by Gus Mitchell

This September marks 50 years since the deaths of three men. One died at the very beginning of the month, in Oxford, one in the middle, in Santiago, and one at the end, in Vienna.

Anyone likely to be reading this will have heard of J.R.R. Tolkien, who died on 2 September in Oxford, city of his life and work, aged 81. Unfortunately the contemporary world has absorbed Tolkien to an unhealthy extent that sweetens and ultimately sickens his achievement. His achievement was to create myth anew. I use that word order deliberately, as opposed to “created a new mythology”.

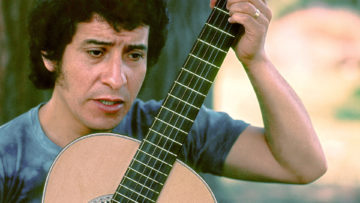

I don’t know how many people will have heard of Victor Jara. If they haven’t, they ought immediately to stop reading until they have given their full attention to “Manifiesto”, one of the really incomparable things ever committed to record. “Manifiesto” was recorded in August 1973. It was released posthumously; in its closing lines, Jara had written: “For a song has meaning / When it beats in the veins / Of a man who will die singing / Truthfully singing his songs.” And Jara was murdered the following month, on September 16th, doing what he himself had predicted.

Many people will have heard of W.H. Auden. Another acronymous luminary of 20th century British letters, he is also its greatest poet. Auden died on 29 September in Vienna, aged 66: rather lonely, estranged from his partner Chester Kallman, intending himself to make his way back to Oxford, and having likely swallowed his habitual nightly dose of barbiturate and vodka (his practice for three decades.) Auden was the kind of poet that doesn’t really exist anymore: a grand reflection of his age.

September also marks fifty years since the Pinochet coup in Chile, a coup supported by both the United States and the United Kingdom, and that would lead first to the deaths of the democratically elected socialist president Salvador Allende, then at least two thousand more Chileans, and the torture and imprisonment of more than thirty thousand more. On the 12 September 1973, the morning after the coup and Allende’s suicide, Victor Jara, along with five thousand others were arrested by the fascists and taken as prisoners to the Estadio Chile in Santiago.

Jara defined himself as “a music worker, not an artist. People and time will decide [the latter].” Jara was born in 1932, raised among the rural poor and peasants, and after moving to Santiago, studying and directing theatre, grew frustrated with the limited reach of all but song––specifically the folk music of the New Chilean Song movement, led by its founder and his mentor Violeta Parra––to reach the lives of working people. Jara devoted himself more and more to song and became the essential leader of the movement. Following Parra’s example, he toured the country singing for and about the local and working people, in constant support of Allende’s Popular Unity party. Many of Jara’s songs reinforce that defending people and defending land––both, of course, to be devastated by the fascists––is inseparable. He sang “for the people who labour / so that the future may flower” and so for Chile itself: “a far strip of country / narrow but endlessly deep.” His voice is at once gentle and strong, a lilting tenor driven by urgency.

Auden was probably the last poet of his kind. That age being the modern one, and Auden a repentant modernist, he was constantly and ironically and self-aware of the fact that––as he most famously stated the case––“poetry makes nothing happen”; yet he wrote as though it did, as though the truth which the poem struggled to accomplish were a deeply consequential matter, with implications for English itself––“mother tongue”, as he was fond of calling it. He was probably the last poet, too, to have a voice that people counted on, that was listened for and personal to people who might not ordinarily have kept up with the poetry.

Auden tried to say and reconcile important things: literature, faith, history, science, politics, society, war, psychology, freedom, responsibility, and (the agent binding all the rest) morality and ethics, a search for the Good. He was fond of abstract, grand capitalisations, and in his poetry, at least, they might still be locatable in the modern age. His poetic and prose voice were––although he was rightly suspicious of his own gift––effortlessly authoritative, and it was an authority that no public figure, poet or intellectual, could approach now.

Whether Middle Earth will persist in our imaginary for another hundred or thousand years will determine J.R.R. Tolkien’s success in creating, as his commentators have often dubbed it, “a new mythology”. What Tolkien did do was to create myth anew: he showed the modern world that it was no different from any other human epoch in its need for the mythic dimension. We now call this “High Fantasy” or just “fantasy literature”, but that is just the inevitable hollowing that occurs in most generations following a significant cultural discovery, when the originating genius vacates, and imitation and codification takes over. Today, we can barely recognise Tolkien’s achievement for what it really was, since for most of the culture, now, Middle Earth is yet another brand. It was probably only possible for this to be the work a man who had himself experienced and survived the shattering of all previous reality represented by the slaughter of the First World War. It’s often called “the first machine war”. But what this really, ultimately means is that it was the first algorithmic war; the first war fought under, and conducted according to, the imperatives of an emerging global diktat of capital, the same one that, in 1973, would depose Salvador Allende.

As Victor Jara waited (as, probably, he knew) to die in the stadium, he was writing a poem––a poem commonly known today as “Estadio Chile.” It was apparently composed on his second night there and committed to various memories and scraps of paper even in the moment, and it would be smuggled out to Jara’s widow, Joan (still living, at 97) in a shoe, and spread underground. It was, like “Manifiesto”, a posthumous manifesto to an imprisoned people. His fellow prisoners attested to Jara’s example in the stadium itself: encouraging, singing for those around him, popular songs, and snatches of the poem-in-progress. That was before he was separated from the crowd by militia, his nails torn off, his hands broken, ordered to play the guitar, brutally beaten, before finally––apparently still singing––being shot in the head and then a further 43 times.

If a poem, among many other things, is an attempt to suspend time and capture a moment or a state of true experience or understanding, then “Estadio Chile” must be one of the most preciously true poems of the 20th century. Here is a translation of that poem, which deserves nothing less than quotation in full:

There are five thousand of us here in this small part of the city

We are five thousand

I wonder how many we are in all the cities and in the whole country?

Here alone are ten thousand hands which plant seeds and make the factories run

How much humanity exposed to hunger, cold, panic, pain, moral pressure, terror, and insanity?

Six of us were lost as if into starry space

One dead, another beaten as I could never have believed a human being could be beaten

The other four wanted to end their terror––one jumping into nothingness, another beating his head against a wall, but all with the fixed stare of death

What horror the face of fascism creates!

They carry out their plans with knife-like precision

Nothing matters to them

To them, blood equals medals, slaughter is an act of heroism

Oh God, is this the world that you created, for this your seven days of wonder and work?

Within these four walls, only a number exists which does not progress, which slowly will wish more and more for death

But suddenly my conscience awakes and I see that this tide has no heartbeat, only the pulse of machines and the military showing their midwives’ faces full of sweetness

Let Mexico, Cuba and the world cry out against this atrocity!

We are ten thousand hands which can produce nothing

How many of us in the whole country?

The blood of our President, our compañero, will strike with more strength than bombs and machine guns!

So will our fist strike again!

How hard it is to sing when I must sing of horror

Horror which I am living, horror which I am dying

To see myself among so much and so many moments of infinity

In which silence and screams are the end of my song

What I see, I have never seen

What I have felt and what I feel will give birth to the moment…

It is unclear, of course, whether Jara finished the poem, but it seems unanswerably right that it ends with an unresolved embrace, with faith in the future which its author would never see––but which an echoing demonstration of Good might, somehow, help to bring about. And that is heroism, if anything is.

In a lecture, “The Hero in Modern Poetry”, delivered in 1954, Auden described the problem of locating heroism within modern literature. What Auden rather vaguely terms “the coming of the machine” –– by which I think he means not merely mechanised war but the Machine Age, the whole technologised 20th century––has absorbed all previous “sources of authority. The moment you get a technological civilisation, there is at once a divorce of power from excellence…wars are won, in the end, by machines, which take no oath of loyalty.” Among the technological, modernised, bureaucratic nations, whether capitalist or communist, it is “as impossible to praise public figures as to blame––their power depends much less on will than on the machines they command.” Again, as in the case of the First World War, we should conceive the term “machine” to have wide (more than literal) application. For Auden, it is the Unknown Soldier, that anonymous symbol of sacrifice to the machine, who is “the only kind of a hero possible in a technological civilisation––and art cannot touch it.”

What really made The Lord of the Rings was Tolkien’s reintroduction (made possible by a modern academic’s expertise in European philology and mythology) to reintroduce Romance and Epic tradition into a European literature which had long bad farewell to those genres and replaced them with the interiorities of the novel––the new form of an increasingly self-aware market. Romance and epic describe the deeds of heroes, and wherever there is a myth (which always acknowledges divinity of various orders) then you will also find heroic powers, containing some part of the divine but, fatally, of a lower order than the gods. Thus, Achilles; thus, Gilgamesh, a “two thirds divine and one third mortal” warrior king, who is also terrified of death; thus Aragorn, the prophesied future unifier of Middle Earth, yet also “mortal man, doomed to die.” And the hobbits, of course, the commonest of heroes, those heroes of the commons. Yet Tolkien, as Auden said, was also of the age that could neither commit nor admit heroism.

Tolkien and Auden’s odd, uncertain friendship began at Oxford in the 1920s, when Auden, who was studying English and was fascinated with Old and Medieval English and the Norse Sagas attended many of Tolkien’s lectures. According to Auden, it was hearing the Professor read electrifyingly from Beowulf rather than his lectures (“I do not remember a word he said”) which made the impression. Auden later proved Tolkien’s most important critical champion amongst modernist high brows, and it was probably his partial initiation by Tolkien into the reasons and mysteries of language itself which earned Tolkien Auden’s undying loyalty.

Tolkien’s building blocks, his main motivators in creating what Auden dubbed his “Secondary World”, one in which heroes could again exist, were the words of old or “dead” languages he loved so well. As Tolkien himself put it, words themselves “are custodians of ancient cultures and thus infuse the present with the past.”

Or as Auden wrote in his old age: “Though I suspect the term is crap / If there is a Generation Gap, / Who is to blame? Those, old or young / Who will not learn their Mother-Tongue.” Language, like the earth, air, sky, water which is the property (and, Auden indicates, the responsibility) of everyone and no-one.

Tolkien once described the meaning in his great books: “they are, like most great stories, at root and behind veils of myth and metaphor, about particular people on a certain patch of soil they call home, both of which are worth defending against those who wish them harm.” (The other time he offered so pithy a definition of his intentions was in a brilliant BBC documentary in 1968. The Lord of the Rings, he replies, is about what “all great stories are about: death. The inevitability of death.”)

Jara sang in “Manifiesto”, his last song:

I sing because the guitar

has purpose and reason

it has a heart made of earth

and wings like a dove

A song makes sense

when it flows through the veins

of he who will die singing

the real truths

In the place where everything goes

and where everything begins

a song that has been brave

will always be a new song

The humanity of a hero is in their reflection of our universal double nature: capable of divine transformation on earth (if our myths, too, are always about any one thing, it is change, as Ovid understood) because of their fidelity to their own mortality.

Instead of a conclusion, three poems.

In western lands beneath the Sun

the flowers may rise in Spring,

the trees may bud, the waters run,

the merry finches sing.

Or there maybe ’tis cloudless night

and swaying beeches bear

the Elven-stars as jewels white

amid their branching hair.

Though here at journey’s end I lie

in darkness buried deep,

beyond all towers strong and high,

beyond all mountains steep,

above all shadows rides the Sun

and Stars for ever dwell:

I will not say the Day is done,

nor bid the Stars farewell.

J.R.R Tolkien

He was found by the Bureau of Statistics to be

One against whom there was no official complaint,

And all the reports on his conduct agree

That, in the modern sense of an old-fashioned word, he was a saint,

For in everything he did he served the Greater Community.

Except for the War till the day he retired

He worked in a factory and never got fired,

But satisfied his employers, Fudge Motors Inc.

Yet he wasn’t a scab or odd in his views,

For his Union reports that he paid his dues,

(Our report on his Union shows it was sound)

And our Social Psychology workers found

That he was popular with his mates and liked a drink.

The Press are convinced that he bought a paper every day

And that his reactions to advertisements were normal in every way.

Policies taken out in his name prove that he was fully insured,

And his Health-card shows he was once in hospital but left it cured.

Both Producers Research and High-Grade Living declare

He was fully sensible to the advantages of the Instalment Plan

And had everything necessary to the Modern Man,

A phonograph, a radio, a car and a frigidaire.

Our researchers into Public Opinion are content

That he held the proper opinions for the time of year;

When there was peace, he was for peace: when there was war, he went.

He was married and added five children to the population,

Which our Eugenist says was the right number for a parent of his generation.

And our teachers report that he never interfered with their education.

Was he free? Was he happy? The question is absurd:

Had anything been wrong, we should certainly have heard.

W.H. Auden

Victor Jara of Chile

Lived like a shooting star

He fought for the people of Chile

With his songs and his guitar

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

Victor Jara was a peasant

He worked from a few years old

He sat upon his father’s plow

And watched the earth unfold

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

Now when the neighbors had a wedding

Or one of their children died

His mother sang all night for them

With Victor by her side

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

He grew up to be a fighter

Against the people’s wrongs

He listened to their grief and joy

And turned them into songs

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

He sang about the copper miners

And those who worked the land

He sang about the factory workers

And they knew he was their man

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

He campaigned for Allende

Working night and day

He sang “Take hold of your brothers hand

You know the future begins today”

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

Then the generals seized Chile

They arrested Victor then

They caged him in a stadium

With five-thousand frightened men

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

Victor stood in the stadium

His voice was brave and strong

And he sang for his fellow prisoners

Till the guards cut short his song

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

They broke the bones in both his hands

They beat him on the head

They tore him with electric shocks

And then they shot him dead

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

Now the Generals they rule Chile

And the British have their thanks

For they rule with Hawker Hunters

And they rule with Chieftain tanks

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

Victor Jara of Chile

Lived like a shooting star

He fought for the people of Chile

With his songs and his guitar

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

Adrian Mitchell