As I am writing this (September 11, 2022) the Metaculus prediction site sets arrival of AGI – aka artificial general intelligence – as early as July 25, 2029, though a more rigorous setting of the question indicates that our incipient machine overlords won’t appear until May 26, 2042.[1] As people are interested in and excited by the technology, their imaginations run ahead of their reality-testing. Alas, a significant percentage of those people also believe that, once it emerges, AGI  technology will somehow amplify itself into a superintelligence and proceed to eliminate the human race, either inadvertently – as a side effect of some other project, such as creating paper clips (a standard example), or deliberately.

technology will somehow amplify itself into a superintelligence and proceed to eliminate the human race, either inadvertently – as a side effect of some other project, such as creating paper clips (a standard example), or deliberately.

This strikes me as being wildly implausible. The history of artificial intelligence dates back to the early 1950s, when the first chess program was created and work on machine translation began and is so irregular that I don’t see how any reasonable predictions can be made.[2] The future of AI is MOSTLY UNKNOWN.

I conclude, then, that belief in AI Doom is best thought of as a millennial cult. It may not have a charismatic leader like Jim Jones of the Peoples Temple, much less be located in an isolated jungle compound. But its belief system closes it off from the world. Its vision of AI is a fantasy that is useless as a guide to the future.

AGI as Shibboleth

Artificial intelligence was ambitious from the beginning. This or that practitioner would confidently predict that before long computers could perform any mental activity that humans could. As a practical matter, however, AI systems tended to be narrowly focused. The field’s grander ambitions seemed ever in retreat. Finally, at long last, one of those grand ambitions was realized. In 1997 IBM’s Deep Blue beat world champion Gary Kasparov in chess.

But that was only chess. Humans remained ahead of computers in all other spheres and AI kept cranking out narrowly focused systems. Why? Because cognitive and perceptual competence turned out to require detailed procedures. The only way to accumulate the necessary density of detail was to focus on a narrow domain.

Meanwhile, in 1993 Verner Vinge delivered a paper, Technological Singularity, at a NASA Symposium and then published it in The Whole Earth Review.

Progress in hardware has followed an amazingly steady curve in the last few decades. Based on this trend, I believe that the creation of greater-than-human intelligence will occur during the next thirty years. (Charles Platt has pointed out that AI enthusiasts have been making claims like this for thirty years. Just so I’m not guilty of a relative-time ambiguity, let me be more specific: I’ll be surprised if this event occurs before 2005 or after 2030.)

What are the consequences of this event? When greater-than-human intelligence drives progress, that progress will be much more rapid. In fact, there seems no reason why progress itself would not involve the creation of still more intelligent entities – on a still-shorter time scale. […]

This change will be a throwing-away of all the human rules, perhaps in the blink of an eye – an exponential runaway beyond any hope of control. Developments that were thought might only happen in “a million years: (if ever) will likely happen in the next century.

That got people’s attention. The concept of the technological singularity provided a new focal point for thinking about artificial intelligence and the future. It is one thing to predict and hope for intelligent machines that will perform this that and the other task. The idea that the emergence of such machines will change the nature of history itself, top to bottom, that is a claim of a different order.

In the mid-2000s Ben Goertzel and others felt the need to rebrand AI in a way more suited to the grand possibilities that lay ahead. They settled on the term “artificial general intelligence,” aka AGI. Goertzel realized that the term had limitations. “Intelligence” is a vague idea and, whatever it means, “no real-world intelligence will ever be totally general.” Still, “it seems to be catching on reasonably well, both in the scientific community and in the futurist media. Long live AGI!”

The important point is that the term did not refer to a specific technology or set of mechanisms, as a recent debate between Steven Pinker and Scott Aaronson shows.[3] It was an aspirational term, not a technical one.

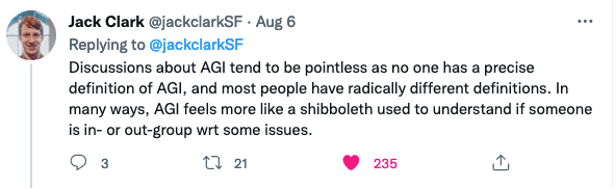

And so it remains. Thus a few weeks ago technologist named Jack Clark produced a long tweet stream about policy issues in AI. Clark was Policy Director at OpenAI for four years and is a co-founder of Anthropic, “an AI safety and research company.” In the middle of the tweet stream he observed:

If AGI has no coherent definition, then how can one predict when it will occur? It doesn’t make sense to build much of anything on the idea, much less the end of humanity.[4]

A community seems to have formed around belief in AI Doom

Destructive artificial intelligence has been a theme in popular culture for a while. The Terminator franchise is perhaps the best-known fictional depiction of destructive artificial intelligence. Before that we had Stanley Kubrick’s HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey. One might even argue that the Monsters from Id in Forbidden Planet, from 1956, is another example – in fact, I have argued that.[5] But most of the people who watch these and similar films and television programs, and read books on the same theme, these people do not believe that rogue AIs is something we have to worry about, NOW. Some of them may worry about losing their jobs to a computer, but that’s quite different from worrying about computers taking over the world and exterminating humanity.

But in 2014 Nick Bostrom published Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies (Wikipedia):

The book ranked #17 on The New York Times list of best selling science books for August 2014. In the same month, business magnate Elon Musk made headlines by agreeing with the book that artificial intelligence is potentially more dangerous than nuclear weapons. Bostrom’s work on superintelligence has also influenced Bill Gates’s concern for the existential risks facing humanity over the coming century.

That book, I conjecture, helped move fear of AI Doom from a theme in science fiction to something of concern in the halls of practical affairs. Thus in 2015 a number of and others founded OpenAI as a non-profit research company. Some of the founders, including Elon Musk and Sam Altman, were explicitly motivated out of concern over the potential threat AI posed to humanity.

Meanwhile others had been articulating these concerns at various places on the web. You will find a significant concentration of these people within an internet link or three of LessWrong, a blog and internet community that was started in 2009 by Eliezer Yudkowsky, who recently posted a list entitled AGI Ruin: A List of Lethalities – a “list of reasons why AGI will kill you”, which has attracted well over 600 comments as I am writing this. I have no idea how many people fear AI doom – thousands, tens-of-thousands, hundreds-of-thousands? I don’t know.

I do know that some of them are wealthy and are directing some of their wealth toward research on existential risk (the relevant term of art) due to rogue AI technology.[6] Thus one foundation, Open Philanthropy, has so-far given over $200 million toward mitigating “Potential Risks from Advanced AI.”[7] As I’ve not looked through the grants I don’t know how much of that is more or less specifically directed at fear of rogue AI. I’d guess that that would be a relatively small fraction of the total. Most of it appears to be targeted more generally, where rogue AI is just one thing being looked into. But it IS being investigated. Just how much money is currently chasing after rogue AI project, I do not know. My sense, though, from conversations in the Twitterverse[8] and elsewhere is that the number is rising.

Why? The threat might be real, no? Sure, that’s what these people think, and they can give detailed arguments about why the threat is real, arguments that have been developed over the last two decades or so. However, I have come to believe that AI Doom, like AGI, functions as a shibboleth, an idea that marks a group such that giving assent to it is necessary for group membership. People believe in AI Doom, not because it is justified by powerful arguments, but because they want to be a member of the club.

What about the Japanese? – The influence of culture

It is by no means obvious to me that concern about AI Doom exists wherever we find substantial communities of AI researchers. In particular, my sense – purely anecdotal – is that the Japanese do not worry about it. For what it’s worth, they’re certainly much more interested in anthropoid robots than Americans are and have spent more effort developing them.

Frederik Schodt has written a book about robots in Japan: Inside the Robot Kingdom: Japan, Mechatronics, and the Coming Robotopia (1988, and recently reissued on Kindle). He talks of how, in the early days of industrial robotics, a Shinto ceremony would be performed to welcome a new robot to the assembly line. Of course, industrial robots look nothing like humans nor do they behave like humans. They perform narrowly defined tasks with great precision, tirelessly, time after time. How did the human workers, and the Shinto priest, think of their robot compatriots? One of Schodt’s themes in that book is that the Japanese have different conceptions of robots from Westerners. Why? Is it, for example, the influence of Buddhism?

Consider Astro Boy, the best-known robot in Japanese popular culture. There are some robots that get out of control, but they never come close to threatening all of humanity. Rights and protection for robots was a recurring theme in Tezuka’s Astro Boy stories. Of course, in that imaginative world, robots couldn’t harm humans; that’s their nature. That’s the point, no? Robots are not harmful to us.

But those stories were written a while ago, though Astro Boy is still very much present in Japanese pop culture.

More recently Joi Ito has written, Why Westerners Fear Robots and the Japanese Do Not. He opens:

AS A JAPANESE, I grew up watching anime like Neon Genesis Evangelion, which depicts a future in which machines and humans merge into cyborg ecstasy. Such programs caused many of us kids to become giddy with dreams of becoming bionic superheroes. Robots have always been part of the Japanese psyche—our hero, Astro Boy, was officially entered into the legal registry as a resident of the city of Niiza, just north of Tokyo, which, as any non-Japanese can tell you, is no easy feat. Not only do we Japanese have no fear of our new robot overlords, we’re kind of looking forward to them.

It’s not that Westerners haven’t had their fair share of friendly robots like R2-D2 and Rosie, the Jetsons’ robot maid. But compared to the Japanese, the Western world is warier of robots. I think the difference has something to do with our different religious contexts, as well as historical differences with respect to industrial-scale slavery.

Later:

This fear of being overthrown by the oppressed, or somehow becoming the oppressed, has weighed heavily on the minds of those in power since the beginning of mass slavery and the slave trade. I wonder if this fear is almost uniquely Judeo-Christian and might be feeding the Western fear of robots. (While Japan had what could be called slavery, it was never at an industrial scale.)

Is Ito right? Is fear of robots, of advanced AI, a product of Western culture?

Why fear artificial intelligence?

Let me say that I really don’t know just what Silicon Valley culture has spawned a fear of the most sophisticated of its own creations. It’s one thing for Hollywood to creation films about rogue artificial intelligence. It’s something else entirely for those fictions to escape from Western culture’s imaginarium and take up residence in the hearts and minds of the people creating the technology.

Writing in Buzzfeed a couple of years ago, Ted Chiang, the science fiction writer, speculated:

I used to find it odd that these hypothetical AIs were supposed to be smart enough to solve problems that no human could, yet they were incapable of doing something most every adult has done: taking a step back and asking whether their current course of action is really a good idea. Then I realized that we are already surrounded by machines that demonstrate a complete lack of insight, we just call them corporations. Corporations don’t operate autonomously, of course, and the humans in charge of them are presumably capable of insight, but capitalism doesn’t reward them for using it. On the contrary, capitalism actively erodes this capacity in people by demanding that they replace their own judgment of what “good” means with “whatever the market decides.” […]

The fears of superintelligent AI are probably genuine on the part of the doomsayers. That doesn’t mean they reflect a real threat; what they reflect is the inability of technologists to conceive of moderation as a virtue. Billionaires like Bill Gates and Elon Musk assume that a superintelligent AI will stop at nothing to achieve its goals because that’s the attitude they adopted.

That would seem to be in the same general ballpark as Joi Ito’s speculation about slavery in the Judeo-Christian world.

I have a somewhat different thought, one that is grounded in the nature of current AI technology. For the sake of argument I am going to posit that an intellectual worker’s deepest sense of agency is grounded in the unvoiced intuitions that they have about the domain in which they work. Those intuitions lead them into the unknown, telling them what to look for, leading them to poke around here and there, guiding them in the crafting of explicit ideas and models.

I was trained in computational semantics in the “classical” era of symbolic computing. I read widely in the literature and worked on semantic network models. I have intuitions about the structure of natural language semantics. Others worked on syntax or machine vision.

Deep learning is very different. In deep learning you create an engine that computes over huge volumes of data to create a model of the structure existing in individual items, whether texts or images. This leads to intuitions about how these ‘learning’ engines work. But those intuitions DO NOTE translate into intuitions about the domain over which a given engine works.

Thus the deep learning researcher’s intuitions are isolated from the mechanisms that are actually operating in the object domain. Those mechanisms are opaque. They cannot have a sense of agency about those mechanisms for they did not design and fabricate them.

There is a peculiar sense, then, in which deep learning technology is already out of control. It is a bit like magic. If we can’t control it, then surely it will turn on us.

This suggestion is not in direct contradiction to the more political and ideological proposals offered by Ito and Chiang. Rather they would seem to be complementary. Beyond this I simply note that the world is changing in profound ways. Belief in Doomsday AI can give us little or no insight into those changes. It will not help us to meet the real challenges posed by AI.

Here be dragons.

[1] Here’s the URL for the less stringent Metaculus version of the question: https://www.metaculus.com/questions/3479/date-weakly-general-ai-system-is-devised/. Here’s the URL for the more stringent version of the question: https://www.metaculus.com/questions/5121/date-of-general-ai/.

[2] For a recent version of a long-standing argument against the possibility of artificial intelligence, see Ragnar Fjelland, Why general artificial intelligence will not be realized, Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, 7, 10, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0494-4. Rodney Brooks has been offering fairly explicit predictions about advances in robotics and AI that are, on the whole, skeptical. See his most recent Predictions Scorecard, 2022 January 01, Robots, AI, and other stuff, https://rodneybrooks.com/predictions-scorecard-2022-january-01/.

[3] The debate took place at Scott Aaronson’s blog, Shtetl Optimized, in two stages. The first stage had posts by both Pinker and Aaronson followed by 302 responses: Steven Pinker and I Debate AI Scaling, June 27, https://scottaaronson.blog/?p=6524. The second stage again had posts by both Pinker and Aaronson, this time followed by 283 responses: More AI debate between me and Steven Pinker!, July 21, 2022, https://scottaaronson.blog/?p=6593. For what it’s worth, I commented in both stages.

[4] If you want an explicit argument against the possibility of AI apocalypse, Robin Hanson – who is something of a fellow traveler to these zealous prophets of doom – has provided one, Why Not Wait On AI Risk? Overcoming Bias, June 23, 2022, https://www.overcomingbias.com/2022/06/why-not-wait-on-ai-risk.html.

[5] William Benzon, From “Forbidden Planet” to “The Terminator”: 1950s Techno-utopia and the Dystopian Future, 3 Quarks Daily, July 19, 2021, https://3quarksdaily.com/3quarksdaily/2021/07/from-forbidden-planet-to-the-terminator-1950s-techno-utopia-and-the-dystopian-future.html.

[6] See the “Mitigation” section of the article, Existential risk from artificial general intelligence, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Existential_risk_from_artificial_general_intelligence#Mitigation.

[7] See the page, Artificial Intelligence, at Open Philanthropy, August 19, 2022, https://www.openphilanthropy.org/focus/potential-risks-advanced-ai/.

[8] For example see this tweet by Timnit Gebru from May 29, 2022, https://twitter.com/timnitGebru/status/1531107974642647041?s=20&t=YUadMIcvZEbNQQHQlzaKFg.