by Derek Neal

I was in Toronto the other day to see Paul Schrader’s newest film, Oh, Canada, which was screening at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). This was my first time seeing a movie at a festival, and the experience was quite different from seeing a movie at a cinema: we had to line up in advance, the location was not a cinema but a theatre (in this case, the Princess of Wales Theater, a beautiful venue with orchestra seating, a balcony, and plush red carpeting), and there was a buzz in the air, as everyone in attendance had made a special effort to see a movie they wouldn’t be able to see elsewhere. As I stood in line with the other ticket holders, I noticed that there was a clear difference between the type of person in my line, for those with advance tickets, and the rush line, for those without tickets and who would be allowed in only in the case of no shows: in my line, the attendees were older, often in couples, and had the air of Money and Culture about them; in the rush line, the hopeful attendees were younger, often male, and solitary. In other words, those in the rush line, the ones who couldn’t get their shit together to buy a ticket in time, could have been typical Schrader protagonists: a man in a room, trying, yet frequently failing, to live a meaningful life, to keep it together, to be the type of person who buys a ticket in advance, and invites his wife, too. Yet there I was, in the advance ticket line: a man, relatively young, and someone who spends a good deal of time by himself. I’d invited my partner of 10 years, but she didn’t come because she doesn’t like Paul Schrader films, and who can blame her? They’re not for everyone. Perhaps my presence in the advance ticket line, but my understanding of and identification with those in the other line, helps explain my deep attraction to Schrader’s films: I know his characters, and in the right circumstances, I could become one of his characters.

I was in Toronto the other day to see Paul Schrader’s newest film, Oh, Canada, which was screening at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). This was my first time seeing a movie at a festival, and the experience was quite different from seeing a movie at a cinema: we had to line up in advance, the location was not a cinema but a theatre (in this case, the Princess of Wales Theater, a beautiful venue with orchestra seating, a balcony, and plush red carpeting), and there was a buzz in the air, as everyone in attendance had made a special effort to see a movie they wouldn’t be able to see elsewhere. As I stood in line with the other ticket holders, I noticed that there was a clear difference between the type of person in my line, for those with advance tickets, and the rush line, for those without tickets and who would be allowed in only in the case of no shows: in my line, the attendees were older, often in couples, and had the air of Money and Culture about them; in the rush line, the hopeful attendees were younger, often male, and solitary. In other words, those in the rush line, the ones who couldn’t get their shit together to buy a ticket in time, could have been typical Schrader protagonists: a man in a room, trying, yet frequently failing, to live a meaningful life, to keep it together, to be the type of person who buys a ticket in advance, and invites his wife, too. Yet there I was, in the advance ticket line: a man, relatively young, and someone who spends a good deal of time by himself. I’d invited my partner of 10 years, but she didn’t come because she doesn’t like Paul Schrader films, and who can blame her? They’re not for everyone. Perhaps my presence in the advance ticket line, but my understanding of and identification with those in the other line, helps explain my deep attraction to Schrader’s films: I know his characters, and in the right circumstances, I could become one of his characters.

We made our way into the theatre and found our seats. I’d put some thought into my choice of assigned seat. It was one of the cheapest seats, but it was also the final row of the dress circle, just below the balcony, and it was almost at the end of the aisle. I thought this would give me a good view of the screen while also allowing for easy entry to and exit from my seat, avoiding the need to stand up to let people pass while also removing the need for me to squeeze by people in my row. However, as the usher showed me to my seat, I realized I had not, in fact, made a good choice.

Rather than being at the end of a row of seats, my place was next to a wall that jutted out in front of me and entered my peripheral vision. The seats that I thought would be next to me, that I had seen as greyed out on the Ticketmaster website, were actually those in the balcony above me. I could still see the full screen, but if I shifted just a little to the right, or leaned back, the wall began to obstruct the screen. I realized, with some dismay, that those in the rush line, should they gain entry, would certainly end up with better seats than me, and that the categorization I’d made in my head of possible Schrader protagonist fuck ups, on one hand, and people who have it all figured out, on the other, was false. The smug self-satisfaction I felt disappeared as quickly as it had come—while I had successfully infiltrated the advance ticket holder line, I was an imposter, and my misguided seat choice had revealed my true identity.

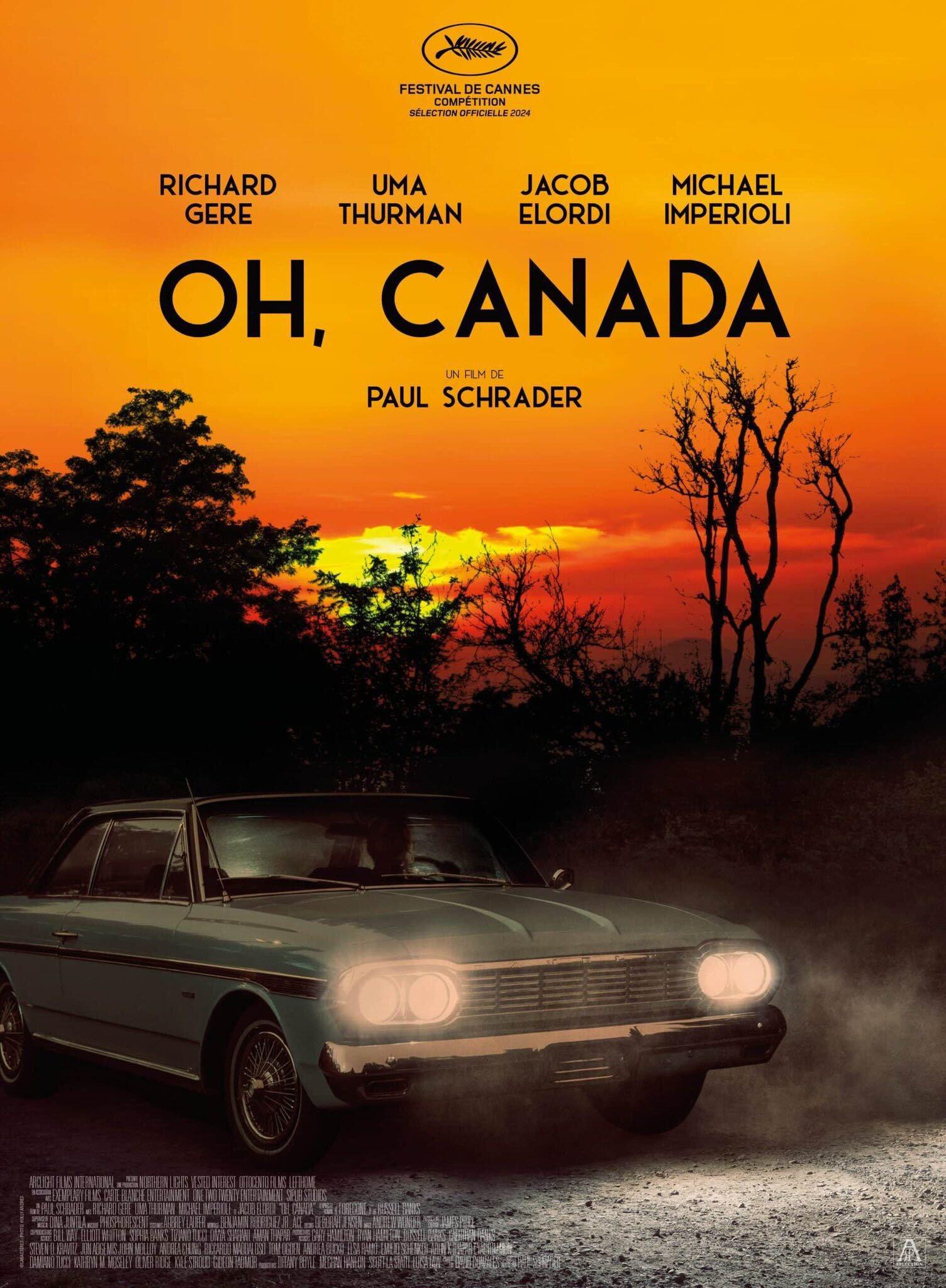

After an interminable number of messages from the corporate sponsors of TIFF—RBC, Rogers, Visa, Dyson—and a Land Acknowledgement that mentioned being “grateful” to work on the lands now known as Canada, as if the land had been peaceably gifted, rather than violently seized, the film began. The screen lit up with a credit sequence showing a film crew setting up cameras, lighting, and microphones in a room of Leonard Fife’s (played by Richard Gere) house. In the movie, Fife is an acclaimed documentary filmmaker who is known for exposing sordid political truths—the testing of Agent Orange by the American military in Canada, the residential school system, some sort of fishing or hunting scandal. The details of his career are not fleshed out, but the message is clear: Fife is a truth teller and a political darling. Now his former students have come to make a documentary about him, the final flourish in a remarkable career and a sort of hagiography. In the room next to where the documentary will be shot, we see Fife in bed. He is old and sick, and the image of Gere’s face is shocking, ravaged by cancer and chemotherapy. As I sat watching these images, I was intrigued: Schrader seemed to be creating a film within a film, and he’d turned Gere’s image on its head—no longer the sex symbol created by American Gigolo, but the bedridden old man, who needs a personal support worker to wipe him after he uses the bathroom. However, I was also slightly perplexed. Behind these images played a sort of uplifting, folk-pop music that sounded kitsch and twee, the kind of music one might expect in a Hallmark movie, but not in an emotionally complex Schrader film.

The film within a film begins and we soon learn that Fife has decided to use the occasion as an opportunity to finally tell the truth about his life, much to the surprise of the filmmakers and his wife, Emma, who is played by Uma Thurman. Fife, it turns out, is not the morally upright man he’s claimed to be all these years, but rather a man who has run away from responsibility at every turn. Thus begins a series of flashbacks and voiceover that make up a large part of the film. We see Gere in his wheelchair; we hear him talk; and then we go back in time to the events of his life. In these flashbacks, Fife is played by Jacob Elordi, except that sometimes he isn’t, sometimes Gere himself is in the flashback, looking much better than in the present, but still playing a supposedly 22-year-old man. There are no technological tricks here of the sort used in The Irishman; instead, the point seems to be that we are seeing Fife’s memories, and in his memory, he may be imagining himself as he is now, but in the events of the past. The effect is destabilizing on the viewer, but as a representation of a person’s memory, it works, and it drives home the point that we cannot trust anything Fife says: what if his attempt to destroy his reputation is based on a fabrication, rather than the honest confessions of a dying man, or what if he is simply too sick to remember things coherently?

Scenes occasionally repeat themselves or contradict one another. Fife claims that he dropped out of college and went to Cuba, then that he never made it to Cuba, but instead met a woman and possibly impregnated her. Why he was interested in Cuba in the first place is unclear. He then meets another woman, leaves the first woman, then leaves the second woman and somehow gets a teaching job at the University of Virginia (even though he may have dropped out of college). He then gets married and has a child, but decides he wants to move to Vermont and teach there, instead. The women’s names all start with A. Are they the same woman? Who knows? Elordi enters a café in Vermont, then later, Gere enters the same café in his memory. All the people from his past appear on the barstools next to him. None of this makes any logical sense, which is fine. Schrader seems to be attempting to communicate the story of Fife on a psychological level rather than a realist one. The attempt is admirable, and one feels that Schrader has taken a big swing here, but he doesn’t connect. In other examples of films that play with memory and time—I’m thinking of Tarkovsky and Antonioni—one also struggles to coherently summarize the events of the film, but the experience of viewing the film is its own reward, and even if we can’t explain what the film means, it speaks to us on an intuitive level. That doesn’t happen in Oh, Canada.

In addition to the muddled plot, the stylistic choices are also experimental, but without any underlying coherence. The shots in the present are done in 4:3 aspect ratio, which immediately signals that we are in the presence of an auteur, while the shots in the past are in widescreen. This works to formally distinguish the two timelines, but then Schrader pushes things further: when we are in the past of the past timeline, meaning when Fife is in college, the scenes are in black and white, and even though it is meant to be the 60’s, it feels as if we are watching a film from the 40’s. The intended effect, apart from confusion, is unclear. Combined with all this is the recurring pop-folk soundtrack, which creates a feeling of cheap sentimentality. There is also the use of voiceover, but whereas in past Schrader films voiceover has served to give the film a guiding moral consciousness, here we have two different characters providing voiceover, both Fife and his estranged adult son.

Schrader has often talked about his philosophy of screenwriting, which is to take a personal problem he has and create a metaphor that represents the problem. The making of the film then solves his problem. Schrader has also said that his biggest failures have come when he fails to distance the material enough from himself, when he doesn’t create a metaphor but simply treats the problem itself as the material of the film. That seems to be the case here. Leonard Fife is an old filmmaker who knows he doesn’t have much time left, and it pains me to say this, but the same is true of Schrader. So, where’s the metaphor? It would seem to be in the story of the young Fife and his escape to Canada. We learn that Fife is viewed as a hero in Canada because he crossed the border to escape being drafted in the Vietnam War, but Fife tells us that this is false. Instead, while in Vermont, he learns that his wife in Virginia has miscarried. He also sees the deterioration of his friend’s marriage, and he feels the pressure of his father-in-law, who has asked him to take over the family business, but whom he plans to turn down. All these responsibilities seem to be too much for Fife; he simply crosses into Canada to start a new life and to escape his old one. Canada, then, becomes an extension of the United States in the American imagination, an addition to the frontier; when one can no longer go West, one goes North to reinvent oneself and to make a buck. Here is the metaphor, and if this were the movie, it might have been a good one. Schrader’s successful films, such as First Reformed, Light Sleeper, or Affliction, are small films. They are about one man, with one job, in one place. A film about Fife’s deteriorating marriage, or his struggles as a professor, and his subsequent journey to Canada as means of escape, would have been a recognizable Schrader film. But this film is too unwieldy for him to control. With all the characters, timelines, and plot points, the film has no center and no unity.

After the screening was over, I sat in my seat until the lights came up and the ushers asked the remaining patrons to leave. Then I loitered in the lobby for a while, wondering what to do with myself. I’d expected so much, and now I was disoriented, confused as to how Schrader could have misfired so badly. I decided to go to my favourite bar in Toronto, which is modeled on a Japanese listening bar, meaning it has an extremely high-quality sound system, vinyl records, and dark wood paneling. This one even has paper sliding doors. I sat at the bar by myself, ordered a highball, and began typing this essay in the Notes app on my iPhone. “Summer Madness” by Kool & the Gang wafted out from the speakers, and the mixture of sound and candlelight created a warm, expectant atmosphere. It wasn’t crowded. After a while, the owner came by and dropped off a dish of wasabi roasted green peas for me to munch on. I sipped my highball, popped the peas into my mouth, and tapped away. When I finished the highball, I looked up from my phone and noticed the bar had begun to fill up. It wasn’t late yet, but the energy had begun to change. There were groups of people rather than couples, and the music had gone from the deep ambience of Kool & the Gang to something more upbeat. Soon, there would be dancing, and I thought about ordering another highball, losing myself in the music, seeing where the night would take me. I had other concerns—the fact that I had to drive home, the fact that someone was waiting for me—but the atmosphere of the bar had begun to make me lose sight of that, the way the best bars and clubs do, by acting as a sort of portal to another dimension where another life, another existence is possible. What would Willem Defoe in Light Sleeper do, I wondered. What would Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver do? What would Oscar Isaac in The Card Counter do? What would the men in the rush line do? The waitress came over and asked me if I wanted another, but I asked for the bill instead, left a good tip, then went outside and walked around the block for a while to clear my head and reacclimate myself to the city rather than the alternate universe of the Japanese bar. I got in my car and drove home.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.