by Brooks Riley

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Nils Peterson

The Christmas song we all know has got it all wrong. “Better watch out, Better not cry, Better not pout, I’m telling you why, Santa Claus is coming to town.” This turns his gifts into a payoff. You do this and you’ll get that. It’s salary. But a gift isn’t salary. A gift is like grace, something you are given, not something you have earned or deserve. That’s where the real Santa comes in. He wants to give you something because you’re part of creation and you’re you. Indeed, the creation is one of his gifts.

CFO’s have taken over Christmas and tried to make a gift part of their accounting department. Their carrot and stick: if you don’t act right you won’t get gifts. The sense is that if you aren’t deserving, deserving meaning acting the way they think you should act, you won’t get anything, or, maybe, a lump of coal in your stocking while sister gets an orange. But Santa is better than that. The world is better than that.

Christmas morning. I wake early

to a strange noise from below,

and, in my footed pajamas, holding

on to the railing, I creep down the

shadowy stairs leading from the

chauffeur’s flat to the workroom

below. Of all things, there’s my

father bending over an electric train

whizzing round and round an oval

track nailed to a piece of plywood.

He doesn’t see me, but I watch him

caught as he is in the mystery of train

lights, ruby and white, circling in

the half-darkness. For awhile I don’t

make a sound, but watch him,

wondering about his strange smile.

All these years later, I tiptoe down

the stairs again, now understanding

the poverty of his childhood

and the jobless years of the Depression,

and I watch him and imagine him thinking –

I am able

to give to my children,

for Christmas,

this wonder.

P.S. The song, though it doesn’t know it, has one line we need to appreciate – “So be good for goodness sake.” Think about it. N

the year is a road

that turns on its way

where we are seems clear

and maybe next day

but then in its going

it bends out of sight

we follow its flowing

with all our unknowing – NP

“Ye shall have a song … and gladness of heart.”

The thought comes from Isaiah, “Ye shall have a song, as in the night when a holy solemnity is kept; and gladness of heart, as when one goeth with a pipe to come into the mountains of the Lord.”

So not only a song, but a particular kind of song – an “as in the night when a holy solemnity is kept” kind of song, not only gladness, but a particular kind of gladness – an “as when one goeth with a pipe” kind of gladness. And if you “goeth” you must be heading somewhere. The text says, “to come into the mountains of the Lord.” Wherever you find your “mountains of the Lord,” you’d want go there carried by the joy of your own music.

I first met this verse more than 70 years ago singing Randall Thompson’s Peaceable Kingdom with my old college choir. I can close my eyes and sing it again with my friends, auld lang syne indeed. And remembering further, here’s the text of almost the penultimate song of that piece, also from Isaiah, “The paper reeds by the brooks, by the mouth of the brooks, and everything sown by the brooks, shall wither, be driven away, and be no more.” It too is a marvelous in its dark, descending chords and thoughts. Wonderful music to sing, but “Ye shall have a song and gladness of heart” answers the darkness with a fine antiphonal eight-part chorale full of joy and gladness, gladness of heart. Isn’t that the best gladness? “Gladness of heart.”

My New Year’s Wish for Us All, “Ye shall have a song … and gladness of heart,” No, I should say “We shall have a song…and gladness of heart.”

A New Year’s Question. Coleman Barks in his book The Scrapwood Man asks “I would like to know what you have escaped, how you slipped free from some compulsion or inherited condition. What moved your story along?”

“What moved your story along?” A great question to ask at the beginning of a new year and to think about now and again as the year winds on its way.

Sughra Raza. Cambridge In The Charles, December, 2024.

Sughra Raza. Cambridge In The Charles, December, 2024.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Azadeh Amirsadri

I will be in Strasbourg, France during Christmas this year, spending time with my 96 year old father who talks about his mother, my mother, and his cousins, all gone now, but seemingly alive to him. Strasbourg, as beautiful a city as it is, has always been a bittersweet place for me, from my childhood when I went to kindergarten there until now. Good and bad memories merge in a city known for its gothic cathedral, Christmas market, Rhine Valley wine, and specialty cuisine.

I will be in Strasbourg, France during Christmas this year, spending time with my 96 year old father who talks about his mother, my mother, and his cousins, all gone now, but seemingly alive to him. Strasbourg, as beautiful a city as it is, has always been a bittersweet place for me, from my childhood when I went to kindergarten there until now. Good and bad memories merge in a city known for its gothic cathedral, Christmas market, Rhine Valley wine, and specialty cuisine.

I lived in Strasbourg from the age of six to nine, and that was the first time I experienced Christmas. There was a woman, Mademoiselle Simone, who worked in my younger sister’s preschool that my parents had befriended. She would visit us in our home or she would have us over at her parents’ house, where they showed us a porcelain cup that had a bullet hole in it from the second world war, or maybe the cup is something I created in my mind. One year, she took us to the beautiful Cathedral of Notre Dame in Strasbourg for Christmas Eve. I don’t remember my parents being there with us, because we had that no-parents-around energy and we felt special to be there with her. I remember a lot of people inside and outside the huge cathedral, and worrying about getting lost in that crowd as she told us to hold hands. I also remember the lights, candles and music, and sweet Mademoiselle Simone who gave us each chocolate and an orange.

We went back to Iran when I was nine years old, and I secretly liked Christmas and envied anyone who was lucky enough to be in a family that celebrated it. I had two Christian friends in school, both Assyrians, who put up Christmas trees at their house. I would go over and admire their green trees with silver garlands, red ornaments, and a star or angel on top. A few pop-up stores sold fresh trees and tall red statues of Santa Claus, or Baba Noel as we called it. It all looked so magical to me and I envied my friends’ holiday that was special to them only. I also loved Nowruz, the Iranian New Year, but everyone got to celebrate it which made it not as special as Christmas in my preteen mind. Read more »

If you talk about it, it’s not Tao

If you name it, it’s something else

What can’t be named is eternal

Naming splits the eternal to smithereens

………………… —per Lao Tzu, poet, 6th Century BC

_____________________________________

At first I think, I’ve got it!

Then I think, oh no, that’s not it.

I think, it’s more like a flaming arrow

shot into the marrow

of the bony part of everything,

………. but some summer nights

………. it’s hanging overhead so bright

Then right there I lose it,

let geometry and time confuse it,

then it’s silent, it won’t sing a thing,

………. but some summer nights

………. it’s croaking from a pond so right

Then again, I lose it,

let theology and time confuse it,

then it’s silent and won’t sing a thing

………. I’m thinking I’ve been here before

………. feet two inches off the floor,

………. thinking, is this something true?

Sometimes I think I’ve lost it,

though I never could exhaust it

because it’s lower than low is,

and wider than wide is,

deeper than deep is,

higher than high is,

….……. but some fresh spring days

……….. it’s cuttin’ through the fog and the haze

I’m thinking I’ve been here before,

feet two inches off the floor, thinking

is this something true?

Jim Culleny, 7/15/15

Song rendition here: https://soundcloud.com/jim-culleny/lao-tzus-lament

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Mike Bendzela

During the twelve years I was a volunteer Emergency Medical Technician-Basic in my little town, I arrived onto scenes with patients suffering varying degrees of distress. I would first assess them, then help stabilize and package them for transport to the hospital; and if I was lucky, I would be assigned to drive the ambulance. It wasn’t that I minded assisting paramedics in the back with “bagging” (ventilating) critical patients or performing chest compressions on them; it was just that when the rig was rocking Code 3 on the way to the hospital, I was in danger of throwing up all over the floor in back. The medical term for this is kinetosis.

In those years I got to witness a fascinating phenomenon in a few patients who had suffered blunt force trauma to the head. Some patients who had not been rendered unconscious, and who were not so severely injured as to be completely incapacitated, existed, for a brief time, in a little window of reprieve–a period of grace, as it were.

Following trauma, a patient’s sympathetic nervous system fires up; the body is flooded with hormones such as adrenaline, and the capacity to feel pain diminishes. Most non-essential bodily functions are temporarily suspended, but the mind exists in a state of both intense excitation and preternatural calm. Perhaps this is a survival mechanism, evolution’s way of allowing an animal to keep its wits about itself long enough to crawl out of further harm’s way.

Our crew was called along with the sheriff to the scene of an adult male who had been bludgeoned with a baseball bat in bed by his wife, to whom he had served divorce papers. She then shot herself in the stomach with a revolver and called 9-1-1, claiming an intruder had attacked them. (Much of the background of this call came to us only weeks later.)

By the time we arrived, the wife-assailant was being treated by another crew, and our patient was sitting up on the edge of his bed, bloodied but conscious. He sat there quietly, leaning one elbow on his knee, the other arm cocked on his hip, and he looked at us with his head tipped to one side, as if listening to some music in the background. Read more »

by Mindy Clegg

Since the 2024 election, liberals, progressives, and the left has been wringing our collective hands over why Trump won yet again. Was it the racism, the misogyny, or the economy stupid? Was there some fraud happening behind the scenes? Was the Democratic party “too woke” or not “woke enough”? Did the Democrats ignore the common clay of the new west in favor of “they/them”? Did they lose the propaganda war? Was it people not voting or was it people voting, but against them? Do we blame white men, white women, Black men, Latinx voters or those who did not vote at all? Endlessly, on and on. Partisans of each explanation insist that they have the only real answer to the question of why Trump. But I would say that rather than singling out one reason as the answer, there are grains of truth in each.

Yes, people are struggling, even as the economy has been doing well. Yes, people did not vote for the obviously more qualified Black/South Asian woman because of misogyny and racism. Yes, the democratic party can be out of touch. Yes and more. History tells us that rarely is a single answer satisfactory in explaining events like this. But another I have not really seen is what role does nihilism play in the recent election. We know that trust in our shared institutions are at an all-time low across political divisions. While the roots of that are in the failures of those institutions, culture—especially culture lacking in political specificity but that positions itself as outside the mainstream—drove a commodified version of rebellion against our institutions. You can especially see this with the rise of “alternative” culture in the 1980s and 1990s. As such, Generation X took away a specifically nihilistic message that often provided no strong political sentiment. Many white Gen Xers seemed to have carried that worldview into the politics today, preferring a bomb thrower to political problem solver. That bomb thrower was seen as being more authentic, despite his obvious history of lying. Read more »

by Daniel Shotkin

This week, electors from across the country will cast their votes for the next president of the United States. Only now, more than a month after Election Day, will Uncle Sam officially wave goodbye to election season. That seasonal bout of incessant campaign mail and debate fever has found its way off the front pages, replaced by a national rumination over one question: How did we get here?

The overarching answer is that it depends on who you ask. The self-assured economist will tell you that Donald Trump’s election is simply the result of widespread dissatisfaction with inflation—“it’s the economy, stupid.” The zealous Middle East correspondent will point to Kamala Harris’ support of Israel’s actions in Gaza. The MAGA Evangelical will tell you Trump’s win was the direct result of divine intervention. As a poll worker, I have a slightly different take on the election. Instead of focusing on the results, I think we can learn more about the state of America in 2024 from Election Day itself.

To preface, I am not the most typical poll worker. As a high school senior, I signed up to work the polls through a program my school offered with the local town. Eight hours of light work with my friends for $200 was a great deal, especially since we would skip school. But the gravity of this particular gig hit full force during the mandatory four-hour training in our cafeteria—our instructor informed us that “our nation and democracy depend on you.” Quite a lot to ask of forty-odd chattering high school students.

By midday on November 5th, I walked to my assigned polling station unsure of what to expect. I had heard stories of election workers being threatened in battleground states, though I was skeptical of that happening in suburban New Jersey. Our instructor had also warned us to expect “challengers”—party officials inspecting voting procedure—watching our every move. After months of end-all, be-all election coverage, the only thing I felt sure of was that this election, more than any other, would be exceptional. My suspicions were confirmed as the polling station came into view. Read more »

by Mary Hrovat

It sounds like a parlor trick or gimmick, to walk 2,024 miles in 2024—trivial but harmless. It’s not like hiking the Appalachian or Pacific Crest Trail or climbing the highest peak on each continent, or running a marathon. But it is similar to a marathon in that the number involved is an arbitrary product of history that can somehow be useful for guiding a person’s efforts.

It sounds like a parlor trick or gimmick, to walk 2,024 miles in 2024—trivial but harmless. It’s not like hiking the Appalachian or Pacific Crest Trail or climbing the highest peak on each continent, or running a marathon. But it is similar to a marathon in that the number involved is an arbitrary product of history that can somehow be useful for guiding a person’s efforts.

The idea came from a friend. Early in 2020, I mentioned that I’d walked 1,929 miles in 2019, and he suggested that maybe I could walk 2,020 miles in 2020. Adding just under 100 miles, which is less than 2 miles a week, certainly seemed well within my capacity. I sold my car in 2018 and have many reasons to go for a walk. However, I didn’t manage 2,020 miles in 2020, and I couldn’t increase my mileage significantly in subsequent years either, until now. As of this writing (December 14), I’ve walked 2,079 miles. I passed my target a week ago, on a Saturday morning when I walked a couple of loops in my neighborhood to catch some rare December sun and get my day off to a good start.

∞

The years of thinking about my goal but not achieving it had clarified for me the seasonal patterns in my walking: I tend to walk less in summer, when the heat makes it uncomfortable to be outside, and sometimes less in winter if it’s icy or extremely cold. I walk less when I’m held immobile by depression. I usually feel better when I walk, but sometimes I get so far down that it’s hard to leave the house. That’s part of what happened to me in 2020.

In 2020–2023, I noticed that I kept on track toward a number of miles that matched the year fairly well up until about May. After that, I slowly got so far behind that it became impossible to catch up. This year, I thought I’d keep a spreadsheet so that I’d be more aware of how I was doing. I set up one that showed my running total, by week and by month, and how far off I was from my target for each week and month in the year. Read more »

Water flowing over rocks in the river Eisack in Franzensfeste, South Tyrol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Rachel Robison-Greene

I’ll never forget the moment when it dawned on me that I had arrived at middle age. I caught a glimpse of myself in the mirror. Nothing much had changed—my eyes were the same distance apart. My nose was in the same place. My grey hairs were still mostly hidden in my ample mane. What was suddenly different was how I interpreted my self.

I poured through my selfies on my iPhone with the intensity of Narcissus gazing at his image in a pool. Had I, just now, interpreted myself correctly for the first time in years? Had I somehow misunderstood myself until now in ways I should have found humiliating? Who is my “self” and who gets to determine who has it right?

It’s common to convey this general line of inquiry as a set of persistence questions. What is it, if it is anything at all, that allows a thing or a person to remain the same thing or person through time and change? Is a ship the same if its planks are replaced and what has become of the marble when it is carved into a statue—that kind of stuff. Less abstractly but more painfully, it is an existential question: how can I keep my grasp on sanity when the locus of my frame of reference and the source of my motivation shifts like sand? In youth, our sense of self is awkward and underdeveloped but also vibrant and life affirming. Part of the difficulty of aging is the recognition that the self is mortal, contingent, and unstable.

Consider popular expressions involving the self: “I wasn’t myself today,” “Control yourself,” “Keep it to yourself,” “know yourself.” These expressions don’t exhort us to be sure to persist through time and change; they press us to be cognizant of something else, something more fundamentally personal. Our selves matter to us in a way that they don’t—and can’t—matter to rocks, plants, or snails. Doorknobs aren’t concerned with whether the version of themselves they’re projecting to others is one with which they will be comfortable when they go to bed at night.

Philosopher and neuroscientist Patricia Churchland argues that developing a sense of self was evolutionarily advantageous for humans. A creature that could recognize itself could understand itself as having a welfare—things could go well or poorly for it from its own point of view. Read more »

by Steve Szilagyi

The Naked Gun trilogy was a series of three film comedies released between 1988 and 1994. They were directed by David Zucker, who founded a new school of parody with his breakthrough movie, Airplane! (1980). Part of Zucker’s genius was casting grim-visaged actors from serious films and letting them loose in a perfectly silly universe. Leslie Nielsen, Lloyd Bridges, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar—he made some brilliant casting choices. He also made one grotesque error: O.J. Simpson.

Long ago, I interviewed Simpson for a publicity job and came away thinking that he was the greatest guy in the world. When the Naked Gun films came out, I laughed my head off. Simpson was in all three of them. He wasn’t much of an actor, but I thought he was a great sport to let Zucker use him as a slapstick stooge—just what I would expect from a super guy like Simpson.

Then came the murders of Nicole Brown and Ronald Goldman. After learning the details of that crime, I could never watch a Naked Gun film again. How could I? How could anyone laugh freely at a film that has the face of an atrocious killer in every shot?

Confronting Convergence. Something like this happened to me on a recent visit to the Buffalo AKG Art Museum. Among the masterpieces in the museum’s collection is Jackson Pollock’s Convergence (1952), one of his classic drip paintings. My usual practice (and probably yours) when viewing a Pollock is to stand back for a few minutes to take it all in, then move in close and mentally merge with Pollock’s universe of speckles and swirls.

This is what I started to do with Convergence. But I couldn’t take that last step. Something was blocking me, and I knew exactly what it was: my recent reading of historian Henry Adams’ book Tom and Jack: The Intertwined Lives of Thomas Hart Benton and Jackson Pollock.

Adams’ book is a splendid dual biography, full of insights and revelations. What came back to me, however, as I stood in the Buffalo museum, was Adams’ account of August 11, 1956, the last day of Pollock’s life, and the painter’s role in the death of an innocent young woman. Read more »

by David J. Lobina

And by ‘them’, I mean, of course, the rich!

I think it is fair to say that such a rallying cry has always resonated with certain people, and perhaps even more so now in the US, with a forthcoming Trump 2 administration seemingly to be filled with billionaires. And I’m sure there is a perfectly reasonable argument in favour of stripping rich people of most of their wealth and assets in one way or another, Marxist or otherwise. A Marxist argument, you say? Is there such a thing?[i]

One such argument would have to say something about the distribution of income in society, either under some form of socialism – to all according to their work – or under some form of communism – to all according to their needs – as Marx argued in the Critique of the Gotha Programme (roughly, of course…); but, in any case, there would be little justification for anyone to be very rich under either society.[ii]

A more interesting argument, which I borrow from one Robert Paul Wolff (link below), has it that in modern capitalism there is a divorce between the legal ownership of large corporations and the de facto day-to-day running of the business. That is, in joint-stock limited liability companies, ownership is widely dispersed in the form of shares of stock, and as a result the managers and directors that run the company operate in a state of relative isolation, with the further result, and this is key, that the Board of Directors (and the like) are rather free to set what dividends and compensation are due. And this in turn results

in a regular, systematic, unquestioned process of theft, [as] a portion of the profits is directed away from the shareholders who are the owners of the corporation and into the pockets of the managers, who are paid vastly more than the going rate for managerial labor [sic].

Or to quote one of the greatest lines in political philosophy:

The simple fact remains that capitalism is a system of economic organization that regularly, quietly, unremarkably transfers a portion of the annual collective social product into the hands of a small segment of the society who have come to own the means of production. As each year goes by, the owners of capital expand their ownership and thereby reinforce their control of the workers whose labor [sic] creates what they take as profit.

Exploitation, in other words, though in modern capitalism such exploitation is relative, by which I mean, following an influential paper, that the modern accumulation process tends to obliterate social distinctions among workers, thereby producing an internal labour segmentation process – a fragmented workforce, that is – and with it unequal rates of exploitation but higher profits for the capitalist. Read more »

by Adele A Wilby

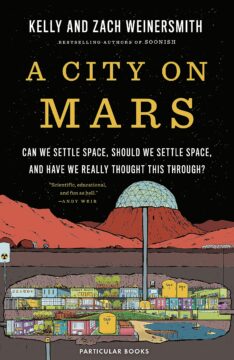

The images of a space shuttle lift-off and its propulsion into dark space with its astronauts strapped in, is an awesome site. Likewise, programmes such as Professor Brian Cox’s BBC series ‘Solar System’ that explores the Earth’s planetary neighbours for any signs of life and the potential for human habitability have a similar impact. But my interest in such events and programmes stems not from any idea I might entertain about a future in which human beings in their numbers will one day board space flights and head off to human settlements on Mars or the Moon or any other place that might support human life. Instead, it is the science that has enabled such developments, and the new knowledge to be gained from space exploration I find fascinating and exciting. I am not oblivious to the environmental crisis that the Earth is struggling with and the idea that space settlement might one day be the only alternative to the survival of our species, nor do I view it as a possible escape from the human condition and an opportunity for homo sapiens to have another shot at creating a better world for human existence, nor am I devoid of the spirit of adventure or curiosity that is reputed to characterise being human.

Fundamentally however, my lack of enthusiasm concerning off planet human settlements arises from a real appreciation of life in all its forms on Earth and a preference to deal with the immediate and urgent phenomenal existential issues that humanity confronts daily and, to use a well-worn cliché, make the world a better place for all here, and preferably now. Nevertheless, I am far from averse to learning about the issues involved in space settlements and Kelly and Zach Weinersmiths’ book A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have we Really thought this Through? provided me with an opportunity to do just that.

The husband-and-wife team, the Weinersmiths, won the 2024 Royal Society Trivedi Science Book Prize with this book, The City of Mars from amongst some stiff competition which included the 2009 Nobel Prize Winner for Chemistry, molecular biologist Venki Ramakrishnan’s Why We Die: The New Science of Ageing and the Quest for Immortality, a must go to book for those interested in the subject. And in a new and refreshing theme on biological sex differences, Cat Bohannon’s Eve: How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution, provides us with a comprehensible exposition of the science behind the development of the female sex and its contribution to evolution. To be chosen the winner of the 2024 Science Book Prize from amongst those two brilliant books alone suggests that the Weinersmiths’ book must have something special to offer, and it does. Read more »

Lorraine O’Grady. Art Is … , Float in the African-American Day Parade, Harlem, September 1983.

Lorraine O’Grady. Art Is … , Float in the African-American Day Parade, Harlem, September 1983.

“Over the course of more than three decades, artist and cultural critic Lorraine O’Grady has won acclaim for her installations, performances and texts addressing the subjects of diaspora, hybridity and Black female subjectivity. Born in Boston in 1934 and trained at Wellesley College and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop as an economist, literary critic and fiction writer, O’Grady had careers as a U.S. government intelligence analyst, a translator and a rock music critic before turning her attention to the art world in 1980.

In her landmark performance Art Is…, O’Grady entered her own float in the September 1983 African-American Day Parade, riding up Harlem’s Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard (Seventh Avenue) with fifteen collaborators dressed in white. Displayed on top of the float was an enormous, ornate gilded frame, while the words “Art Is…” were emblazoned on the float’s decorative skirt. At various points along the route, O’Grady and her collaborators jumped off the float and held up empty, gilded picture frames, inviting people to pose in them. The joyful responses turned parade onlookers into participants, affirmed the readiness of Harlem’s residents to see themselves as works of art, and created an irreplaceable record of the people and places of Harlem some thirty years ago. These color slides were taken by various people who witnessed the performance, and were later collected by O’Grady to compose the series. The forty images on view capture the energy and spirit of the original performance.”

From the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Richard Farr

I’m sixteen and a serious intellectual wannabe. Any lunch break, you can find me in the school corridors discoursing at length on a well-thumbed Hermann Hesse novel, or sharing with some lucky classmate the insights I’ve gleaned from half a dozen pages of Sartre. I’ve also acquired a taste for Gauloises Disque Bleu, wear my scarves just so, and plan to read Being and Nothingness one day. Though in truth I prefer Camus to Sartre — so much more dashing, so much more chic. It’s him I dream of being mistaken for as soon as I can get the right overcoat.

Economics is taught by Mr. W, an eccentric man it’s easy to make fun of and one of the best teachers I’ll ever have. He has assigned an essay on the “Mishan-Beckerman debate.” (Beckerman thinks unrestrained economic growth is good because it creates stuff; Mishan thinks it’s bad because it destroys stuff.) Because I’m an incipient leftie — inevitably, given my plan to study philosophy while living in a garret on the Rive Gauche — I think it obvious that there is really no debate to be had. A cursory reading shows that Mishan is merely articulating conclusions sensible people like me have already come to; Beckerman doesn’t know his arse from his elbow.

Generally speaking I’m a not-bad student, accustomed to getting an A or an A- even from Mr. W, who is a notoriously hard grader. He’s also notorious for his habit of handing our essays back, with quiet but acid commentary, in front of the whole class: “Cooper: messy as always — your handwriting looks like something produced at high speed on horseback — but intellectually acceptable. Collins: messy in every way; I do recommend having a stab at answering the question at some point during the exercise. Davis: the first three pages are pointless blather that should have been omitted, but bravo for arriving in roughly the right neighborhood during the last couple of paragraphs. Dixon: ah, what a breath of fresh air; simplicity and clarity and excellence; well done. Farr: a lackadaisical effort but I confess grudgingly that most of the essentials are correct. Fisher, oh Fisher: …” (dramatic pause; paper held up with thumb and forefinger like a dead mouse; an almost imperceptible shake of the head as it is dropped onto the offending author’s desk) “no.”

But he returns the Mishan-Beckermann essay privately — perhaps, I think afterwards, entirely to save my blushes. There is a table at the back of the classroom with a distracting view of the games fields. We sit on opposite sides and he slides my oeuvre across to me. A large red F sits in a circle in the top right hand corner near the title. His expression is intense, hawkish: irritation, or pity? Read more »

by John Allen Paulos

When studying a technical field there is a strong temptation, especially among those without a scientific background, to apply its findings in areas where they may not make sense or are merely metaphors. (“Merely” is perhaps unnecessarily dismissive since much of our understanding of these fields is metaphorical.) Quantum mechanics and Godel’s theorems are often used (or abused) in this way. Precipitous changes are deemed “quantum jumps” or unusual statements are proclaimed “undecidable.” Not even set theory is immune. I once heard a commentator refer to some curtailment of the first amendment as being inconsistent with the mathematical axiom of choice. Having mocked these pseudoscientific references, I nevertheless, and with a bit of trepidation, would like to briefly explore a metaphorical aspect of chaos theory.

Chaos theory, roughly speaking, studies complex systems of one sort or another whose state or condition changes or evolves over time and are hence termed dynamical systems. The underlying equations or laws describing them are deterministic, but they often give rise to systems very sensitive to initial conditions. (Tiny variations cascading into huge differences.) The systems are also nonlinear, which means that the effects of changes are not directly proportional to their causes. And, trumpets sound here, an astonishing property of nonlinear dynamical systems is that they can exhibit quite unpredictable behaviors that might appear might random, even though subject to deterministic laws.

What might such systems tell us not only about weather systems or economic systems, but also about our own inability to predict or make sense of things? An obstacle to predictability is the utter complexity of the associations and linkages in the world and ultimately in our brain. They can be chaotic in both the everyday sense and in the mathematical sense, the description of which I’ll spare you. Regarding the latter sense, the so-called Horseshoe procedure devised by topologist Steve Smale to illustrate the evolution of systems from regularity to mathematical chaos, is most suggestive. Such procedures or mappings are, in fact, a distinguishing feature of chaos.

To understand the procedure, imagine a cubical piece of white clay with a very thin layer of bright red dye running through the middle of it and forming a sort of red dye sandwich. Read more »

“This is conclusive, and if men are capable of any truth, this is it.”

…………………………………………………. —Blaise Pascal, on his wager

Blaise’s place is on a sunset strip

paved razor-straight through desert air

many cul de sacs veer from its hot black path

squeezed in a pass between mountains there,

west, where the day goes down in a blaze

The road’s white line on the northern side

is lit with votive flame-tipped wax

while, southside, glass-tubed neon glows

glazing away in pink-lit veneer

as fountains spit casino-high

from cool pools and golden taps

The landscape reeks of myrrh & beer

on a highway set with brilliant traps:

a bet to which Blaise alludes,

but away from which

Blaise-skeptics steer

A crooner sings from a glittery stage

with background bells of dollar slots,

a mix in warp & weft on a nameless loom

with Gregorian chants wrung

into gambler’s knots

—priests & players in cassocks, albs,

sequined shirts, and denim pants

—Sketchers shuffling under slick, chic suits,

heads with miter-lids and baseball caps

—water & booze from an aspergillum

dipped in Byzantine plastic flask and flung,

dots ears and eyes and throbbing sternums

beating for life in which wisdom basks

But, as if in Solomon’s chair,

Blaise calls all bettors there,

throws loaded dice against a wall

that runs from floor

past stratosphere,

past moon, past sun,

past galaxies through warps of space

to end of time, but

always ends down here

where gamblers grumble

and losers grouse

that the odds (by grace)

are always with the house

by Jim Culleny, 1/29/17

JIm Culleny – Blaises Place – Clyp

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Malcolm Murray

The world does not lend itself well to steady states. Rather, there is always a constant balancing act between opposing forces. We see this now play out forcefully in AI.

The world does not lend itself well to steady states. Rather, there is always a constant balancing act between opposing forces. We see this now play out forcefully in AI.

To take a step back, the balancing act is present whether we look at the micro or the macro level. On the micro level, in our personal lives, we have seen how almost everything is good in moderation, but excess of anything can be fatal. When it comes to countries’ economic system, history has provided enough examples for us to be fairly certain that capitalism leads to prosperity and communism leads to stagnation. However, we have also seen how unconstrained capitalism leads to a race to the lowest common denominator and can lead to decrease in quality of life on non-GDP measures for the majority of people. When it comes to political system, we can admire China in the short term, in awe of how autocracies get more things done than democracies, but we have also seen how unchecked power inevitably leads to human rights degradations for the majority of people.

It is the same at the meso level, with new technologies. The two big technology trends of the 2010s followed this pattern. Social media started out being a force for freedom, overturning dictators and connecting old friends, but left unchecked and unregulated, it deteriorated into a click-baiting attention maximizer, driving children to suicide. The gig economy started as an environmentalist utopia, with “collaborative consumption” of idle resources, but quickly deteriorated into the creation of a new proletariat, living on below-subsistence earnings.

So it is no surprise that we now face the same challenge with AI. As a society, we need to balance the opportunities with the risks. We need some AI regulation, but at the same time, not too much so that it stifles innovation. We know that AI offers the promise of tremendous upside as well as downside. On the upside, we have seen recent examples such as the release of the new GenCast AI model from Google DeepMind for weather prediction. This could help foresee extreme weather events better than existing models, saving lives in the process. But on the flipside, we keep seeing examples of AI used indiscriminately leading to severely negative outcomes. The recent shooting of the UnitedHealthcare CEO seems to have been partly motivated by AI-driven processes, and Amazon recently reported a huge uptick in cyber threats due to AI.

The tricky part is that the needle is always moving. At any given point in time, we may be either under-controlling or over-controlling a given risk. This means either letting AI developers and deployers run rampant with the risks, or drowning them in red tape. Either allowing for too many adverse outcomes in society, or conversely, depriving society of large potential benefits. Read more »