is will in fact be undertaken, much less accomplished.

All Together Now

As I see it, that will be a massive undertaking. As I said in said in December of 2022 about so-called Foundation Models:

I have come to think of each such models as repositories of digital wilderness.

What do we do with the wilderness? We explore it, map it, in time settle it and develop it. We cultivate and domesticate it. AI safety researchers call that alignment. The millions of people who have been using ChatGPT are part of that process. We may not think of ourselves in that way, but that, in part, is how OpenAI thinks of us. Even as we pursue our own ends while interacting with ChatGPT, OpenAI is collecting those sessions and will be using them to fine-tune the system, to align it.

I can’t help but think that that will be a highly distributed, multi-year, multi-decade, and perhaps even a multi-generational process. I see little reason to believe that current institutions will undertake the task willingly. Change is difficult enough for individuals, deep change, ontological change. It is much worse for institutions, for the coordination problems are enormous – that’s what cultural evolution is about. Current institutions, private and public, for-profit and non-for-profit, are weighed down by their entanglement in present arrangements, which extend back into the 19th century.Fortunately we’re not all tightly bound to those institutional structures. There are lots of nooks and crannies in large flourishing democracies, even ones as sorely tried as America currently is, for rambunctious and adventuresome mammals to scurry about hidden away from the grappling dinosaurs. Anyone with a laptop and an internet connection can undertake the kinds of investigations I have done, and many others as well. The basic ideas and principles of conceptual ontology are readily explained to any intelligent teenager and the ideas are readily available on the web.

This revolution will not be televised. That technology is all but obsolete. With any luck the revolution may not even be noticed until it is too late. Perhaps, just perhaps…help is on the way.

Appendix: ChatGPT plays the Macksey Game

Here’s how I played the Macksey game with ChatGPT. I gave it an example in my prompt and then asked it to make connections in separate prompts.

If someone asked me to make conceptual connections between, say, Queen Elizabeth and the Voyager spacecraft, I might do it like this:

- Elizabeth was Queen of England, the home of Isaac Newton.

- Newton was a physicist who formulated 3 laws of motion and the law of gravitation.

- The laws of motion are important in understanding how rockets work.

- The law of gravitation tells us how to track the motions of the planets and bodies moving through the solar system.

- NASA used both the laws of motion and the law of gravitation in the Voyager mission.

I want you to do the same thing with, say, Quantum entanglement and Paul Bocuse. Construct a string of connections between them.

Certainly! Let’s create conceptual connections between Quantum entanglement and Paul Bocuse:

- Quantum Entanglement is a phenomenon in quantum physics where two or more particles become connected and correlated in such a way that the state of one particle directly influences the state of the other, regardless of the distance between them.

- The study of quantum mechanics and phenomena like entanglement involves understanding the fundamental principles that govern the behavior of particles at the quantum level.

- Quantum mechanics has applications in various fields, including chemistry. The molecular structures and interactions in cooking, particularly in the creation of complex flavors and textures, are governed by principles rooted in quantum mechanics.

- Paul Bocuse, a renowned French chef, was a pioneer in the culinary world known for his innovative approach to cooking and emphasis on the quality of ingredients.

- In cooking, the flavors and textures of different ingredients can be intricately linked, much like entangled particles in quantum mechanics. Bocuse’s culinary creations often involved the careful balance and interplay of various elements to create a harmonious and delightful dining experience.

- Just as quantum entanglement involves the entwining of particles, Bocuse’s approach to cuisine entwined diverse flavors and textures to elevate the overall culinary experience.

In this way, we can draw conceptual connections between Quantum entanglement and Paul Bocuse by exploring the underlying principles of quantum mechanics and how they manifest in the artistry of culinary creations.

How about Ernest Shackleton to The Tale of Genji.

Certainly! Let’s create conceptual connections between Ernest Shackleton and “The Tale of Genji”:

- Ernest Shackleton was a renowned Anglo-Irish explorer best known for leading the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition.

- During Shackleton’s expeditions, he faced extreme conditions in Antarctica, navigating icy waters and challenging terrains.

- “The Tale of Genji” is a classic Japanese work of literature written by Murasaki Shikibu in the early 11th century, often considered one of the world’s first novels.

- Genji, the protagonist of the tale, is a nobleman who faces various challenges and adventures in the imperial court of Heian Japan.

- While Shackleton’s expeditions focused on the harsh conditions of the Antarctic, “The Tale of Genji” explores the intricate social and emotional landscapes of the Heian court.

- Both Shackleton’s Antarctic expeditions and “The Tale of Genji” involve tales of human resilience and the ability to navigate through challenging environments, whether physical or social.

- Shackleton’s leadership qualities, especially his ability to keep his crew motivated in the face of adversity, can be compared to the complex interpersonal relationships depicted in “The Tale of Genji.”

- Both narratives touch upon themes of isolation, survival, and the human spirit’s capacity to endure and overcome challenges.

By weaving these connections, we can draw parallels between Ernest Shackleton’s Antarctic explorations and the timeless narrative of “The Tale of Genji,” exploring themes of resilience, leadership, and the human experience in diverse environments.

One more: Pareto efficiency to C. Elegans.

Certainly! Let’s create conceptual connections between Pareto efficiency and C. elegans:

- Pareto efficiency is an economic concept that describes a situation where it is impossible to make any party better off without making another party worse off. It represents an optimal allocation of resources where no one can be made better off without making someone else worse off.

- In the world of economics, Pareto efficiency is often associated with the idea of maximizing overall welfare or utility.

- elegans is a microscopic nematode worm widely used in biological research due to its simplicity and well-mapped nervous system.

- The study of C. elegans has contributed significantly to understanding fundamental biological processes, including genetics and neurobiology.

- In the context of Pareto efficiency, one can draw a parallel with the efficiency of biological systems. C. elegans, as a model organism, represents an efficient biological system that has evolved to optimize survival and reproduction in its environment.

- The genetic and neural simplicity of C. elegans allows researchers to study fundamental principles of biology in an efficient and effective manner.

- Just as Pareto efficiency seeks an optimal allocation of resources, the genetic and neural makeup of C. elegans can be considered an optimal allocation of biological components for its survival and reproduction.

- Both concepts, Pareto efficiency in economics and the biological efficiency of C. elegans, involve the idea of optimization and achieving the best possible outcomes within given constraints.

By connecting these concepts, we can explore the notions of efficiency in different domains, drawing parallels between the economic concept of Pareto efficiency and the biological efficiency observed in the model organism C. elegans.