by Mike Bendzela

I begin writing this essay the morning after dumping into the woods the sixth porcupine I have had to kill this growing season. It used to be that I would not see any evidence of porcupine damage in my apple trees until early August, but this year I began seeing chewed-off branches in late June. As with other ecological aberrations, it’s tempting to attribute the early arrival of porcupines in the orchard to a warming planet: We experienced a preternaturally early heatwave in mid-June in Maine, breaching 90 degrees on the 19th. Then it shot up to 96 degrees on the 20th, which is just weird. It stayed so hot through July that my onions and potatoes stopped growing and my broccoli failed to head up. All apple varieties are at least a week ahead of schedule this year. In the midst of this, I had to start my weekly scouting ritual extra early, going out into the orchard after midnight with a .22 pistol to deal with spiny rodents in the trees.

Why even shoot porcupines out of trees? It is undoubtedly a despicable practice, and I hate guns, but I can find no way around it. Porcupines love apple trees, and if left to themselves they will chew bark, branches and fruit until the trees are denuded of apples and permanently damaged. Then the well-fed porcupines will produce porcupettes, who will return to the orchard next season to continue the damage.

“Damage” is a matter of perspective. The porcupines are just doing what porcupines do — eat trees. They are rodents, with long, curving claws and incisors that continue to grow throughout their lives. The teeth are orange because they are literally iron-fortified. The animals can gnaw branches right off the trees and then descend to the ground to take bites out of apples. Sometimes they stay in the tree and go from apple-to-apple, gnawing and chewing. The damage they do is often shocking, but they are only doing to the trees what we humans do to lobsters — tear them to shreds and eat them. Read more »

Chakaia Booker. Romantic Repulsive, 2019.

Chakaia Booker. Romantic Repulsive, 2019. I will use this column to defend myself against the accusation, first made by my surgical assistant Mr. Alan Turing, that I was negligent in the death of an individual under my medical care. Or, as one armchair prosecutor has said, that I am “a stereotypically British sentimentalist who thinks dogs are more human than people.”

I will use this column to defend myself against the accusation, first made by my surgical assistant Mr. Alan Turing, that I was negligent in the death of an individual under my medical care. Or, as one armchair prosecutor has said, that I am “a stereotypically British sentimentalist who thinks dogs are more human than people.”  There is a beautiful garden in a quiet tree-lined street in Manhattan’s Little Italy. There are rows of flower, lush, abundant and slightly wild, a stone balcony you can imagine Romeo climbing up to, stone balustrades, several lions, one with climbing vines adorning his face, a sphynx, various other statues, a copy of a Hermes medallion from the late antiquity, a fig tree and a hydrangea tree, giant shady pear trees, and many small hidden paths that lead to gazebos and intimate garden spaces. People in the garden sit and while the time or read by a little table. In a very small space, Elizabeth Street Garden has been able to replicate the richness of life, spaciousness of spirit, the magnanimity and dedication to beauty of the best Italian gardens. It is one of the truly great places in NYC. But after 12 years of struggle between the city and garden advocates, on June 18, 2024, the

There is a beautiful garden in a quiet tree-lined street in Manhattan’s Little Italy. There are rows of flower, lush, abundant and slightly wild, a stone balcony you can imagine Romeo climbing up to, stone balustrades, several lions, one with climbing vines adorning his face, a sphynx, various other statues, a copy of a Hermes medallion from the late antiquity, a fig tree and a hydrangea tree, giant shady pear trees, and many small hidden paths that lead to gazebos and intimate garden spaces. People in the garden sit and while the time or read by a little table. In a very small space, Elizabeth Street Garden has been able to replicate the richness of life, spaciousness of spirit, the magnanimity and dedication to beauty of the best Italian gardens. It is one of the truly great places in NYC. But after 12 years of struggle between the city and garden advocates, on June 18, 2024, the

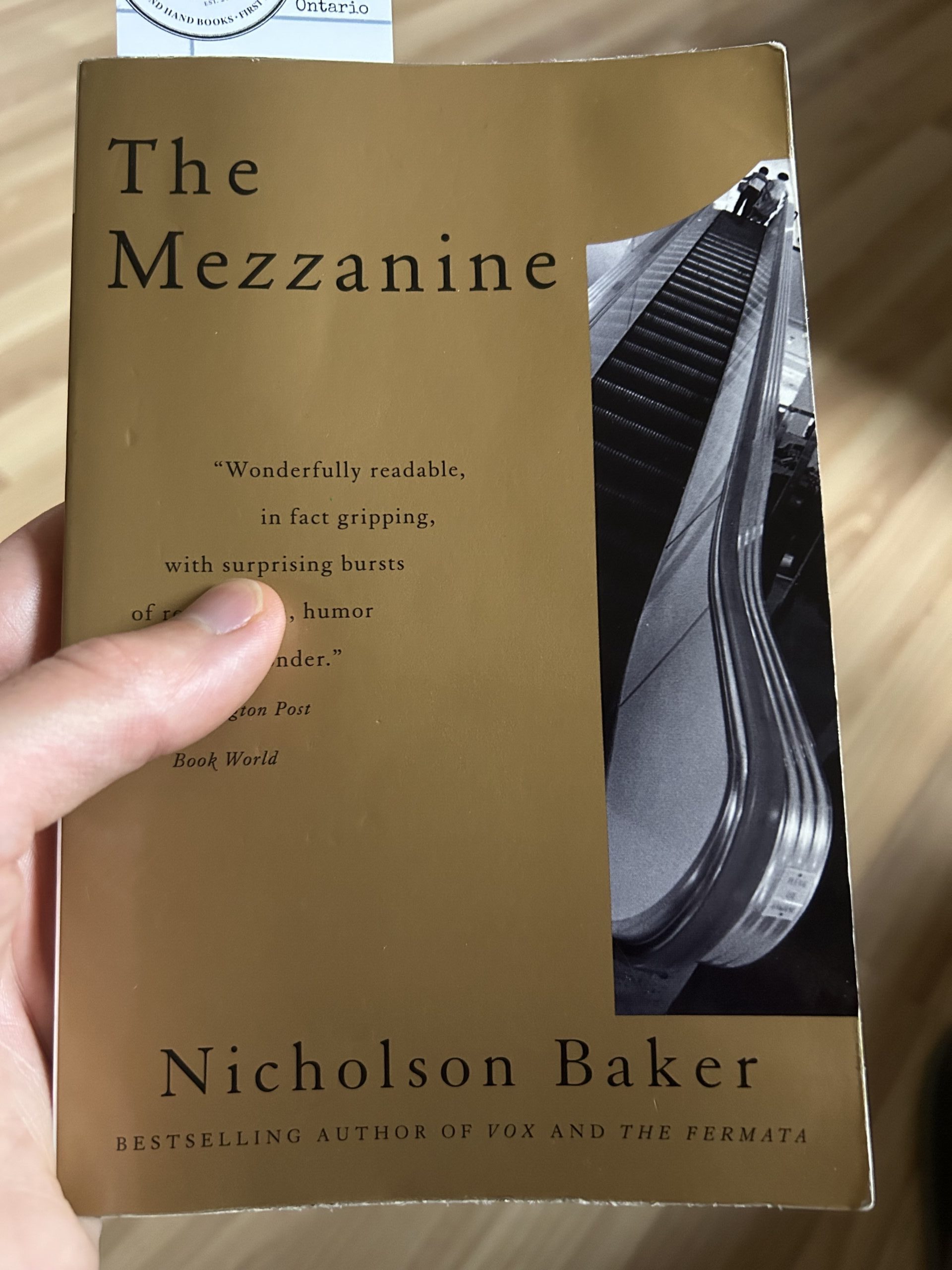

e Mezzanine by Nicholson Baker is a novel about paying attention. After you read a chapter, you, too, begin paying attention to things you’ve never noticed before.

e Mezzanine by Nicholson Baker is a novel about paying attention. After you read a chapter, you, too, begin paying attention to things you’ve never noticed before.

Robert McDonnell was the Governor of Virginia in 2014 when the federal government indicted him and his wife on bribery charges. A Virginia businessman named Jonnie Williams provided the McDonnells with over $175,000 in “loans, gifts and other benefits.” In exchange, the Governor “arranged meetings, hosted events, and contacted other government officials” in an effort to advance the fortunes of Anatabloc, a nutritional supplement manufactured by Williams’ company.

Robert McDonnell was the Governor of Virginia in 2014 when the federal government indicted him and his wife on bribery charges. A Virginia businessman named Jonnie Williams provided the McDonnells with over $175,000 in “loans, gifts and other benefits.” In exchange, the Governor “arranged meetings, hosted events, and contacted other government officials” in an effort to advance the fortunes of Anatabloc, a nutritional supplement manufactured by Williams’ company. Sughra Raza. Remains of The Day. Oolloo House, Vermont, August 2024.

Sughra Raza. Remains of The Day. Oolloo House, Vermont, August 2024.