by Rafaël Newman

An empire, threatened on its flank, vents spleen

An empire, threatened on its flank, vents spleen

Upon the would-be sovereign state between

Its borders and a surly host beyond—

Which wavers not with weapons to respond;

The fray’s then joined by nations treaty bound

To emperors (one more, one less self-crowned):

And thus the world comes closer to a war

That will destroy both empires, and much more!

Now, do you think I mean our present plane,

Where Russia, versus NATO in Ukraine,

Once freed of its remaining moral shackle,

May trigger yet our terminal debacle?

Mistaken. I recall instead a time

Long past: which does, however, with ours rhyme.

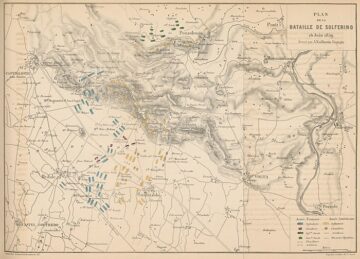

It’s 1859 and Lombardy,

To Habsburg lately sworn in fealty,

Raring Risorgiment-ally to rise

Italian and autonomous, allies

Itself with Piedmont and Cavour, il Conte—

And with Napoleon the Third (less jaunty

Than the First, though uncle and his nephew both

To none but to themselves will pledge their troth).

These grandees fling their gauntlets at the feet

Of Francis Joseph, on whose balance sheet

The loss of Lombardy were scarce redressed

By assets in Galizien, or Budapest;

And who is thus obliged to quit his court

For Solferino, where the kingly sport

Of war awaits him, and his regents rival,

To prove which prince is worthy of survival.

But here’s the place where parallels part ways

And leave us to our later, lesser days.

For though the Kremlin calques the Kaiser and

The Pentagon’s as potent, if no wiser than

L. Bonaparte, while Brussels is the farce

To V.E.R.D.I.’s tragedy: yet try to parse

The rest—the battle proper, where each chief

Championed in person his own proper fief;

The last engagement on this bloody ball

Whose each host heeded its own monarch’s call

To arms; a skirmish where the issue was decided

In combat riskily by mounted royals guided—

And you’ll agree our progress technological

Comes at the cost of glory demagogical.

For where’s the majesty in leading men

By proxy into war, and out again?

What is a Situation Room compared

With Solferino, where Franz Joseph dared

To meet head on Victor Emmanuel

And Bonaparte—although it sound the knell,

If distant, for his coupling Kaisers’ clan

And for their Holy Roman Bantustans?

Where are such doughty captains in our day,

Who blanch not at the fracas and the fray

But swing their booted form upon a steed

And with a battle-cry their soldiers lead?

Or better yet—for valor in a crowd

Nor shines as bright, nor halloos half as loud

As on its own—let’s send our current masters

In single combat off to their disasters:

Let Vladimir Vladimirovich meet

Mark Rutte in a dead and final heat—

The latter, if he likes, with von der Leyen

For balance, and for bank, and local buy-in;

As for the former, should he need a boon

Companion, he can cozen Kim Jong Un.

Let Netanyahu call out Khamenei

(With Assad seconding, by Zoom relay);

Let Trump lead Xi and Trudeau, Musk and Vance

A merry MAGA trade-war Totentanz…

But give them, like Montcalm and Wolfe, the grace

To expunge each other from the human race

(Or Polynices and Eteocles:

Plus we would grant a grave to both of these)…

And leave their peoples, quondam cannon fodder,

To enjoy the mêlée as intact applauders.

Or simply: to ignore the spectacle,

And sport themselves instead in dialectical

Disputes, in theater and thaumaturgy:

Nor any sort that calls for cross and clergy,

But rather wonders of the worldly kind,

Which calm the body and excite the mind;

Avoid all mongering, of hate or war—

Just maybe fish, to please the carnivore.

Leave them, who’ve borne their admirals’ abuses,

To guidance rather by nine gracious Muses;

Let them be spared the dreadful death-bound draft,

And turn their hand instead to vital craft.

And thus my prayer: deliver us, dear readers,

Out of the hands of all these bloody leaders!

_______________________________

In memory of journalists and media workers killed in Gaza

Some people use religion to get their life together. Good for them. I’m all for it. Although I myself am an atheist, I don’t think it much matters how someone gets their life together so long as they do.

Some people use religion to get their life together. Good for them. I’m all for it. Although I myself am an atheist, I don’t think it much matters how someone gets their life together so long as they do.

On the one hand, nothing has changed since August 2020, when I wrote

On the one hand, nothing has changed since August 2020, when I wrote

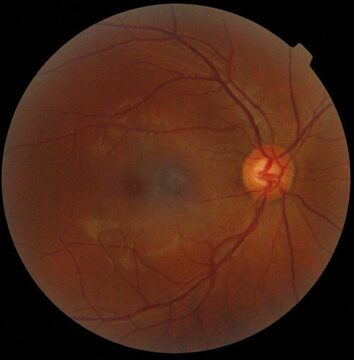

Anatomically, it’s the optic disc – the spot on each retina where neurons with news from all the light-sensitive rods and cones of the retina converge into the optic nerves. The optic disc itself,

Anatomically, it’s the optic disc – the spot on each retina where neurons with news from all the light-sensitive rods and cones of the retina converge into the optic nerves. The optic disc itself,

Sughra Raza. Rorschach Landscape, Guilin, China, January 2020.

Sughra Raza. Rorschach Landscape, Guilin, China, January 2020.

Of course there was no guarantee that Gerver’s couch was the biggest possible. Dr. Gerver’s approach made no promises that it gave the best possible, after all. A little more convincing is the fact that in 30 years we haven’t been able to do any better. But mathematics is a game of centuries and millennia — a few decades is small potatoes. In 2018, Yoav Kallus and Dan Romik proved that the couch could be no larger than 2.37 square meters. But the gap in size between Gerver’s couch and the Kallus-Romik upper bound is an order of magnitude larger than that between the couches of Gerver and Hammersley.

Of course there was no guarantee that Gerver’s couch was the biggest possible. Dr. Gerver’s approach made no promises that it gave the best possible, after all. A little more convincing is the fact that in 30 years we haven’t been able to do any better. But mathematics is a game of centuries and millennia — a few decades is small potatoes. In 2018, Yoav Kallus and Dan Romik proved that the couch could be no larger than 2.37 square meters. But the gap in size between Gerver’s couch and the Kallus-Romik upper bound is an order of magnitude larger than that between the couches of Gerver and Hammersley.

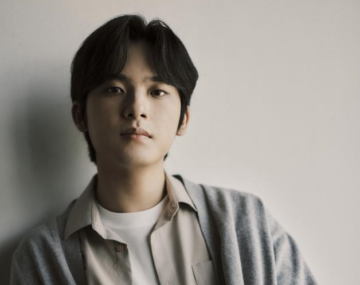

Someone else who understands the power of a single note is pianist Yunchan Lim, winner of the 2022 Van Cliburn competition at age 18, who electrified the classical music community with his performances of Rachmaninoff’s Concerto No. 3 and Liszt’s Transcendental Études and has since sold out concerts around the world. His reputation for virtuoso barrages of perfect notes at dizzying speeds belies a deep engagement in the sound he can extract from the piano with a single note—a process he demonstrated in

Someone else who understands the power of a single note is pianist Yunchan Lim, winner of the 2022 Van Cliburn competition at age 18, who electrified the classical music community with his performances of Rachmaninoff’s Concerto No. 3 and Liszt’s Transcendental Études and has since sold out concerts around the world. His reputation for virtuoso barrages of perfect notes at dizzying speeds belies a deep engagement in the sound he can extract from the piano with a single note—a process he demonstrated in