by Laurence Peterson

I do not specifically remember when I lost my you-know-what about the way the word “humanitarian” is being tossed around these days. Possibly it was when a State Department spokesperson referred to what he called “humanitarian circumstances”, implying thereby that the designation could be sensibly applied to purely chance events. Or maybe the sheer obscenity of tagging the word to “zones” in middle of what is probably the most hellish place on earth right now (only to bomb the same areas anyway, subsequently) did the trick. Whatever it was, I have decided to try, for what it is worth, to come to terms with the matter. So here goes.

In my lifetime, which has spanned 63 years and some change now, I don’t recall the word being used that much except to describe individual persons and certain organizations, until rather recently. But, maybe starting in the ‘nineties, conditions began taking on the designation, especially in the media and in public relations; and phrases like the one I have chosen for my title, “humanitarian disaster”, or “humanitarian catastrophe” became more common. I distinctly remember at this time being annoyed by this: was the disaster supposed to be experienced primarily by the humanitarians? It kind of sounded to me like that was a real possibility. If that was not the case, why use the word humanitarian at all? Why not just call it a disaster or catastrophe? It seemed like something unseemly lay at the core of the reasoning that surrounded the employment of such phrases; like something rather sanctimonious was being smuggled in, too.

So I decided to try to understand what might be at the logical core of this kind of usage of words. What struck me at first was the employment of the word humanitarian was possibly being invested with a tacit, but palpable preeminence amongst possible adjectives in any specific case. Humanitarian concerns are somehow supposed to reflect a self-evident moral superiority over other ones, so that when the word is employed, there is a suggestion that the humanitarian concern should, perhaps prima facie, be considered the most important consideration. I am certain many people would, naively or otherwise, assent to this assertion (some environmentalists might consider environmental concerns to be paramount compared to humanitarian ones in certain cases, but, even here, many of them would consider both environmental and humanitarian matters to be of utmost importance). Read more »

In an age where there is little agreement about anything, there is one assertion almost everyone agrees with—there is no disputing taste. If someone likes simple food instead of complex concoctions, who is to say that’s wrong. If I prefer bodice rippers to 19th Century Russian novels, you might say my tastes are crude and uncultured but hesitate to say one type of literary work is inherently better than the other. Aesthetic judgments are about subjective preference only. This is especially true of food and drink. Our preferences in this domain seem especially subjective. You can’t be wrong if you dislike chocolate ice cream can you?

In an age where there is little agreement about anything, there is one assertion almost everyone agrees with—there is no disputing taste. If someone likes simple food instead of complex concoctions, who is to say that’s wrong. If I prefer bodice rippers to 19th Century Russian novels, you might say my tastes are crude and uncultured but hesitate to say one type of literary work is inherently better than the other. Aesthetic judgments are about subjective preference only. This is especially true of food and drink. Our preferences in this domain seem especially subjective. You can’t be wrong if you dislike chocolate ice cream can you?

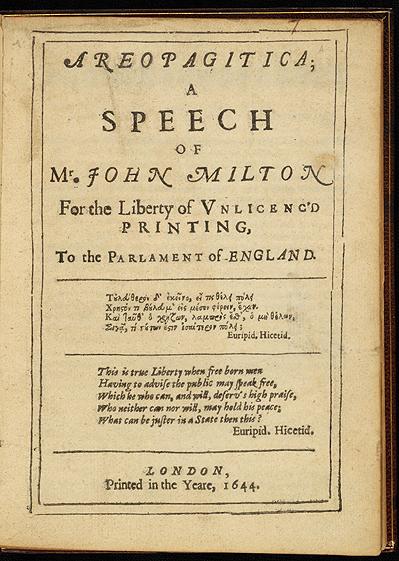

How do we regulate a revolutionary new technology with great potential for harm and good? A 380-year-old polemic provides guidance.

How do we regulate a revolutionary new technology with great potential for harm and good? A 380-year-old polemic provides guidance. Firelei Báez. Sans-Souci, (This threshold between a dematerialized and a historicized body), 2015.

Firelei Báez. Sans-Souci, (This threshold between a dematerialized and a historicized body), 2015.

I take the row covers off of two forty-foot rows of beans (three varieties) as the plants have become so big so fast in the ungodly heat they are pressing against the cloth. Afterwards, in the early evening, I let the chickens out of their sweltering little house to run free for a couple of hours. I will watch them to see if they bother the plants. The birds might peck at and scratch up the bean plants, but these plants are so large the birds should be indifferent to them. The experiment is a success: The plants bask in full sunlight while the birds rummage for grubs around them. I decide to leave the row covers off for now and will recover them at night to deter the deer. One’s smallness is manifested in gardening, as the gardener is a single organism set against myriads. It is wise to tend to one’s insignificance during these times. Come what may, no one will care much about those who stay at home husbanding rows of Maxibel haricots.

I take the row covers off of two forty-foot rows of beans (three varieties) as the plants have become so big so fast in the ungodly heat they are pressing against the cloth. Afterwards, in the early evening, I let the chickens out of their sweltering little house to run free for a couple of hours. I will watch them to see if they bother the plants. The birds might peck at and scratch up the bean plants, but these plants are so large the birds should be indifferent to them. The experiment is a success: The plants bask in full sunlight while the birds rummage for grubs around them. I decide to leave the row covers off for now and will recover them at night to deter the deer. One’s smallness is manifested in gardening, as the gardener is a single organism set against myriads. It is wise to tend to one’s insignificance during these times. Come what may, no one will care much about those who stay at home husbanding rows of Maxibel haricots.

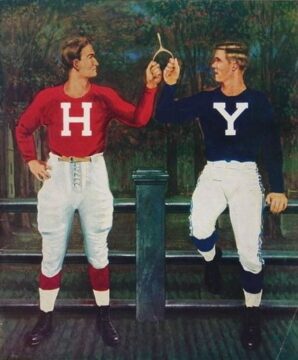

This week marks one year since Affirmative Action was repealed by the Supreme Court. The landmark ruling was a watershed moment in how we think of race and social mobility in the United States. But for high schoolers, the crux of the case lies somewhere else entirely.

This week marks one year since Affirmative Action was repealed by the Supreme Court. The landmark ruling was a watershed moment in how we think of race and social mobility in the United States. But for high schoolers, the crux of the case lies somewhere else entirely.

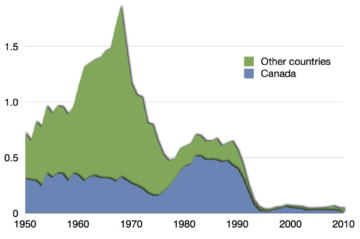

Arguably the greatest global health policy failure has been the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) refusal to promulgate any regulations to first mitigate and then eliminate the healthcare industry’s significant carbon footprint.

Arguably the greatest global health policy failure has been the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) refusal to promulgate any regulations to first mitigate and then eliminate the healthcare industry’s significant carbon footprint.