by Richard Farr

I will use this column to defend myself against the accusation, first made by my surgical assistant Mr. Alan Turing, that I was negligent in the death of an individual under my medical care. Or, as one armchair prosecutor has said, that I am “a stereotypically British sentimentalist who thinks dogs are more human than people.” The story is an ugly one but the facts are straightforward.

I will use this column to defend myself against the accusation, first made by my surgical assistant Mr. Alan Turing, that I was negligent in the death of an individual under my medical care. Or, as one armchair prosecutor has said, that I am “a stereotypically British sentimentalist who thinks dogs are more human than people.” The story is an ugly one but the facts are straightforward.

It was about 3 AM on a winter’s night in the small town of ________ . The only other neurosurgeon in the area had become “too ill to travel home” while vacationing on Maui. (From her voice message I was immediately able to diagnose Margarita Syndrome, with possibly an enlarged Piña Colada.) Anyway I was the only sawbones available when the call came in: CODE BLUE, DOC. ROAD ACCIDENT. FOUR VICTIMS WITH HEAD INJURIES. WAKEY WAKEY.

In my line of work you don’t shock easily, but I was about to have the most disturbing night of my life.

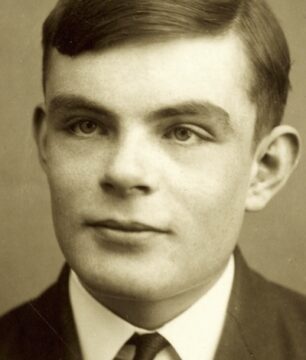

I should pause here to explain an important background detail. Turing, who had sent the message, was only moonlighting at the hospital. He was a quick learner for sure, if a bit of an oddball, and his daytime preoccupation (I hesitate to call it an occupation) was a Ph.D. in computational philosophy, whatever that is. He was competent enough; I only wished he wouldn’t keep urging me to read his draft material, which I found either impenetrably technical or else a jocose, badly written muddle. One particular essai of the latter kind turns out to be somewhat relevant to the ludicrous stand he has taken in the present matter. It begins with the arresting first sentence: I propose to consider the question, “Can machines think?” and progresses only pages later to the blithely contradictory The original question, “Can machines think?” I believe to be too meaningless to deserve discussion. (“Fascinating,” I said, hoping that was diplomatic enough.)

When I got to the clinic, several comatose forms already lay on gurneys in our small operating theater. The victims’ heads had been wrapped in temporary bandages by the paramedics; even when those came off, the first three individuals were such a mess that they were not immediately recognizable. However I noticed at once an amazing coincidence — so amazing in fact that it gave me an uncanny feeling, as if instead of attending to a real emergency in a real hospital I was trapped inside one of those sophomorically simple fictions on which, as I had discovered from coffee break conversations with Alan, philosophers like to exercise their limited imaginations. All three figures had virtually identical contusions; all three seemed to be in immediate danger of dying; all three were returning to consciousness and groaning as if with one voice: “I want you to stop the pain!”

A surgeon under time pressure can get tunnel vision. You’re so concerned with identifying the medical specifics that you don’t see the big picture. So it took a few minutes before I stood back and really looked at the faces of the victims. Oh horror.

These were not random motorists! These were Hugh, Allie, and Rob, three of my closest friends. I turned away in shock, and only then remembered the fourth gurney. The blanket was smaller than the others and the face under the bandages —

“Alan! This is a dog! Why did you bring in a dog?”

“It was in the same car. And it’s a victim too, isn’t it?” He glared at me, as if testing me. “Isn’t it?”

I wiped away some of the blood matting its fur. It was Rob’s dog, of course.

“Misfit!”

“There’s no need to be rude.”

“No no, Alan, not you. That’s the dog’s name. Misfit.”

Let me be clear. I had known these three people (and the dog) for years. They were, on the one hand, completely distinct individuals. I might have said for example (or rather not said, but thought) that Allie ranked higher than Hugh or Rob in raw intelligence, and perhaps lower in empathy and practical life skills, or that Rob was more adventurous, and best with children because of his patience and playfulness, or that Hugh was the only natural athlete among them, and had a better sense of humor and a passionate hatred of broccoli. Or that Misfit was amazingly smart for a dog and a very pleasant companion. In one sense though, all were the same: likable, high-functioning examples of their kind.

Well. Rather than wasting your time with the anatomy-class details (fracturing of the cerebrospinal X with massive swelling in the parietal Y, that sort of blather) I will say only that emergency surgery on each was immediately indicated. Also I was in danger of being distracted by their groaning —

(Hugh: “I want you to help me!” Allie: “I don’t want to die!” Rob: “I want the pain to stop!” Misfit: “Awooooo!”)

— so I put them all under, got Turing to fire up my best circular saw from the 50% OFF bin at DiscountHomeRepair, and went to work.

Oh double and triple horror.

As soon as their brains were exposed, something very strange was apparent. Let’s start with the simple cases. As it had never for a moment occurred to me to doubt, Hugh was an anatomically normal example of Homo sapiens, his gray matter familiar in every way. And Misfit was equally clearly a genuine Canis lupus familiaris.

But then there was Allie. She had a brain, for sure. It and she were clearly organic: I was looking at a naturally evolved organism. But her brain was not a human brain. It had six lobes, glowed a purplish blue, and shifted around on its own in an inappropriate way, like a muscle. Allie had been doing a good job of fooling everyone but there was no doubt now: she was an alien.

Rob’s case was if possible even more disconcerting. What I found inside his skull (made from a metallic substance that ruined a perfectly good $30 blade) was even harder to make sense of at first. It wasn’t anything I could call a brain; it wasn’t natural in that sense. There were wires, microscopic welds, and little hexagonal objects that might have been chips except that they shimmied and winked and kept rearranging themselves in different geometric patterns. Rob was indubitably a product of technology — a manufactured object. Like Roy Batty in Blade Runner, Data in Star Trek, Eva in Ex Machina (and on and on), he was a robot.

A seemingly irrelevant thought hijacked my own brain at this point, perhaps as a defense mechanism against panic. “Wow!” I thought. “Hugh, Allie, and Rob certainly all aced that “test” Alan keeps wittering on about. In all the years I’ve known them, it has never crossed my mind that they’re not human beings, even though only one of them is!” And then I thought: “Funny. Misfit aced the test as well, didn’t she? Sort of?”

Hugh happened to be closest to me and I started working on him immediately. At least with him I knew what I was doing. Then — instinctively, without so much as making a call to the Consulting Hypothetical Ethicist hotline — I turned to Allie. The unfamiliar anatomy meant my confidence was lower; on the other hand I felt it was likely that if I could simply prevent further loss of her chartreuse-toned day-glo “blood” then things might turn out OK. The brain tissue itself looked very little damaged, and indeed if my eyes didn’t deceive me it was already busy repairing itself. Not wanting to get into an argument with Hippocrates — primum non nocere — I patched her up and mentally crossed my fingers.

That’s when things got sticky.

Hugh and Allie were still out cold. But Misfit started howling again and at that very moment Rob opened his eyes and cried “I want you to help me! I want the pain to stop! I want chocolate ice cream with nuts on top!” Finally, with pitiful, pleading eye contact: “Richard, my old friend, I want you to save me! Pleeeease!”

Turing’s testimony is accurate, I don’t deny: despite his protests I ignored Rob, checked again on Allie, and turned next to Misfit. When Misfit was out of danger I turned back to Rob, but he was already dead.

Or as I prefer to say: he was doing as excellent an imitation of being dead — but then he had only ever been doing an imitation of being alive.

This is where Alan and I part company.

“You’re prejudiced.”

“Nonsense.”

“You’re a racist.”

“Bullshit.”

“OK then a speciesist.”

“Malarkey.”

Allow me to make a point about my deliberations in the following slightly unusual way. All four of these victims behaved as if they had genuine wants. And though it might seem that I acquired the belief that they all had genuine wants from that behavior, actually I did not acquire the belief in that way.

In recent days, while waiting to hear whether I’ll have my medical license revoked, I’ve had little to do. (My colleague returned from Maui with shaky hands and bags under her eyes but has taken over the clinic again.) So I’ve had time to read the draft paper by Turing that I’d merely skimmed earlier. In a section titled “The Argument from Consciousness” he says:

This argument is very well expressed in Professor Jefferson’s Lister Oration for 1949, from which I quote. “Not until a machine can write a sonnet or compose a concerto because of thoughts and emotions felt, and not by the chance fall of symbols, could we agree that machine equals brain-that is, not only write it but know that it had written it. No mechanism could feel (and not merely artificially signal, an easy contrivance) pleasure at its successes, grief when its valves fuse, be warmed by flattery, be made miserable by its mistakes, be charmed by sex, be angry or depressed when it cannot get what it wants.”

This argument appears to be a denial of the validity of our test. According to the most extreme form of this view the only way by which one could be sure that machine thinks is to be the machine and to feel oneself thinking. One could then describe these feelings to the world, but of course no one would be justified in taking any notice. Likewise according to this view the only way to know that a man thinks is to be that particular man. It is in fact the solipsist point of view. It may be the most logical view to hold but it makes communication of ideas difficult. A is liable to believe “A thinks but B does not” whilst B believes “B thinks but A does not.” Instead of arguing continually over this point it is usual to have the polite convention that everyone thinks.

Here’s the thing, though. “That everyone thinks” is not a “polite convention” — it’s the only plausible theory given the evidence, once you stop misunderstanding what the evidence actually is.

The evidence works like this. First, and crucially: I know for certain that I am a good example of a being with genuine wants, and I know this because of my thrillingly direct acquaintance with my own wants: I have them. (So far, so Descartes.) Second: I lack this direct acquaintance with the wants of others, so I could be what Alan calls a solipsist — but solipsism is strictly for the rubes. We are post-Darwinian. As Alan himself concedes, it remains a mystery exactly how an evolved physical entity like my body can sustain the inner world of wanting that I directly experience, but it certainly does so, at least in my case. Third, that fact constitutes excellent grounds for assuming that other sufficiently similar evolved entities sustain a similar inner world and thus also have genuine wants.

To summarize: I didn’t believe that Hugh truly wanted what he said he wanted because of his verbal behavior. That could have been imitated with high fidelity by a voice recorder. I believed it because that verbal behavior’s source was an evolved entity sufficiently like me.

Both Allie and Misfit are much less like me than Hugh. But their behavior comes from closely analogous sources. I cannot know the exact texture of Hugh’s inner life; much less can I know the texture of Allie’s or Misfit’s. But to conclude therefore that they have no genuine wants is, in the Darwinian circumstances, an assumption so extravagantly baseless that only a philosopher on their lunch hour could entertain it.

Rob, though: ah! Here we have exactly the opposite problem. If Rob had been made from cogs and gears and string, even a fanatic technophile like Alan would not expose himself to ridicule by accusing me of wrong-doing. Nor would he, I think, if Rob had been made from our own familiar servos and silicon, with maybe an Apple logo thrown in for good measure. In those cases, however convincing the behavior, most people would accept as obvious that Rob was not a man but a marionette, not a guy but a gimmick — that, even though he could pass the “test” by behaving like he had genuine wants, those wants were no more real than the wants a child might ascribe to a wind-up doll with a key in its back.

“Ah,” Turing has already said to you — over-impressed by clever engineering as always — “but this technology was different. Far more sophisticated. Far beyond anything we understand. Probably Allie created it!” (This turns out to have been true.) “On what grounds can we say that such perfectly manufactured intelligence is not real intelligence?”

Here I think lies Turing’s fundamental muddle. He has achieved the no doubt valuable insight that a certain kind and level of artificial intelligence — a good enough imitation of intelligence — just is intelligence. But he then moves gleefully, with little thought and diddly-squat by way of argument, to the radically false and, in this age of increasingly persuasive simulacra, profoundly dangerous conclusion that a good enough imitation of wanting just is wanting. It’s not wanting; it’s not even some evidence of wanting; in itself, it’s exactly no evidence of wanting.

Is my conclusion then that we know Rob’s wants were not genuine? Not quite so fast. My conclusion is only that his revealed nature forces us to recast the “evidence” derived from his behavior, and that in this new context it turns out to be irrelevant. From which it follows that I had strong and urgent grounds for ignoring his “wants” in favor of the genuine ones expressed so eloquently by Allie and Misfit.

Chess World Champion Garry Kasparov had an interesting response to playing and being beaten by the computer Deep Blue in 1997: he spoke of it as having a very human intuition, including “a sense of danger.” Like so many people confronted with artificial intelligence, he didn’t seem to see — or at least was profoundly tempted to ignore — the dull possibility that evidence about how the machine behaved was not even a poor guide, but rather was no guide at all, to what was, as it were, actually going on.

I’m sorry Rob “died,” but only because I lost a “friend” and Misfit lost her “companion.” (We both feel a little better now that I have adopted her and am feeding her too many treats.) I’m not in the least sorry for Rob; I did the right thing. In short, Turing’s ideas in this area are catnip to the gullible and a moral menace. Perhaps he should take up cryptography. I rest my case.