by Brooks Riley

1. Reality isn’t what it used to be. Neither is fiction.

Years ago, someone who worked for a daily soap opera production company told me that if a storyline included a wedding, the TV network and its stations would be inundated with wedding gifts for the fictional newlyweds—from fans unable to distinguish fact from fiction, reality from TV. Hard to believe.

But this is more or less what happened in 2016: A man who had played a successful boss on TV won the Presidential election. He wasn’t such a successful businessman, but he played one on TV. (He wasn’t really a president, but he played one in the White House.) Eight years on, that cosplayed success is still branded on the minds of Trump supporters. No facts, scandals, or criminal convictions can shake their faith in the tenacious fictions of a reality show.

With so much knowledge and information at our fingertips, why haven’t we gotten smarter? Even now, when we can see with our own eyes how it happened in 1933, we are still in danger of becoming history’s recidivists.

2. History on repeat

Hardly a day goes by without some comparison between the US election’s worst-case scenario and the end of the Weimar Republic in Germany. This is a classic trope, now feeding off a déjà vu of epic proportions as America faces the very real possibility of becoming a dictatorship. Given the far right’s easy violence and fascist thinking and Donald Trump’s menacing Hitler-friendly rhetoric, together with his threats against his opponents and against the rule of law, it’s a valid trope that won’t go away until Trump is defeated in November.

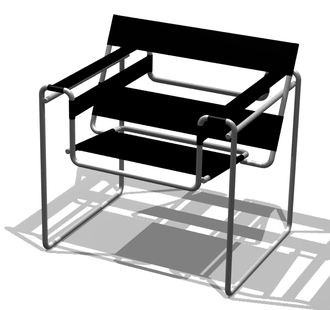

With the US election dominating the news, it may have gone unnoticed that the Bauhaus, the greatest architecture and design movement of the 20th century—sibling of that fabled Weimar Republic—is having a déjà vu moment of its own. Alternative für Deutschland, the far-right political party which made major gains in eastern Germany in recent elections, has attacked the Bauhaus, calling it ‘inhumane’ and an ‘aberration of modernity.’ In the state legislature of Saxony-Anhalt, the AfD motioned for a reduction of funds to the Bauhaus foundation in Dessau and warned against a ‘one-sided glorification’ of the Bauhaus during the 100th Anniversary celebrations next year. One politician called the famous Bauhaus School building in Dessau ‘of an abysmal ugliness’ and ‘unbearable to look at.’

As Stefan Trinks of the Frankfurter Allgemeine points out, the AfD’s language echoes that of Paul Schultze-Naumburg, the Nazi journalist who attacked the Bauhaus relentlessly from its inception in 1919 to its demise in 1933.

Reactions of outrage to the AfD motion were loud throughout Germany and the motion was defeated. But it was also clear to many, that the AfD uses such shock tactics to gain national attention. (Take note, America: One way Trump keeps your attention is to keep saying outrageous things.)

3. ‘It could never happen here!’

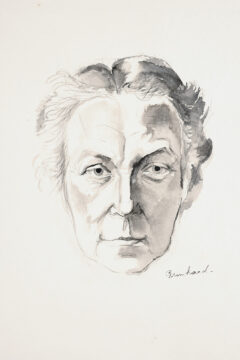

Coincidentally, the only person ever to warn me that ‘it could happen here’ was Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, architectural historian and widow of painter and Bauhaus professor László Moholy-Nagy. It was at an Architectural League event in New York in the late sixties—a time of student protests against the war in Vietnam and violent police crackdowns. I disagreed with her. I didn’t believe we could ever be awful enough to allow our country to become a fascist dictatorship.

Coincidentally, the only person ever to warn me that ‘it could happen here’ was Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, architectural historian and widow of painter and Bauhaus professor László Moholy-Nagy. It was at an Architectural League event in New York in the late sixties—a time of student protests against the war in Vietnam and violent police crackdowns. I disagreed with her. I didn’t believe we could ever be awful enough to allow our country to become a fascist dictatorship.

I was reminded of Mrs. Moholy-Nagy recently. I can still see her, an imposing figure, tall with an air of authority verging on arrogance. I think she saw me as a naïve young American, which I was. But looking back, I see my answer as arrogant too. I assumed the US would be too savvy to fall for the lure of a wannabe dictator.

As the election approaches, I still wonder how we’ve gotten this close to such a possibility. Germany was in desperate economic straits when people turned to the Nazis. America today is enjoying economic success. So why are people reaching out to an addled old man who promises to tear it all down?

4. Bauhaus and the Weimar Republic

The Bauhaus School and the Weimar Republic were both born in Weimar, Thuringia in 1919. While filming at the National Theater where that admirable but short-lived new democratic constitution was signed, I saw the plaque commemorating the event. It made me feel proud of the town, whose illustrious inhabitants have included Goethe, Schiller, Bach, Liszt, Nietzsche, Lucas Cranach the Elder, George Eliot, and many more. (But Weimar has a dark side too: The Buchenwald concentration camp is only eight miles away.)

As with the republic, all did not go well for the Bauhaus in Weimar. As the NSDAP grew stronger there after 1923, the city withdrew its financial support. The Bauhaus School was forced to move to Dessau, Saxony-Anhalt in 1925. A flurry of buildings followed, including the exquisite Walter Gropius-designed Master Houses where Paul Klee, Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky, Oskar Schlemmer, Gropius and Moholy-Nagy lived (with his first wife, the photographer Lucia Moholy). But the NSDAP was taking hold in Dessau too. The Bauhaus was ousted in 1931.

As fate would have it, work at the Anhaltisches Theater in Dessau gave me the opportunity to visit some of the iconic Bauhaus buildings. Seeing these architectural gems gleaming in a city that was still struggling to recover from two totalitarian regimes and a war in between, I felt hope for the future. I was sure that the Bauhaus oeuvre would always be Dessau’s cherished crown jewels—evidence of a time when looking ahead and moving forward had produced beauty, functionality, joy and the promise of a better life for everyone.

Today, with the world possibly headed in the opposite direction, I’m not sure of anything anymore.

For a deeper, more personal dive into the Bauhaus, here is my 3QD essay from 2019: My Bauhaus: A tale of two cities

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.