by Ben Orlin

There is something reassuring about teaching math. On the eve of a pivotal election, as my colleagues in U.S. history grapple with their subject’s urgent and terrible relevance, I can console myself that math is rarely urgent, and (as we tend to teach it) almost never relevant.

Or so it would seem. But math has a guilty secret: its longstanding role in American statecraft.

I’m not referring to math’s technocratic applications, or the pious calls for better STEM education. Rather, math has long inspired our country’s leaders for precisely the same reason that it befuddles our students: its willingness to wrangle with abstraction.

Math is the science of unifying laws. As such, it has served as a model for our messy republic’s perpetual efforts to live up to the “United” in its name.

I scarcely exaggerate when I say that we are the people of the equals sign.

Thomas Jefferson was an avid mathematician. He described calculus as “a delicious luxury,” and trigonometry as “most valuable to every man,” adding, “there is scarcely a day in which he will not resort to it.”

(Sidebar: I spent years teaching trig, and never once heard this sentiment echoed.)

In 1776, when Jefferson penned his famous equation—that all men are created equal—he was not trying to set the U.S. apart. Quite the opposite: the Declaration’s goal, he later wrote, was “to place before mankind the common sense of the subject,” so as to persuade other nations of our cause.

“All men are created equal” was intended as a banality, a truism. It was an obviously acceptable premise from which the argument could proceed. In his draft, Jefferson called this truth “sacred and undeniable.” Ben Franklin edited it to the more mathematical “self-evident.”

Either way, the purpose was to borrow, on behalf of uncertain times, the timelessness and certainty of mathematics.

Four score and seven years later, the phrase fell into the hands of our sixteenth and greatest president, Abraham Lincoln—who was, by no coincidence, an amateur mathematician himself. One time, years before his presidency, his law partner found him amid piles of crumped paper, attempting to square the circle.

Lincoln’s intellectual hero was the ancient geometer Euclid, whose built his towering arguments on bedrock assertions about the nature of equality. “It is a self-evident truth,” quotes the onscreen Lincoln in Spielberg’s 2012 film, “that things which are equal to the same thing are equal to each other.”

In real life, as in Tony Kushner’s screenplay, Lincoln found in Euclid a wisdom that was more than mathematical. “We begin with equality,” the onscreen Lincoln goes on. “That’s the origin, isn’t it?… That’s justice.”

Mathematics, in Lincoln’s eyes, offered a model for democratic statecraft. He makes this explicit in the Gettysburg address.

With arithmetical flair, Lincoln dates the U.S.’s birth not to the messy compromises of its governing Constitution (ratified three score and sixteen years prior) but to the soaring generalities of its Declaration (four score and seven years prior). In doing so, he puts a new spin on the idea of human equality.

Jefferson invoked equality as common sense. But in Gettysburg, Lincoln recast it as our highest civic aspiration. He imagined equality as a kind of Euclidean axiom, a foundational assumption from which all else follows: “a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

On the Civil War’s bloodiest battlefield, the U.S. is reborn in the model of Euclid, as a living consequence of an abstract truth.

Here I should lay my own cards on the table. I’ve written four books extolling the power of mathematical ideas. I’ve dedicated my career to the proposition that mathematics can enrich every life. Even so, I’m flabbergasted to hear politicians draw on math.

“Really?” I want to ask. “You—a practitioner of the nastiest, most necessary, most pragmatic line of work—you find useful meaning in mathematics?”

At its most brutal level, politics is a series of collisions over material interests. Taxes on tea and stamps; the benefits of marital status; the enslavement of labor; the redistributive impact of tariffs. Politics, for better and for worse, is about stuff.

Math is emphatically not about stuff. An equation as simple as 2+2=4 depends on our rejecting the natural question: Four of what? An equation is not about apples, humans, or planets. It is about all of these and none of them. Where is the political value in such abstractions?

Well, the abstraction is the value. Our leaders need to lift us above particulars, to awaken our sense of universals. Equations do that job beautifully.

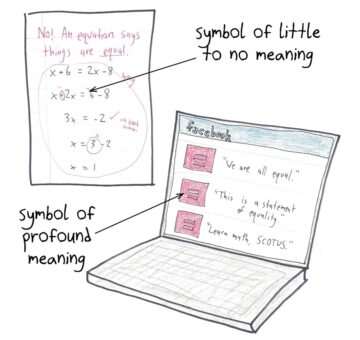

Perhaps that’s why, in 1995, the Human Rights Campaign adopted the equals sign as their logo, making it a ubiquitous symbol of LGBTQ rights. I remember the surreal spring of 2013, when millions of Facebook users donned that logo as their profile image, in a chorus of support for marriage equality.

By day, I hectored young people about the proper uses of the equals sign. Then, in the evenings, I scrolled through page after page of young people putting the equals sign to a use more profound than I could have imagined.

Alas, in a republic as contentious as ours, every principle has its detractors.

Even equality.

In 1948, the conservative Richard Weaver made a direct attack on equality, denouncing it as a historical Johnny-come-lately. You can’t unify a people on mere equality, he said. What we need is “fraternity,” an “ancient feeling” which “goes immeasurably deeper,” and “carries obligations of which equality knows nothing.”

I admit that Weaver has a case. Equality, like any abstraction, makes its appeal not to the heart, but the mind. A nation “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” is not, and never can be, a nation united by a fierce, tribal love of kin.

And that’s exactly the point. The U.S., in the eyes of its most visionary leaders, has always been a nation of principles, a nation of symbols.

A nation of abstractions.

“Abstract things aren’t necessarily less real to me than ‘real’ things,” mathematician Eugenia Cheng once wrote. “Tiredness is abstract but feels very real to me, whereas the bottom of the Pacific Ocean is real but feels very abstract.”

Watching this election unfold on social media, I have sometimes felt plunged onto the wrong side of Cheng’s dichotomy. The quotes, the clips, the maddening takes—they all feel terribly real. But what kind of real are they? These cherrypicked, repurposed, context-stripped fragments—why fill my mind with these things? They are, by and large, as meaningless as the Pacific seafloor. Better to turn to our national abstractions.

Like all mathematics, equality is a simplification. No two Americans are alike. No two are interchangeable. In a strict mathematical sense, we are not “equal,” but wonderfully (and maddeningly) individual.

Yet through our civic life, we are all created equal, and each election we dedicate ourselves to creating that equality anew.

***

Ben Orlin loves math and cannot draw. He is mostly known as “the math with bad drawings guy.” He has taught middle school, high school, and college math, spoken at conferences and universities across the U.S., and has written (as well as badly illustrated) four books: Math with Bad Drawings (2018), Change is the Only Constant (2019), Math Games with Bad Drawings (2022), and Math for English Majors (2024). He lives in Saint Paul, MN with his wife, their two daughters, and his inordinate fondness for sweets.

Ben Orlin loves math and cannot draw. He is mostly known as “the math with bad drawings guy.” He has taught middle school, high school, and college math, spoken at conferences and universities across the U.S., and has written (as well as badly illustrated) four books: Math with Bad Drawings (2018), Change is the Only Constant (2019), Math Games with Bad Drawings (2022), and Math for English Majors (2024). He lives in Saint Paul, MN with his wife, their two daughters, and his inordinate fondness for sweets.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.