by Kyle Munkittrick

We’re on the cusp of The Culture. This Iain M. Banks series has recently replaced Star Trek as the lodestar for The Future We Want. Why? Because it shows us how good the future can be with AI. Critically, both fictions also offer key lessons about the threat and promise of human enhancement: it is coming, it could be amazing, but first it will be contentious, and if we’re not ready, we’ll suffer its worst harms and get few of its best benefits. We want The Culture and to get there, we need to take Star Trek seriously.

In his excellent essay for Arena Dean Ball asked, in essence, “Where are the clearly articulated benefits of a world with AI? Why is it worth all this risk?” The answer to Ball is, “Go read The Culture. Start with The Player of Games.” Imagining a peaceful, prosperous, and pluralistic post-scarcity utopia that is that way because it is run by benevolent ASI (called ‘Minds’) is difficult. Imagining a world where AI has so ‘solved’ biological and medical science so completely that its citizens are fundamentally post-human is even more so. The vision of The Culture is so grand and so alien that it takes a series of novels, following the daily lives of the protagonists, to begin to grasp just how incredible the future with AI could be.

In Star Trek, however, though we can reach the stars, medical technology seems not much advanced beyond that of the 20th century. It’s not due to a limitation of science, but of society. Before reaching the stars, humans endured the Eugenics Wars—a global conflict arising from first the reckless pursuit of, then catastrophic backlash to and banning of, human enhancement technologies. Think, ‘The Butlerian Jihad, but for biology.’

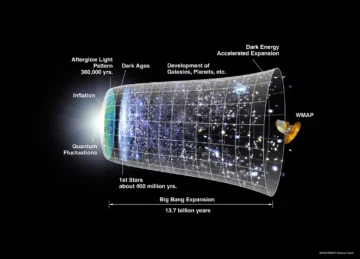

Both pieces of fiction are important because of what is very likely about to happen. In his 15,000-word manifesto Machines of Loving Grace, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei bolds one, and only one, paragraph:

“[M]y basic prediction is that AI-enabled biology and medicine will allow us to compress the progress that human biologists would have achieved over the next 50-100 years into 5-10 years. I’ll refer to this as the “compressed 21st century”: the idea that after powerful AI is developed, we will in a few years make all the progress in biology and medicine that we would have made in the whole 21st century.”

Let’s call this ~60% year-over-year acceleration of progress the “BOOM (Biological Orders of Magnitude) Decade” (2025-2035). To ‘feel the BOOM’, imagine going from discovering antibiotics (~1930) to all the medical technology we have today (IVF, MRI, GLP-1s) by 1940. People would freak out, to put it mildly. Society needs frameworks and mental models to be able to absorb and adjust to change at that speed. Just as AI alignment principles guided AI development, we urgently need enhancement alignment principles to guide the coming biological revolution. Without AI alignment, we risked creating Skynet or the Paperclip Optimizer; without enhancement alignment, we risk the Eugenics Wars—either through reckless implementation or through panicked prohibition that prevents beneficial technologies.

In preparation for the BOOM, I propose a set of principles for human enhancement technologies (HETs) as a starting point for the conversation and as fodder for consideration by both the humans and the AI who will be building these biological and medical technologies. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Reflection. Merida, Yucatan, March 14, 2025.

Sughra Raza. Reflection. Merida, Yucatan, March 14, 2025.

Everyone grieves in their own way. For me, it meant sifting through the tangible remnants of my father’s life—everything he had written or signed. I endeavored to collect every fragment of his writing, no matter profound or mundane – be it verses from the Quran or a simple grocery list. I wanted each text to be a reminder that I could revisit in future. Among this cache was the last document he ever signed: a do-not-resuscitate directive. I have often wondered how his wishes might have evolved over the course of his life—especially when he had a heart attack when I was only six years old. Had the decision rested upon us, his children, what path would we have chosen? I do not have definitive answers, but pondering on this dilemma has given me questions that I now have to revisit years later in the form of improving ethical decision making at the end-of-life scenarios. To illustrate, consider Alice, a fifty-year-old woman who had an accident and is incapacitated. The physicians need to decide whether to resuscitate her or not. Ideally there is an

Everyone grieves in their own way. For me, it meant sifting through the tangible remnants of my father’s life—everything he had written or signed. I endeavored to collect every fragment of his writing, no matter profound or mundane – be it verses from the Quran or a simple grocery list. I wanted each text to be a reminder that I could revisit in future. Among this cache was the last document he ever signed: a do-not-resuscitate directive. I have often wondered how his wishes might have evolved over the course of his life—especially when he had a heart attack when I was only six years old. Had the decision rested upon us, his children, what path would we have chosen? I do not have definitive answers, but pondering on this dilemma has given me questions that I now have to revisit years later in the form of improving ethical decision making at the end-of-life scenarios. To illustrate, consider Alice, a fifty-year-old woman who had an accident and is incapacitated. The physicians need to decide whether to resuscitate her or not. Ideally there is an

Monica Rezman. After Dark. 2023. (“this is what it’s like to live in the tropics”)

Monica Rezman. After Dark. 2023. (“this is what it’s like to live in the tropics”)