by Claire Chambers

The writer Tabish Khair was born in 1966 and educated in Bihar before moving first to Delhi and then Denmark. He is the author of various acclaimed books, including novels The Thing About Thugs, How to Fight Islamist Terror from the Missionary Position, and Just Another Jihadi Jane. He has also published poetry collections such as Where Parallel Lines Meet and Man of Glass. Khair’s academic writing includes studies of alienation in contemporary Indian English novels, the postcolonial gothic, and the new xenophobia.

The writer Tabish Khair was born in 1966 and educated in Bihar before moving first to Delhi and then Denmark. He is the author of various acclaimed books, including novels The Thing About Thugs, How to Fight Islamist Terror from the Missionary Position, and Just Another Jihadi Jane. He has also published poetry collections such as Where Parallel Lines Meet and Man of Glass. Khair’s academic writing includes studies of alienation in contemporary Indian English novels, the postcolonial gothic, and the new xenophobia.

In addition is Quarantined Sonnets, a sequence about Covid-19 published soon after the virus went global. In this slim volume, Khair rewrites Shakespearean sonnets with humour as well as pathos in order to examine ageing, sexuality, and other subjects. Twenty-one Shakespearean sonnets are reinterpreted to reflect the changing face of love and mortality amid health disaster. Above all, the poetry collection examines how economies are impacted by the virus, and satirizes rampant capitalism against the backdrop of the Covid-19 pandemic. Khair does something similar in his most recent novel The Body by the Shore, for which I wrote a ‘Reader’s Guide’ and so I will not say too much about it here. In both his poetic and fictional works he sends shots across the bow against materialism, corporate greed, and social inequality.

Similarly, at least two stories from Khair’s 2023 collection Namaste Trump, ‘Shadow of a Story’ and, especially, ‘Namaste Trump’, have coronavirus as a fulcrum. The narrator of ‘Shadow of a Story’ is angered by India’s plight amid the 2021 catastrophe of ‘pyres burning, bodies floating down the Ganges during the pandemic’ (167).

The titular tale ‘Namaste Trump’ is set earlier on, around the time of the American president’s state visit to India in February 2020, and examines the onset of Covid. The story centres on a young servant with physical and mental disabilities, employed under near-feudal conditions by a wealthy Hindu Right family. As Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s migrant labour crisis escalates, the family sends the boy back to his village in Bihar. Disconnected from his supposed home and attached to the metropole, Chottu flees to live among marginalized city-dwellers. Eking out an existence in a nearby dump, he contracts the virus there and goes on to die from it. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Rain. Hund Riverbank, Pakistan, November 2023.

Sughra Raza. Rain. Hund Riverbank, Pakistan, November 2023.

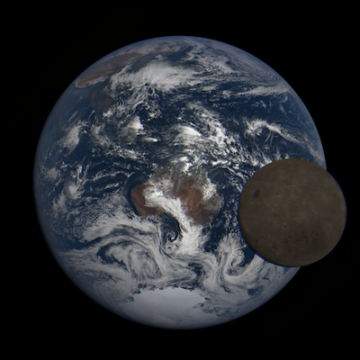

In the 21st century, only two risks matter – climate change and advanced AI. It is easy to lose sight of the bigger picture and get lost in the maelstrom of “news” hitting our screens. There is a plethora of low-level events constantly vying for our attention. As a risk consultant and

In the 21st century, only two risks matter – climate change and advanced AI. It is easy to lose sight of the bigger picture and get lost in the maelstrom of “news” hitting our screens. There is a plethora of low-level events constantly vying for our attention. As a risk consultant and  The first time I became aware of Friedrich, many years ago, I was in Zurich to meet an elderly Jungian psychoanalyst—my head stuffed with theoretical questions and eerie dreams with soundtracks by Scriabin. Walking down the Bahnhofstrasse, I passed a bookstore window displaying a stunning art book with the elegant title Traum und Wahrheit (Dream and Truth) and a simple subtitle: Deutsche Romantik. I didn’t yet speak German, but I knew enough to be interested. The book was too heavy for my luggage. I bought it anyway and had it shipped.

The first time I became aware of Friedrich, many years ago, I was in Zurich to meet an elderly Jungian psychoanalyst—my head stuffed with theoretical questions and eerie dreams with soundtracks by Scriabin. Walking down the Bahnhofstrasse, I passed a bookstore window displaying a stunning art book with the elegant title Traum und Wahrheit (Dream and Truth) and a simple subtitle: Deutsche Romantik. I didn’t yet speak German, but I knew enough to be interested. The book was too heavy for my luggage. I bought it anyway and had it shipped. What lured my eye to the cover as I passed by was a partial view from one of my now favorite Friedrich paintings, Das Große Gehege (The Great Enclosure)—a cool marshy landscape evoking real ones I would later see from train windows. How could just a corner of a painting have such power? It was the light, the late afternoon saturation of yellow, the black shadowed trees, and the hint of evening gloom already visible as gray on the horizon even though the sky above was still blue. I was captivated.

What lured my eye to the cover as I passed by was a partial view from one of my now favorite Friedrich paintings, Das Große Gehege (The Great Enclosure)—a cool marshy landscape evoking real ones I would later see from train windows. How could just a corner of a painting have such power? It was the light, the late afternoon saturation of yellow, the black shadowed trees, and the hint of evening gloom already visible as gray on the horizon even though the sky above was still blue. I was captivated.

Because I have taken some medical leave from 3QD in the past few weeks, we have not had magazine posts for a while, though we have continued to post curated articles in the “

Because I have taken some medical leave from 3QD in the past few weeks, we have not had magazine posts for a while, though we have continued to post curated articles in the “

Many decades ago, I was fortunate to have had the opportunity of living in India for several years. I was enthralled by that country: its cultural richness; the environment; the food, but most of all the friendliness and warm hospitality of its diverse people. There were, of course, issues that confounded me and stark contradictions stared back at me from many directions, but of particular concern was the scale of the poverty amongst vast sections of the population, an issue that visited me at home frequently. A small begging community gathered regularly at my front gate, hungry and calling out for food. As my knowledge of the Indian social structure deepened, I came to understand that these people belonged to the most oppressed castes in Indian society and not only they, but a multitude of others were living in poverty, and with hunger.

Many decades ago, I was fortunate to have had the opportunity of living in India for several years. I was enthralled by that country: its cultural richness; the environment; the food, but most of all the friendliness and warm hospitality of its diverse people. There were, of course, issues that confounded me and stark contradictions stared back at me from many directions, but of particular concern was the scale of the poverty amongst vast sections of the population, an issue that visited me at home frequently. A small begging community gathered regularly at my front gate, hungry and calling out for food. As my knowledge of the Indian social structure deepened, I came to understand that these people belonged to the most oppressed castes in Indian society and not only they, but a multitude of others were living in poverty, and with hunger.

Chakaia Booker. Romantic Repulsive, 2019.

Chakaia Booker. Romantic Repulsive, 2019.