by Dick Edelstein

Catalan jazzman Ignasi Terraza and his trio lit up Barcelona with eight sets in October at Jamboree, a cutting edge Gothic Quarter club in the neoclassically-styled Plaça Reial, once an historic crossroads of the Camino de Santiago with the Roman Via Augusta, now a nexus of Barcelona night life and the local jazz scene. The series marks the 25th anniversary of the first Jazz a les Fosques concert that the blind pianist performed in darkness, letting listeners share his sensory experience and gain insight into his musical sensibility.

Anyone who can walk in someone else’s shoes is either a saint or a specially sensitive individual, so when Terraza joked that being sighted is overrated, the audience caught the irony, insanely proud of his accomplishment as the leading exponent of Catalan jazz. His compatriot Tete Montoliu once burnished Catalunya’s image, like cellist-composer Pau Casals, whose Cant dels ocells is broadcast worldwide from Camp Nou football matches to mark a moment of silence for departed socis. Four decades ago in San Francisco, when I told a local jazz musician that I was moving to Barcelona, he replied “That’s in Catalunya—that’s where Tete Montoliu lives”.

In a darkened room, listeners tune in to the way a sightless pianist apprehends music synesthetically, as a cymbal crash becomes a circular pyrotechnic light-burst. Drummer Esteve Pi plays with a clarity that is melodic, architectural, economical, calibrated and precise, limning the structure of his discourse, not just in solos, also in ensemble parts. The trio’s limpid playing is framed by Swiss-Greek bassist Giorgos Antoniou’s supple bass lines and subtle styling; and on opening night, guest singer Laura Simó surprised listeners with a crystalline enunciation of English syllables that added an attractive twist to her interpretation of Billy Strayhorn’s romantic recitative ballad “Lush Life”, a jazz standard whose stock goes up with each new generation. Other nights, rising-star trumpet player Joan Mar Sauqué and Australian clarinet-flautist Adrian Cunningham created unexpected sounds with their instruments, formless textures that eventually resolved into structure. Read more »

I dipped my toe into

I dipped my toe into  Professor Paul Heyne practiced what he preached.

Professor Paul Heyne practiced what he preached.

by William Benzon

by William Benzon Last Saturday, November 2, 2024, at a collective atelier in Zurich’s Wiedikon neighborhood, I attended the launch of a new periodical.

Last Saturday, November 2, 2024, at a collective atelier in Zurich’s Wiedikon neighborhood, I attended the launch of a new periodical.

In 1919, Otto Neurath was on trial for high treason, for his role in the short-lived Munich soviet republic. One of the witnesses for the defense was the famous scholar Max Weber.

In 1919, Otto Neurath was on trial for high treason, for his role in the short-lived Munich soviet republic. One of the witnesses for the defense was the famous scholar Max Weber.

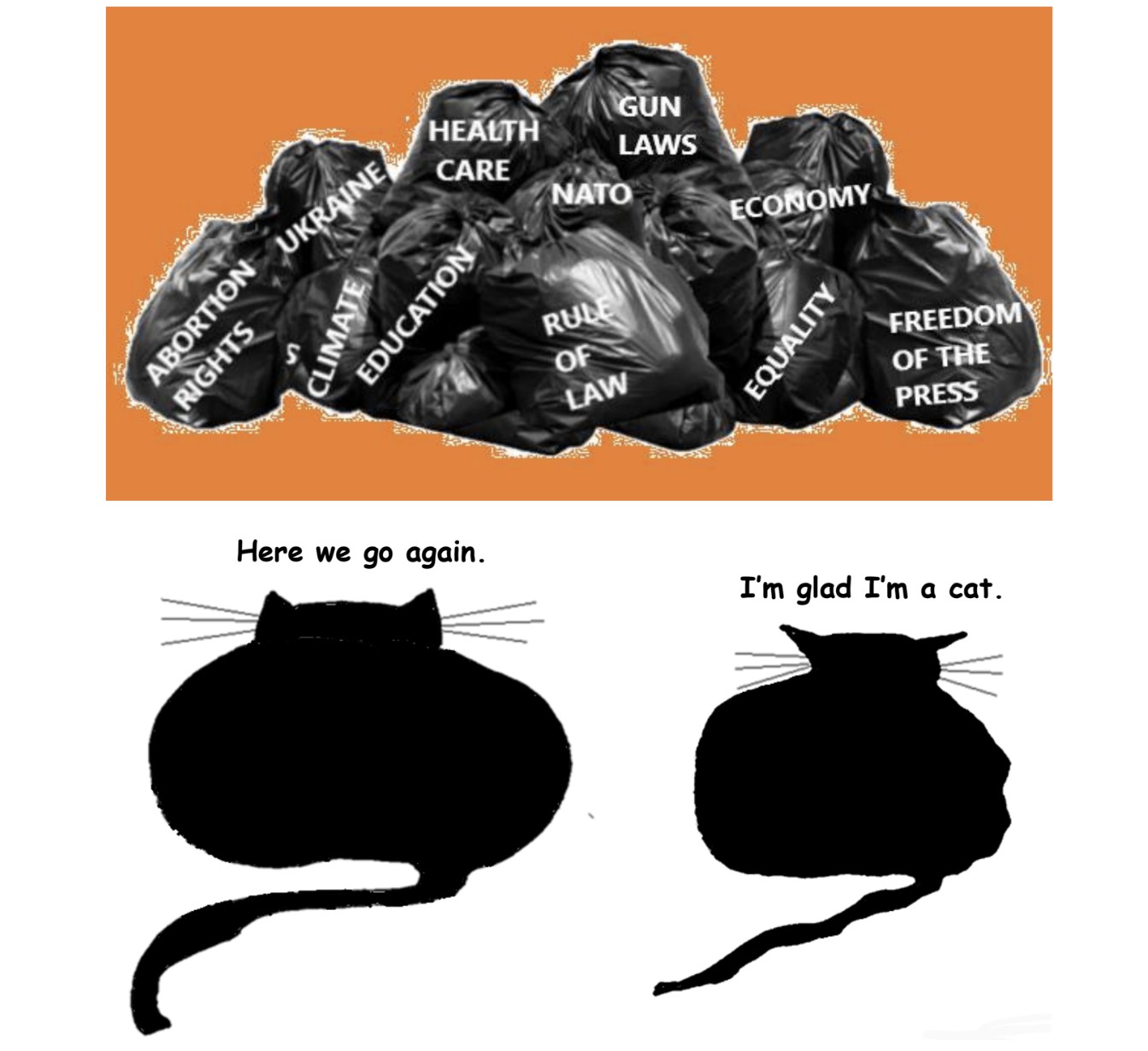

Historians have spilled much ink analyzing and interpreting all of the U.S. presidential elections, dating back to George Washington’s first go in 1788. But a handful of contests get more attention than others. Some elections, besides being important for all the usual reasons, also provide insights into their eras’ zeitgeist, and proved to be tremendously influential far beyond the four years they were intended to frame.

Historians have spilled much ink analyzing and interpreting all of the U.S. presidential elections, dating back to George Washington’s first go in 1788. But a handful of contests get more attention than others. Some elections, besides being important for all the usual reasons, also provide insights into their eras’ zeitgeist, and proved to be tremendously influential far beyond the four years they were intended to frame.

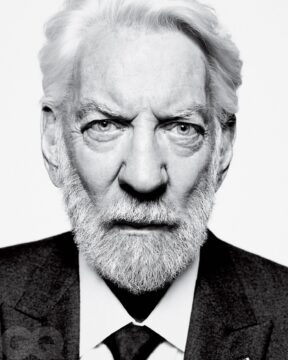

Donald Sutherland was a connoisseur of poetry. In the 80s I knew poetry-quoting doyennes from the glittering parties the Academy of American Poets threw as well as the Sudanese who recited their histories in song, but mostly I knew poets obsessed with competing with dead ones, with an eye toward their next book. Poets generally love poetry the way auto mechanics love cars. They don’t luxuriate in the front seat, or take long winding car trips through the Berkshires, they make sure the ignition catches and go on to the next one. Hearing Sutherland recite poetry you heard the Stanislavski method of poetry-recitation, an oral delivery straight from the mind as well as the mouth. Sutherland said he was manipulated by words, not as a ventriloquist but in the relationship between feeling and meaning. Likewise, after numerous tussles with directors Fellini and Preminger and Bertolucci – he even tried to get Robert Altman fired from M.A.S.H. – he decided he was merely the director’s vehicle. Poetry directed him.

Donald Sutherland was a connoisseur of poetry. In the 80s I knew poetry-quoting doyennes from the glittering parties the Academy of American Poets threw as well as the Sudanese who recited their histories in song, but mostly I knew poets obsessed with competing with dead ones, with an eye toward their next book. Poets generally love poetry the way auto mechanics love cars. They don’t luxuriate in the front seat, or take long winding car trips through the Berkshires, they make sure the ignition catches and go on to the next one. Hearing Sutherland recite poetry you heard the Stanislavski method of poetry-recitation, an oral delivery straight from the mind as well as the mouth. Sutherland said he was manipulated by words, not as a ventriloquist but in the relationship between feeling and meaning. Likewise, after numerous tussles with directors Fellini and Preminger and Bertolucci – he even tried to get Robert Altman fired from M.A.S.H. – he decided he was merely the director’s vehicle. Poetry directed him.