by Brooks Riley

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Jonathan Kujawa

Among our many flaws, humanity prefers to be shortsighted. We tend to set our priorities by what we see right in front of us. This makes some sense. After all, there is no point in worrying about storing food for the winter when facing down a saber toothed tiger. But eventually winter arrives.

There is a reason Aesop told us the fable of the Ant and the Grasshopper. Children want to stay up late, eat candy for every meal, and skip anything that seems like work. As we grow up, we hopefully learn the value of investing in our future.

But just planning for the next winter is not what got us to where we are today. Hobbes said the natural life of a human was “solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short”. We may still sometimes be nasty brutes to each other, but most of us have long lives filled with health, wealth, and ease.

The progress of the last century is astonishing. When my grandfather was a young boy, the Wright brothers flew at Kitty Hawk. When my parents were children, polio was a real worry [1]. When I was young, international phone calls were a dollar per minute, shopping options were limited to whatever the local stores carried, and the sum total of knowledge on a subject was contained in the encyclopedias at the library. Now we have transcontinental flights, a polio vaccine, and the internet.

How did we get from there to here? I can tell you what we didn’t do. We didn’t just solve today’s problems. We also invested in solving future problems, even problems we didn’t know existed. Even the times when we made a maximum effort to solve a hard problem of the day (the atomic bomb, the moon landing, the Covid-19 vaccine), we depended on the prior work of people who were interested in developing our fundamental knowledge with no immediate application in mind.

There will always be a tension between the problems of today and an investment in the future. We have pressing needs, and it can be hard to trust that research driven by curiosity is worth the cost. Especially when the research sounds nonsensical or when its utility is impossible to imagine. And it’s true that much of that research will never come to anything.

But when it pays off, it pays off big. Non-Euclidean Geometry was an idle amusement until it was key to understanding spacetime and, in turn, gave us space travel and GPS. The numerology of elliptic curves was an esoteric glass bead game until it became the ubiquitous key ingredient of modern cryptography. The theory of Linear Algebra was developed with no idea that it would be essential to Google Search and the current AI explosion. All of mathematics could be funded on a tiny sliver of the profits generated off of the discoveries of a century ago [2].

by Lei Wang

[This is part of a series on bringing magic to the everyday through imagination.]

Someone once told me the trick to fasting: take long walks. That way, your body believes you are at least on the search for food and temporarily forgets its hunger. When you’re in the mode of actually solving the problem, the problem tends to go away, as opposed to endless rumination about the problem. Then again, the person who told me this was the kind of person who could do things merely because she knew they were good for you. This was another one of those common sense yet counterintuitive things I often fail to put into practice, along the lines of how using energy somehow begets energy, while sleeping all day makes you sleepier.

I rarely fast, but I often find myself hungry and slightly irritated—I am one of those people—and wonder if I can take the trick a step further, using my imagination. Hunger already lends itself to animal metaphors—“I could eat an elephant,” “I’m a hungry hippo”—so why not take it all the way? On the sidewalk nearing noon, I become a large savannah cat chasing my wildebeest. At my desk, a squirrel savoring each nibble of a stolen cashew. Or a crocodile lying in wait by the marsh grass/microwave. I must, in fact, focus and stay still to get my lunch, and this calms me down. Hunger starts to feel less like a problem and more like a game. Bringing meaning to things: this is what humans do, isn’t it? And we can just make up the meanings.

Of course, one can also just have a granola bar. I’m not even concerned so much about true physiological hunger—this being a sphere of excess—but the psychological kind. I am interested in dealing with our evolutionary wants, our programmed desires, with creative and unpunishing ways to choose otherwise. In other words: how do we not act like dogs when it comes to the food instinct, even if (let’s face it) we probably all long for the life of a very good middle-class dog? Read more »

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait At Home. December 2024.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait At Home. December 2024.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Tim Sommers

John Austin was cursed with famous friends, among them Jeremy Bentham, Thomas Carlyle, James Mill and Mill’s son John Stuart, whom Austin tutored in the law. Cursed because, while they were all impressed by his intellect and predicted he would go far, he did not. His nervous and depressive disposition combined with his ill-health lead to his failure as a lawyer, an academic, and as a government official. In 1832, Austin wrote The Province of Jurisprudence Determined, which almost no one read and promptly went out of print. Almost thirty years after his death, his widow published a second edition. This time, everybody read it.

Austin is considered the first positivist. Positivism is so-called because the law, on this account, is a “posit.” That is, all law is human-made, separate from morality, and identifiable as law by the details of how it came about – and (most importantly) the fact that the source of law is habitually obeyed. Positivism aspires to be an empirical approach to the law. So, Austin says laws are rules, but, empirically, are also a species of command.

Specifically, a law is a command made to a subject, or political inferior, by a sovereign, or political superior, habitually obeyed, who can back the command up with a credible threat of punishment of sanction. No law without sanction. If I offer money to whomever finds my dog, even if I am the sovereign, it’s not a law.

There are problems with this approach. First of all, it seems to apply best to criminal law – and only with retrofitting to other kinds of law. As my Constitutional law professor, Paul Gowder, used to say, despite what people think, “The law does not, primarily, tell people what they can’t do. It tells them how to do what it is that they want to do. Get married. Open a business. Drive a car. Make a will.”

Secondly, in post-monarchial society, who exactly is the sovereign? Austin himself had difficulty. He was forced to describe the British “sovereign” of the time, awkwardly, as the combination of the King, the House of Lords, and all the electors of the House of Commons.

Finally, as Hart emphasized, it’s not clear, on this account, that we can make a principled distinction between the commands of the sovereign and the commands of a criminal with a gun. Read more »

by Ken MacVey

After many years as a practicing lawyer, I remain proud of what I do. Putting aside lawyer jokes, stale references to ambulance chasing and analogies with other professions that charge by the hour, I have enjoyed doing what lawyers do and I am unapologetic about it.

After many years as a practicing lawyer, I remain proud of what I do. Putting aside lawyer jokes, stale references to ambulance chasing and analogies with other professions that charge by the hour, I have enjoyed doing what lawyers do and I am unapologetic about it.

Sometimes to clients, colleagues, and classes that I teach, I give my elevator pitch on why law is essential to, in fact constitutive of American society. It varies but goes something like this –

“We are all aware of the visible physical infrastructure we use every day that we take for granted but can’t do without. The water reservoirs, pumps and pipelines we rely on to have a glass of water or to take a shower. The electrical plants and transmission lines that light and power our homes and businesses. The sewer systems that protect our public health. The roads and freeways that can take us anywhere in the country and deliver our food and medicine and every other item of commerce we depend on.

“But there is another infrastructure you don’t see – the invisible infrastructure of law. Without law, the physical infrastructure we take for granted would not exist as we know it. For roads or sewers to be constructed and run, contracts must be entered, funds procured by loans and bonds, and health and safety standards set by law. In fact, there is not a single thing in our lives that you care about law does not touch. Your name and identity – a matter of law. Your home and personal property – a matter of law. Same with the money in your bank account; protection from thugs and crooks; the right to speak or vote. Your citizenship and the country you live in, the United States of America, are creatures of law. Law is what ties all of us together.”

“Law as our invisible infrastructure” is my elevator pitch as to how and why law is fundamental to what we do and who we are. And just as engineers and workers attend to one kind of infrastructure, judges and lawyers attend to another.

But now I am wondering, will I still be able to give this pitch? In the infancy of the second Trump administration, we are witnessing one of the gravest internal threats to the rule of law in American history. Read more »

“Like a bird on a wire,

like a drunk in a midnight choir

I have tried, in my way, to be free. . .”

……………………….. —Leonard Cohen

The universe is synchronous,

its beauties overlap,

tunes are made of birds on wires,

Leonard sang that song for us

Nature plays its songs for us

riffs are spun of days,

melodies of suns and moons,

of particles and waves,

each to each is brought to us

All her songs belong to us

each is ours to keep,

ruthless ones of hearts on fire,

ones sublime and deep,

ones both right and wrong for us

Jim Culleny

4/27/14

Birds on a wire by Leonard Cohen

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Steve Szilagyi

June 1846 was the hottest month ever recorded in London at that time. For 22 sweltering days, temperatures soared between the 85 and 105 degrees Fahrenheit. The city’s literary luminaries—Elizabeth Barrett, Robert Browning, Alfred Lord Tennyson, and Thomas Carlyle among them—mopped their brows and grumbled about the oppressive heat like common mortals. Meanwhile, down in Piccadilly, sweating crowds lined up by the thousands outside Egyptian Hall. They had come to see P.T. Barnum’s latest sensation, the celebrated little person Tom Thumb. Barnum’s show was the talk of the town—that is, until June 22, when the heat and gossip took a backseat to shocking news. Benjamin Robert Haydon, a painter, writer, and lecturer known to them all, had been found dead in his studio, the victim of his own tragic hand.

Haydon was an extraordinary figure—brilliant, ambitious, and doomed. His life was a tale of grand aspirations, bad luck, and worse decisions. Stricken by a mysterious illness at age six, he suffered bouts of blindness for much of his life. Nonetheless, he pursued the vocation of art with fanatical zeal. Unlike many of his contemporaries who earned comfortable livings painting portraits or landscapes, Haydon devoted himself to “historical painting,” creating enormous canvases that depicted grand scenes from history and the Bible. These were not modest works; 10 by 15 feet was a typical size. But despite his herculean efforts, he rarely sold these massive paintings. The problem? They were too big to hang anywhere—and, by general consensus, they weren’t very good.

Yet Haydon’s story endures because of his remarkable personality and relentless pursuit of a hopeless dream. He inspired at least two excellent modern books: Paul O’Keeffe’s magisterial biography, A Genius for Failure, and Althea Hayter’s A Sultry Month: Scenes of London Literary Life in 1846. Haydon fascinates not because he was a great painter—he wasn’t—but because of his peculiar idealism, boundless energy, and talent for making all the wrong enemies. Read more »

by Mindy Clegg

“Well,” Lynch said, “imagine if you did find a book of riddles, and you could start unraveling them, but they were really complicated. Mysteries would become apparent and thrill you. We all find this book of riddles and it’s just what’s going on. And you can figure them out. The problem is, you figure them out inside yourself, and even if you told somebody, they wouldn’t believe you or understand it in the same way you do.” (from Variety by Chris Morris)

The director, musician, and artist David Lynch recently left us. I count myself as a fan. Twin Peaks, which aired when I was a young teen, was a revelation. Even today, few shows or films lay bare the utter weirdness and contradictions of American society in quite the same way. Lynch took the “normal” and showed its ugly face to the world. The mystery of Laura Palmer pulled everyone in, but it was the examination of small town life in America that appealed to many. His stories were full of contradictions, of how being normal can sometimes be a cover for bad intentions, while the social misfits are often the least morally compromised. As a kid who never got the knack of “fitting in” I found it easy to see these contradictions and so the elevation of the small town misfits resonated. Celebrities die all the time, and people who never met them often express sadness. We don’t know these people, but many of us feel like we do. But there are some who represent a strata of American society that often gets marginalized or stigmatized. Those deaths feel like real losses in a way that others do not. Lynch was one of those people, representing those who choose a life on the margins, despite being of the privileged class (white, middle class, etc). Lynch shared an important corrective to American exceptionalism: dark American weirdness.

Lynch offered up an important counter-narrative to the often celebratory version of Americana found in films and TV. Think of the way Steven Spielberg often invokes the imagery of small town America in his works. Lynch also loved the all-American small town, but he was drawn into the contradictions between the polite veneer and the often brutal reality. Rather than tales of typical Americans overcoming obstacles, he revealed how often aiming for that ideal and failing left people battered, bruised, even dead. In Twin Peaks Laura Palmer was a homecoming queen from a well-respected, influential, middle class family family in the pacific northwest. But her body washes up on the banks of a rushing river, wrapped in a plastic sheet. What begins as a tense “whodunit” proved to be an examination of the false veneer of small towns. The most aware and morally upright characters were not the city leaders, the “normal” men and women of Twin Peaks. Rather many of them were participating in the exploitation of teenage girls or at least ignoring that exploitation. Read more »

by Daniel Shotkin

As a senior in high school, I’ve spent four consecutive years in English classes, during which my teachers have hammered home the idea that fiction follows a set progression—Chaucer, Shakespeare, the Enlightenment, Romantics, Transcendentalism, Victorian literature, realism, existentialism, modernism, and, today, postmodernism. If each past period has been clearly defined—Romantics love the sublime, Modernists reject tradition—then the period we’re in now feels a lot less certain. Today’s stories are diverse, both in genre and style. Still, there’s one trend in modern fiction that has caught my untrained eye: a lack of creativity.

Take a look at the Oscar nominees for Best Film of 2025, and you’ll find a wide variety of stories: a black comedy about a New York stripper marrying a Russian mafia heir, a drama about a Hungarian architect emigrating to the United States, and a Bob Dylan biopic. Despite the diversity in characters, settings, stories, and genres, there’s still one aspect the Academy has failed to account for—fiction.

Of the ten nominees, only three are original works. A Complete Unknown, The Brutalist, I’m Still Here, and Nickel Boys are, for all intents and purposes, biopics. Conclave, Dune: Part Two, and Wicked are adaptations of existing works. The only fully original films recognized by the Academy are Anora, Emilia Pérez, and The Substance. While it’s not my place to dictate what happens behind the scenes of film nominations, this disregard for imaginative fiction isn’t unique to filmmaking.

Flip through an issue of The New Yorker from the past five years, and you’ll find op-eds, long-reads about niche subjects, and, almost always, a short story. Fiction has been central to The New Yorker since its inception, yet, for a magazine with such literary weight, too much of the fiction featured is, to put it mildly, dull. Read more »

by Mike Bendzela

“. . . I am one born out of due time, who has no calling here.” —Thomas Hardy

Cultural phenomena such as sports, pop/rock music, movies, television/mass media, politics, and religion/holidays have little hold on me anymore. Over time, I’ve eschewed these largely social activities. Call it adaptation; I’m not fit for them nor they for me, so seclusion has become my niche, and a fruitful one at that. Sometimes it is like I do not speak the native language — I awaken, a foreigner on my own continent, with no guide along as translator. Contemporaries will thank you for not singing along if you cannot sing in tune. This may make me culturally illiterate, but some illiterates are truly functional.

Becoming totally unsheathed from culture is to attempt the impossible: You run hard away from it, but it can run harder, having multitudes for legs. Like particulate matter in the air you breathe on your remote mountaintop, culture is ubiquitous.

Sometimes an anecdote illustrates my break with these social customs. Such episodes become signifiers and watersheds only in retrospect; at the times they occur, they seem more like puzzling anomalies or personal eccentricities. Only later do they hint towards a greater disillusionment.

Sports

This is one loss I rue a little, for I can see that fans are having fun. The noise, the team configurations, the mascots, the bands, the spectacle — all are impressive. And I can recognize the phenomenal abilities athletes have, placing them among the prodigies of our species. But the niceties of the games themselves bore me to tears, and my early associations with them were universally awful: When I went out for baseball as a kid, fly balls always thumped in the grass behind me in left field before I could even spot them. I tried out for football as a high school freshman, and the first day I heard those helmets cracking against each other I left the field and never returned, my first and last brush with physical violence. Perhaps wrestling would be more my style, less public and featuring far less velocity; but during my first match, I was so awestruck by the physique of my opponent that I ended up being pinned to the mat within sixty seconds.

Few spectators of sports actually play them, of course. My spectator experience never got much beyond high school, and one anecdote stays with me. During the last game I attended, the senior year homecoming game, our team was down by several points. We had the ball, the clock was running out. The fans in the stands were heated, hungry for a score. A play would be launched to cheers, only to finish with a crashing Awww! as our team failed to gain yards. The din was incredible. I turned to look up at the crowd in the bleachers behind me. People stood on their seats and shouted when a play started, then plopped back down, despondent. A few girls were even crying. I realized this was an emotional debacle as well as an athletic rout. A puzzling thought occurred to me at that moment of wonderment, and only years later did actual words come to me to describe what it was I was thinking:

What the hell is wrong with these people? Read more »

by Adele A. Wilby

With its pristine rainforest, complex ecosystems and rich wildlife, Ecuador has been home to one of the most biodiverse countries on Earth. For thousands of years indigenous peoples have also lived harmoniously in this rainforest on their ancestral land. All that has now changed. Since the 1960s, oil companies, gold miners, loggers and the enabling infrastructural workers have all played their part in the systematic deforestation and destruction of this complex eco-system. Human rights abuses, health issues, deleterious effects on the people’s cultures and the displacement of people have all become part of the indigenous people’s lives. But wherever and whenever oppression, exploitation and social injustice raises its ugly head, resistance will eventually emerge, and so it is with the indigenous Waorani people of the Ecuadorian rainforest, under the leadership of Nemonte Nenquimo.

With its pristine rainforest, complex ecosystems and rich wildlife, Ecuador has been home to one of the most biodiverse countries on Earth. For thousands of years indigenous peoples have also lived harmoniously in this rainforest on their ancestral land. All that has now changed. Since the 1960s, oil companies, gold miners, loggers and the enabling infrastructural workers have all played their part in the systematic deforestation and destruction of this complex eco-system. Human rights abuses, health issues, deleterious effects on the people’s cultures and the displacement of people have all become part of the indigenous people’s lives. But wherever and whenever oppression, exploitation and social injustice raises its ugly head, resistance will eventually emerge, and so it is with the indigenous Waorani people of the Ecuadorian rainforest, under the leadership of Nemonte Nenquimo.

Nenquimo’s recent autobiographical memoir, We Will Not Be Saved, is a detailed narration of her life as an indigenous Waorani woman living in the rainforest and the consequences of the extractive industrial practices on their way of life and the rainforest they live amongst. With the assistance of her husband Mitch Anderson listening, translating and rendering Nenquimo’s voice, she provides us with authentic, deep insight into the exceptional culture and world view of her people; it makes an important contribution to our knowledge of indigenous people’s lives and the devastating impact of the oil industry on those lives.

There are two parts to this book. Part One spans her childhood years in her village of Toñampare and ends with her flight from the missionary couple with whom she lived when in her teens. Nenquimo writes emotively and insightfully about those years of her life and her community’s intimate and harmonious connection to the natural environment; of her mother’s pregnancies and her twelve brothers and sisters living in a smoked filled oko; of how she makes the sweetest manioc mixture of chicha; of hunting with her father and learning to identify the footprints belonging to the diverse forms of animal life; of how she learns of the spirit that lives within the jaguar and of the power of the shamans.

The book is also significant for the way it highlights the stark contrasts between two ways of life and world views, that of the ‘cowori’, ‘outsiders’ as the white people are known in Wao Tededo, the language of the Waorani, and the life of indigenous people in the Ecuadorian rainforest. As a small child Nenquimo runs excitedly to the landing site when she hears the humming sound of an ebo, a plane, bringing the cowori, including missionaries, to her village. She could never have imagined then that one day she would find herself not running towards but running away from the Christian missionaries the plane delivered to her village. Read more »

by David J. Lobina

A specter is haunting Artificial Intelligence (AI) – the specter of the environmental costs of Machine/Deep Learning. As Neural Networks have by now become ubiquitous in modern AI applications, the gains the industry has seen in applying Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) to solve ever more complex problems come at a high price. Indeed, the quantities of computational power and data needed to train networks have increased greatly in the last 5 or so years. At the current pace of development, this may well translate into unsustainable amounts of power consumption and carbon emissions in the long run, though the actual cost is hard to gauge, with all the secrecy and the rest of it. According to one estimate, nevertheless, improving cutting-edge DNNs to reduce error rates without expert input for correction could cost US$100 billion and produce as much carbon emissions as New York City does in a month – an impossibly expensive and clearly unethical proposition.

Once upon a time, though, advances in so-called neuromorphic computing, including the commercialization of neuromorphic chips by Intel, with its Loihi 2 boards and related software, hinted at a future of ultra-low power but high-performance AI applications. These models were of some interest to me not long ago too, given that they seem to model the human brain in a closer fashion than contemporary DNNs such as Large Language Models (LLMs) can, the paradigm that dominates academia and industry so completely today.

What are these models again?

In effect, LLMs are neural networks designed to track the various correlations between inputs and outputs within the dataset they are fed during training. This is done in order to build models from which they can then generate specific strings of words given other strings of words as a prompt. Underlain by the “pattern finding” algorithms at the heart of most modern AI approaches, deep neural networks have proven to be very useful in all sort of tasks – language generation, image classification, video generation, etc. Read more »

by Alizah Holstein

A pandemic has swept the land, talk of apocalypse abounds. A charismatic political figure with a penchant for opulence and known for captivating the populace with speeches about reviving the old empire is embarking upon his second stint in power. In his crosshairs is the political establishment, and under his rule the social order shows signs of fissure.

The story rings familiar, but is it? The year is 1354. The place, Rome.

When we swoop in for a closer look, other details begin to emerge. The apocalypse as it was imagined in late medieval Italy looks different from today’s. Less water, more fire. Though maybe this is my own personal apocalypse speaking, rooted in the southern New England landscapes I know best; where I see only downpours and rising sea levels, Californians might well look into the future and envision a fireball. Four horsemen featured prominently in the medieval imagination, and alongside the extinction of mankind on earth, they would also usher in a new age, one in which justice and peace prevailed in the heavenly city, the New Jerusalem.

The political figure who wants to Make Rome Great Again is Cola di Rienzo, and if you’d lived in Europe before the twentieth century, chances are you’d have known who he was. Machiavelli praised him, and Napoleon retreated from Moscow with his story tucked in his carriage. Byron eulogized him as a radiant figure, Hitler found his charisma inspiring, and Mussolini was warned he’d end up assassinated and strung upside down by an angry mob just like Cola, and lo and behold, he did. Opera fans will recognize Cola as the revolutionary “tribune of the Roman people, “a young man clad in velvet tights whose heroic stand against the depredations of an unchecked elite class was the subject of Rienzi, Richard Wagner’s first opera to hit the charts. Late in life, the composer came to feel ashamed of his youthful score. It was too “Italian”—a descriptor Cola would have eschewed for himself in favor of the more local “Roman.” Neither adjective was revolutionary, but taking the title “tribune” really was, because no one had done it for nearly a thousand years. It recalled the ancient office of the tribune of the plebs, devised to check the power of senators and leading magistrates. Read more »

by Paul Braterman

As Heather Cox Richardson and by now many others have pointed out, a coup d’état is taking place in the United States. Even the New York Times and the Washington Post now seem aware that things are not as they should be. The coup is conducted by the Administration itself, within which Vance occupies the second highest position. This regime, like all authoritarian regimes, recognizes the power attached to the control of information, and the ability to define the conventional wisdom. For that reason, it has embarked on an energetic program of purging unwelcome information from official sources, undermining independent research, and specifying which topics may or may not even be mentioned by sources that receive any Federal funding. What follows, a piece that I began to write on the eve of the coup, should be seen in this context.

A clip posted by National Conservatism on X shows Vance quoting Richard Nixon’s saying, “The Professors are the enemy.” This sent me to the full speech from which the clip came, which Vance, at that time a candidate for election to the Senate, gave to the November 2021 National Conservatism Conference, and which has since been seen on YouTube over a hundred thousand times. I was expecting some load of easily dismissed anti-intellectual drivel. What I found, instead, was a very carefully crafted speech, with some points that do hit home, others that are subtle signals to his audience of his own conservative credentials, and, throughout, a judo-like rhetoric that reverses the moral thrust of his opponents’ arguments.

The speech begins

So much of what we want to accomplish, so much of what we want to do in this movement, in this country, I think, are fundamentally dependent on going through a set of very hostile institutions. Specifically the universities, which control the knowledge in our society, which control what we call truth and what we call falsity, that provide research that gives credibility to some of the most ridiculous ideas that exist in our country.

and concludes:

There is a season for everything in this country and I think in this movement of National Conservatism, what we need more than inspiration is, we need wisdom. And there is a wisdom in what Richard Nixon said approximately forty fifty years ago. He said, and I quote, “The Professors are the enemy.” [Applause]

What comes between deserves the closest attention, especially from those opposed to what Vance stands for. Read more »

Chandelier hanging from the ceiling of the church of Maria Weißenstein in Welschnofen, South Tyrol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Mark Harvey

Most of the “better sort” were not genuine Sons of Liberty at all, but timid sycophants, pliant instruments of despotism… —Carl Lotus Becker

It doesn’t take a lot of effort to be a bootlicker. Find a boss or someone with the personality of a petty tyrant, sidle up to them, subjugate yourself, and find something flattering to say. Tell them they’re handsome or pretty, strong or smart, and make sweet noises when they trot out their ideas. Literature and history are riddled with bootlickers: Thomas Cromwell, the advisor to Henry VIII, Polonius in Hamlet, Mr. Collins in Pride and Predjudice, and of course Uriah Heep in David Copperfield.

It doesn’t take a lot of effort to be a bootlicker. Find a boss or someone with the personality of a petty tyrant, sidle up to them, subjugate yourself, and find something flattering to say. Tell them they’re handsome or pretty, strong or smart, and make sweet noises when they trot out their ideas. Literature and history are riddled with bootlickers: Thomas Cromwell, the advisor to Henry VIII, Polonius in Hamlet, Mr. Collins in Pride and Predjudice, and of course Uriah Heep in David Copperfield.

There are some good words to describe these traits: sycophant, kiss-ass, toady, lackey, yes-man. One of my favorites is the word oleaginous, derived from oleum. It means oily and one of the best examples of this quality is the senator from the oil state, Ted Cruz. That man is oilier than the Permian Basin—oilier than thou!

There is something repulsive about lickspittles, especially when all the licking is being done for political purposes. It’s repulsive when we see it in others and it’s repulsive when we see it in ourselves It has to do with the lack of sincerity and the self-abasement required to really butter someone up. In the animal world, it’s rolling onto your back and exposing the vulnerable stomach and throat—saying I am not a threat.

There is something repulsive about lickspittles, especially when all the licking is being done for political purposes. It’s repulsive when we see it in others and it’s repulsive when we see it in ourselves It has to do with the lack of sincerity and the self-abasement required to really butter someone up. In the animal world, it’s rolling onto your back and exposing the vulnerable stomach and throat—saying I am not a threat.

We have a political class nowadays that is more subservient and submissive than the most beta dogs in a pack of golden retrievers. Most of them live in Washington DC and are Republicans. They are fully grown men and women, some in their autumnal years, still desperately yearning for a pat on the head or a chuck under the chin by President Trump. You see them crowding around him when he signs a bill, straining forward like children and batting their eyes with pick-me, pick-me smiles.

There are dozens of theories about a nation as a whole and individuals as separate beings willing to bow and scrape to an authoritarian figure. Hannah Arendt suggested that loneliness had a lot to do with it. She distinguished loneliness from solitude, the former being isolating and disempowering, the latter being a desirable state to think and reflect and meditate on things. Most of us know the paradox of feeling very lonely in certain crowds or with certain people and not lonely at all on our own in the right setting. Read more »

by TJ Price

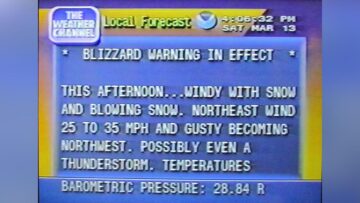

In a 2001 article in The New York Times, Elmore Leonard begins a series of ten rules for writing with “Never open a book with weather.” Whether or not Mr. Leonard is right or wrong in this dictum, I have decided to start this column with exactly that: the weather. My thoughts on such prescriptivist advice aside, nothing so moves me to awe as the aetherial forces constantly swirling both above and around us, informing the very air we breathe and sometimes literally shaping the landscape in which we live. I relish the casual conversations that others dread, in the supermarket and in passing—my forecasts often come from old codgers I happen across: My knee’s singing, they say, pensively. For sure, it’s gonna rain.

I am relatively sure I inherited this fascination from my mother, with whom I shared an avid love of The Weather Channel, back before it turned into a hopeless amalgam of advertisement and personality. It was with the intensity of sports fanatics that we tracked storms, watching the data go by as a constant cycle of shaded maps and predictions for future precipitation. In hindsight, it’s entirely possible that—due to circumstances of familial uncertainty and confusion at that time—we were attempting to do through forecasting the weather what we couldn’t do with our own lives.

The New England winter was never a question of if, it was always a question of how much, and when. Early mornings consisted of steaming instant oatmeal, orange juice, and the free jazz of The Weather Channel playing over an endless chyron of scrolling school delays and closures. Being that our town was on the farther end of the alphabet, we had to wait through all the Coventries and Middleburys and Tarringtons and Warrenvilles before we got to ours. Despite the anticipation, we were glued to the screen, speculations all based on the data: cold front is moving in quick according to the radar, and look—Tolland is closed, so is Union…

But beyond the winter, and far more exciting—perhaps because it often spun in waters so distant from ours—there was hurricane season: each mysterious, rotating devastator given a name. There was Andrew and Hugo and Bob, each grinding their inexorable way towards us, and we watched every update with anticipation, making predictions. One model said an incoming High pressure was sweeping down from the north, it would push the thing out to sea; another would say this wasn’t the case and the High was being held back by the Low coming up from the southwest—

I often find myself wondering how many people are behind these divinations, the meteorologists who cast their eyes over fluctuating numbers and patterns, their graphs filling with isobars and front lines like occult glyphs, indecipherable to the layperson. Read more »

by Mary Hrovat

When I was 17, I took an introductory course in physical geology at a community college. I was enchanted by the descriptions of the physical processes that created land forms, and also by the vocabulary: eskers and drumlins, barchan dunes, columnar basalt. I like to know how things form and what they’re called. My strongest memory of this class, though, centers on the final lecture. The professor put Earth and its landforms and minerals in a larger context. He told us about the life cycles of stars, which have produced most of the elements on Earth.

The central fact of the lecture was that the mass of a star is a key characteristic determining how long it exists and what happens as it ages. Stars are formed when gravity causes a portion of a gas cloud to collapse until its internal pressure, and thus its temperature, are high enough for nuclear fusion to begin. The energy released when, for example, two hydrogen nuclei fuse to form helium supports the mass of the star against the pull of gravity. A star’s life unfolds as a story of the equilibrium (or loss of equilibrium) between these two forces pulling inward and pushing outward. As one fuel source is depleted (for example, as hydrogen is converted to helium) other types of fusion occur in the core of the star using the new fuel source (and creating increasingly heavier elements). At the same time, hydrogen continues to fuse in a shell surrounding the core. Mature stars may have shells dominated by various elements undergoing different fusion reactions, although the available reactions depend on the mass of the star.

The professor probably described stars according to their type. I don’t remember if he mentioned the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram, although it seems likely that he would have. The HR diagram plots the luminosity of stars (the amount of light they emit) versus their temperature. When stars are plotted this way, most of them fall on a curve called the Main Sequence, which runs from hot blue stars to cool red stars along the sequence O-B-A-F-G-K-M. (In some HR diagrams, the stellar type or color is plotted on the horizontal axis as a proxy for temperature.) Stars remain on the Main Sequence as long as the gravitational and thermal forces are in equilibrium. The larger and hotter a star is, the shorter its time on the Main Sequence, because hotter stars consume their fuel more rapidly.

As they age and leave the Main Sequence, stars undergo different processes depending on their size. The universe is still too young for the very smallest stars to have exhausted their fuel, so they’re still on the Main Sequence. Stars with masses ranging from slightly less than that of the sun to 10 times the mass of the sun go through a red giant phase, ultimately undergoing core collapse and forming dense white dwarfs. Larger stars have more complicated end-of-life scenarios, typically exploding in supernovae and leaving behind superdense neutron stars or black holes. Some elements are created only in supernova explosions. Read more »