by Mike O’Brien

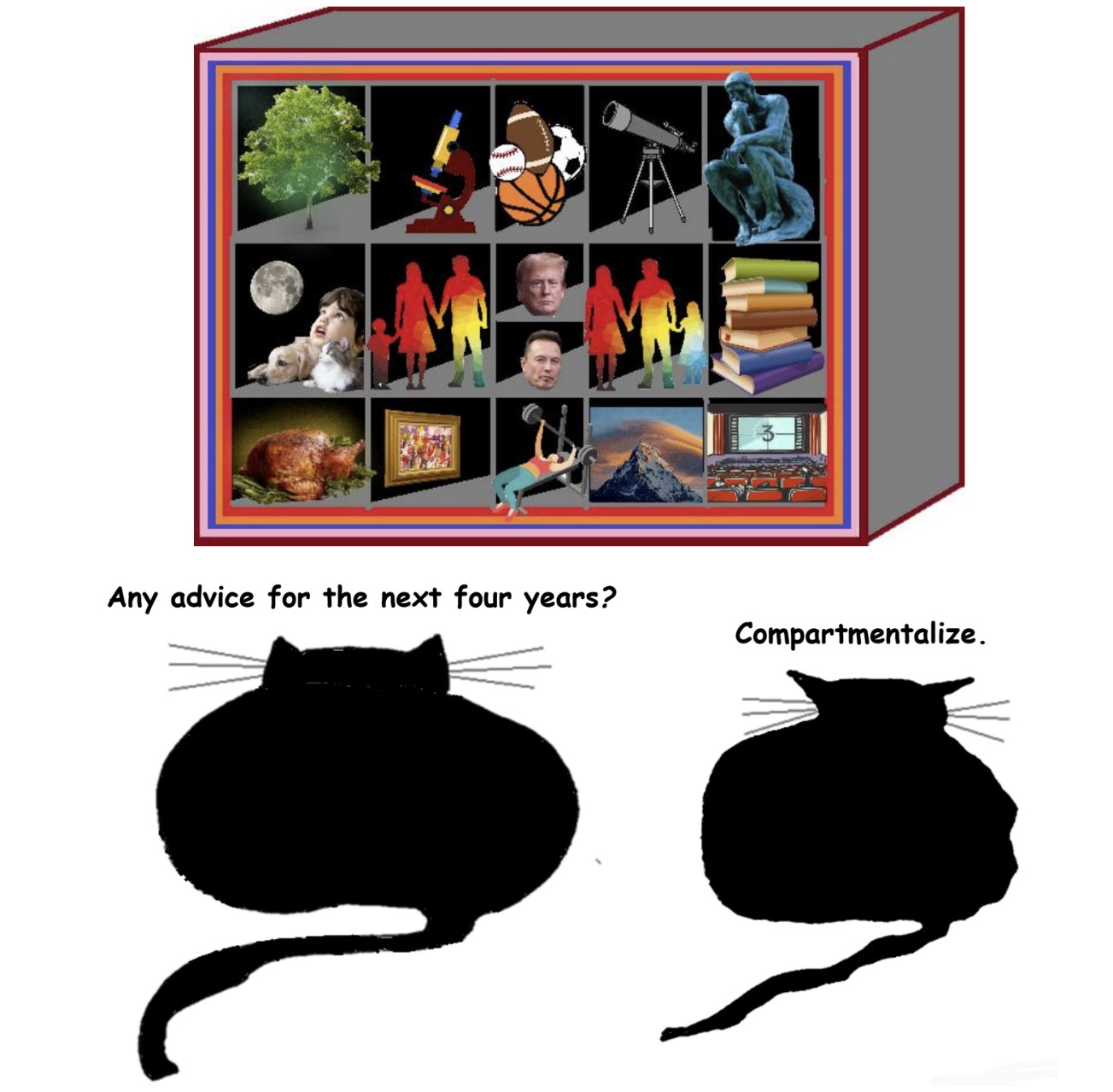

It has been a busy few months in the field of animal studies. It seems like every month is a busy one for animal studies these days, which is salutary. As a hobbyist follower of this area of study, every time I turn around there is a new line of research to catch up on. All the better for me, as it eats up reading time that might otherwise be spent doom-scrolling through the latest outrages and tragedies. Save me from myself, you heroes of scholarship.

The first item of note is the honouring of Lori Gruen as “Distinguished Philosopher of the Year” by the Eastern division of the Society for Women in Philosophy, an American organization that has been supporting and promoting women philosophers for over fifty years. Gruen is a prolific and influential figure in the ecofeminist tradition, focusing mainly on environmental and animal ethics as well as on the ethics of incarceration, and has published extensively over the last three decades. She has also been a mentor, collaborator and co-author with many other people in the field, and I have come across her work several times over the last few years while reading through other researchers’ bibliographies.

I haven’t read enough of her work or ecofeminist work generally to have a well-informed opinion of it, but my not-well-informed sense is that it leans towards normative ethics and elaborating the entailments of posited moral facts, which is outside of my preferred meta-ethical wicket. (Once the worm of Nietzschean critique gets into your brain, it becomes difficult to find any enthusiasm for the discovery or analytical definition of moral facts). I also have some general misgivings about the essentialist bent of much of the ecofeminist work that I’ve encountered (e.g. relational ethics is feminist, empiricist science is patriarchal), which has kept me from engaging with that literature more than incidentally. I nevertheless remain open to the possibility that these impressions are mistaken and, given that most of the targets of ecofeminist critique are certainly real and disastrously powerful, I am glad that they have their oars in the water, paddling in roughly the right direction. This is a common muddle in normative ethics, where some things are so obviously wrong (animal cruelty, systemic racism, environmental destruction) that a very wide swath of viewpoints can converge on a common conclusion despite profound disagreements about facts, values and methods.

Coincidentally, Gruen co-authored an entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (the Wikipedia of academic philosophy) on “The moral status of animals” with another animal philosopher who has been in the news of late. Susana Monsó, whom I have mentioned in earlier columns owing to her co-authorship with Kristin Andrews of several works, has been hitting the interview circuit to discuss her book “Playing Possum: How Animals Understand Death”, newly translated to English. The book explores the experience and understanding of death among non-human animals, using examples from wild and captive creatures to argue that many animals do in fact have a concept of death. Read more »

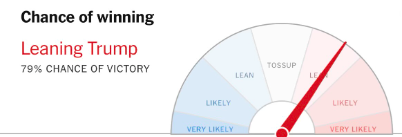

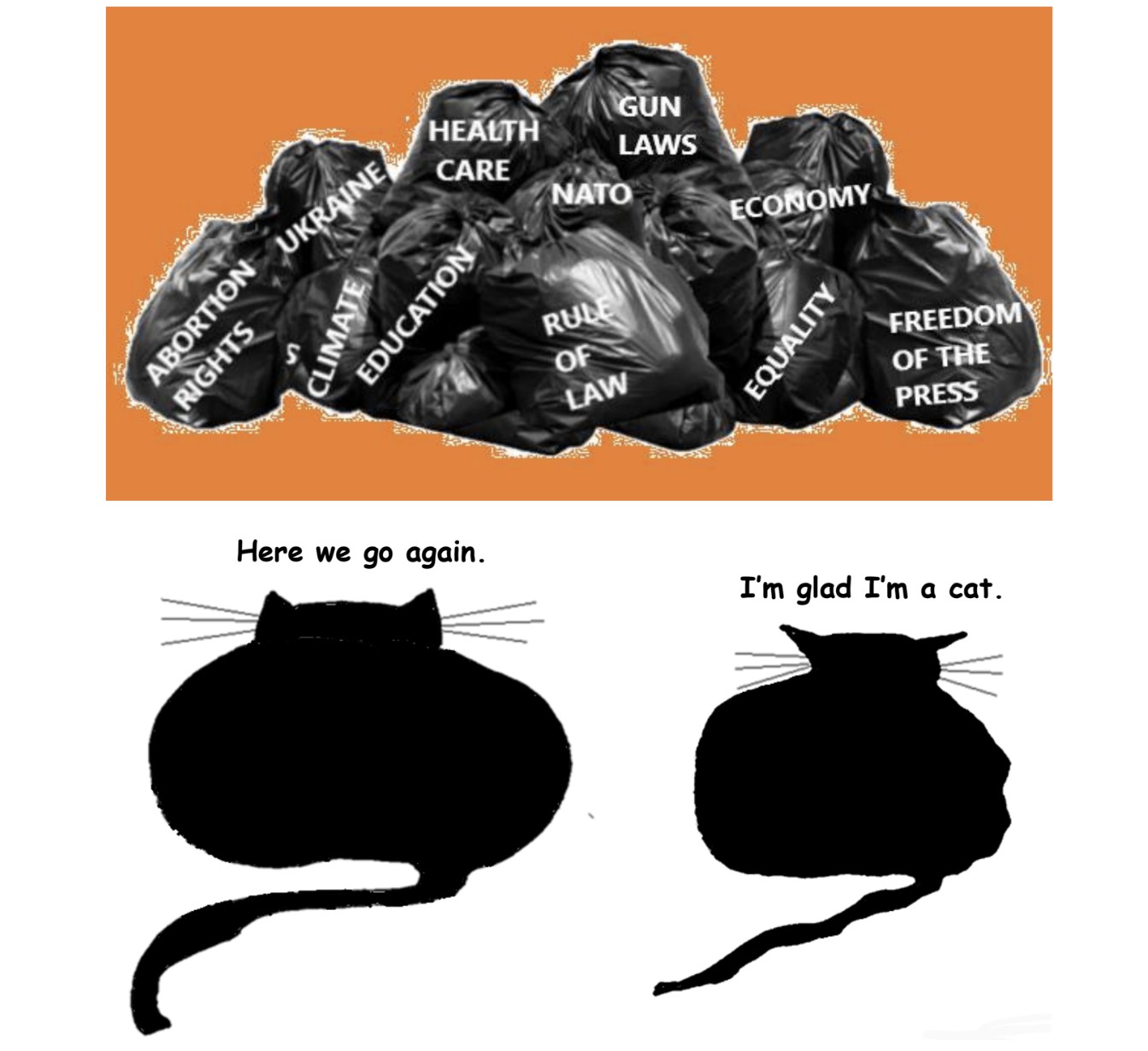

On November 5, 2024, at around 10:30 pm, I walked into a bar, approached the counter, and sat down on the stool second from the right. I ordered a stout because there was a slight chill in the air. As this was the night of the American presidential election, I pulled out my phone and checked The New York Times website, which said Donald Trump had an 80% chance of winning. This was my first update on the election, and it seemed bad. I put my phone back in my pocket and took a sip of the stout. A man entered the bar and sat down next to me, on my right. There was a half-drunk glass there, and I realized he’d gone out to smoke but had probably been at the bar for a while. Besides us—two solitary men at the bar—the rest of the place was busy, full of couples and groups who seemed to be unconcerned with the election. This may have been because I was in Canada, but my experience of living in Canada for the past four years has shown me that Canadians are just as interested in American politics as Americans are, if not more so. My work colleagues had been informing me of the key swing states, for example, while I had simply mailed in my meaningless Vermont vote and returned to my life. I had no idea who would win this election.

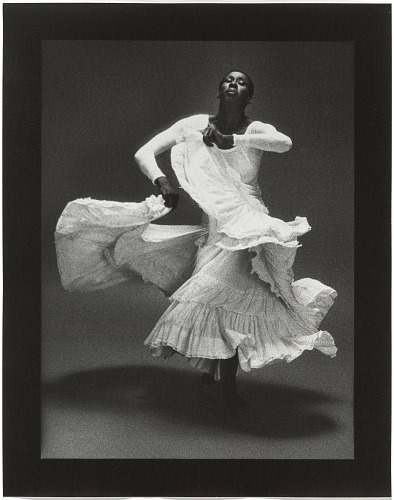

On November 5, 2024, at around 10:30 pm, I walked into a bar, approached the counter, and sat down on the stool second from the right. I ordered a stout because there was a slight chill in the air. As this was the night of the American presidential election, I pulled out my phone and checked The New York Times website, which said Donald Trump had an 80% chance of winning. This was my first update on the election, and it seemed bad. I put my phone back in my pocket and took a sip of the stout. A man entered the bar and sat down next to me, on my right. There was a half-drunk glass there, and I realized he’d gone out to smoke but had probably been at the bar for a while. Besides us—two solitary men at the bar—the rest of the place was busy, full of couples and groups who seemed to be unconcerned with the election. This may have been because I was in Canada, but my experience of living in Canada for the past four years has shown me that Canadians are just as interested in American politics as Americans are, if not more so. My work colleagues had been informing me of the key swing states, for example, while I had simply mailed in my meaningless Vermont vote and returned to my life. I had no idea who would win this election. Max Waldman. Judith Jamison in “Cry”, 1976.

Max Waldman. Judith Jamison in “Cry”, 1976.

What does the election of Trump mean for risks to society from advanced AI? Given the wide spectrum of risks from advanced AI, the answer will depend very much on which AI risks one is most concerned about.

What does the election of Trump mean for risks to society from advanced AI? Given the wide spectrum of risks from advanced AI, the answer will depend very much on which AI risks one is most concerned about.

I dipped my toe into

I dipped my toe into  Professor Paul Heyne practiced what he preached.

Professor Paul Heyne practiced what he preached.

by William Benzon

by William Benzon Last Saturday, November 2, 2024, at a collective atelier in Zurich’s Wiedikon neighborhood, I attended the launch of a new periodical.

Last Saturday, November 2, 2024, at a collective atelier in Zurich’s Wiedikon neighborhood, I attended the launch of a new periodical.

In 1919, Otto Neurath was on trial for high treason, for his role in the short-lived Munich soviet republic. One of the witnesses for the defense was the famous scholar Max Weber.

In 1919, Otto Neurath was on trial for high treason, for his role in the short-lived Munich soviet republic. One of the witnesses for the defense was the famous scholar Max Weber.

Historians have spilled much ink analyzing and interpreting all of the U.S. presidential elections, dating back to George Washington’s first go in 1788. But a handful of contests get more attention than others. Some elections, besides being important for all the usual reasons, also provide insights into their eras’ zeitgeist, and proved to be tremendously influential far beyond the four years they were intended to frame.

Historians have spilled much ink analyzing and interpreting all of the U.S. presidential elections, dating back to George Washington’s first go in 1788. But a handful of contests get more attention than others. Some elections, besides being important for all the usual reasons, also provide insights into their eras’ zeitgeist, and proved to be tremendously influential far beyond the four years they were intended to frame.