by Steve Szilagyi

An air of the erotic hangs over “Norman Rockwell: The Scouting Collection” – a show of 65 paintings by America’s master illustrator currently on display at the Medici Museum of Art in Warren, Ohio.

The pictures came to the Medici Museum after a Los Angeles Times article revealed that the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) had covered up decades of child sexual abuse by scout leaders and volunteers – triggering epic lawsuits and eventually sending the BSA into bankruptcy.

The Medici Museum is a stark-white building in the middle of a large, empty parking lot. Pushing through its glass doors, the first thing you see on the wall is an icon of American illustration: Norman Rockwell’s 1959 painting of a cheerful scout, captured mid-stride, waving to the viewer. This was the cover of that year’s Boy Scout Handbook. The next thing you see is a naked woman, kneeling to the right of Rockwell’s scout – and you immediately go over to check her out. She looks so real!

The nude is one of several figures by American artist Carole Feuerman owned by the Medici. Feuerman is a former illustrator who switched to erotic sculpture in 1978 and now specializes in hyper-realistic swimmers. The Medici displays Feuerman’s figures cheek by jowl with Rockwell’s scouts in one of the odder juxtapositions you’ll ever see in a small, regional museum – places where odd juxtapositions are often the rule.

As we all know, Norman Rockwell is the preeminent illustrator of the 20th century. His paintings, once scorned by connoisseurs, are now eagerly sought after by the likes of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. Top-tier Rockwells have gone for up to $48 million at auction. Although the collection of paintings at the Medici includes some third and fourth-rate Rockwells, it’s still said to be valued at around $120 million.

How did these valuable pictures wind up in a modestly sized museum, in a suburb of a small city, just outside Youngstown, Ohio? A museum that was only established in its present form in 2020? Read more »

Arguably the greatest global health policy failure has been the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) refusal to promulgate any regulations to first mitigate and then eliminate the healthcare industry’s significant carbon footprint.

Arguably the greatest global health policy failure has been the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) refusal to promulgate any regulations to first mitigate and then eliminate the healthcare industry’s significant carbon footprint.

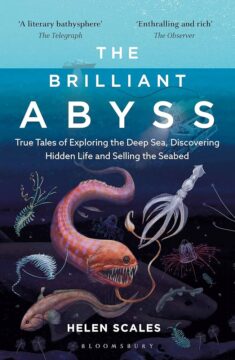

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ previous book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, brilliantly provided us with a glimpse of the wondrous life forms that inhabit the abyss, the deep sea. She also made known her profound concern for the future of ocean life posed by human activity. She now expands on those issues and concerns in her new book, What The Wild Seas Can Be: The Future of the World’s Seas. Scales provides us with a fascinating exposition of the pre-historic ocean and the devastating impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life over the last fifty years. Her main concern, however, is the future of the ocean and her new book makes a major contribution to people’s understanding of the repercussions of human activity on ocean life and the measures that need to be taken to protect and secure a better future for the ocean.

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ previous book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, brilliantly provided us with a glimpse of the wondrous life forms that inhabit the abyss, the deep sea. She also made known her profound concern for the future of ocean life posed by human activity. She now expands on those issues and concerns in her new book, What The Wild Seas Can Be: The Future of the World’s Seas. Scales provides us with a fascinating exposition of the pre-historic ocean and the devastating impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life over the last fifty years. Her main concern, however, is the future of the ocean and her new book makes a major contribution to people’s understanding of the repercussions of human activity on ocean life and the measures that need to be taken to protect and secure a better future for the ocean.

In this conversation—excerpted from the Aga Khan Award for Architecture’s upcoming volume, Beyond Ruins: Reimagining Modernism (ArchiTangle, 2024) set to be published this Fall, and focusing on the renovation of the Niemeyer Guest House by East Architecture Studio in Tripoli, Lebanon—

In this conversation—excerpted from the Aga Khan Award for Architecture’s upcoming volume, Beyond Ruins: Reimagining Modernism (ArchiTangle, 2024) set to be published this Fall, and focusing on the renovation of the Niemeyer Guest House by East Architecture Studio in Tripoli, Lebanon—

Michael Wang. Holoflora, 2024

Michael Wang. Holoflora, 2024 In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

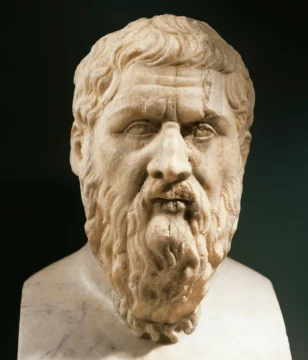

In Discourse on the Method, philosopher René Descartes reflects on the nature of mind. He identifies what he takes to be a unique feature of human beings— in each case, the presence of a rational soul in union with a material body. In particular, he points to the human ability to think—a characteristic that sets the species apart from mere “automata, or moving machines fabricated by human industry.” Machines, he argues, can execute tasks with precision, but their motions do not come about as a result of intellect. Nearly four-hundred years before the rise of large language computational models, Descartes raised the question of how we should think of the distinction between human thought and behavior performed by machines. This is a question that continues to perplex people today, and as a species we rarely employ consistent standards when thinking about it.

In Discourse on the Method, philosopher René Descartes reflects on the nature of mind. He identifies what he takes to be a unique feature of human beings— in each case, the presence of a rational soul in union with a material body. In particular, he points to the human ability to think—a characteristic that sets the species apart from mere “automata, or moving machines fabricated by human industry.” Machines, he argues, can execute tasks with precision, but their motions do not come about as a result of intellect. Nearly four-hundred years before the rise of large language computational models, Descartes raised the question of how we should think of the distinction between human thought and behavior performed by machines. This is a question that continues to perplex people today, and as a species we rarely employ consistent standards when thinking about it. The human tendency to anthropomorphize AI may seem innocuous, but it has serious consequences for users and for society more generally. Many people are responding to the

The human tendency to anthropomorphize AI may seem innocuous, but it has serious consequences for users and for society more generally. Many people are responding to the

I’ve been surfing for about three years.

I’ve been surfing for about three years.  Sughra Raza. After The Rain. Vermont, July 2024.

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. Vermont, July 2024.