by Richard Farr

This is the first part of a two-part essay.

I got into political philosophy out of sheer puzzlement. Surely we ought to know how to run human communities by now? But political ideologies were like religions: everyone thought they knew what was true and everyone thought that everyone who disagreed with them was either evil or a fool. How did we find ourselves in this swamp of struggle and contradiction? Plato had got the enterprise of political philosophy off to a clean enough start, hadn’t he, all those centuries ago? Why so little agreement about absolutely anything?

Let’s spend a moment with Plato, and let’s leave aside for now the worry that creeps like a sickness over every reader of the Republic at some point: given the Grand Guignol absurdity of its conclusions, what if the whole thing is actually a joke that we in our earnestness keep failing to get? What if we’re not reading a defense of the most extreme rationalist authoritarianism imaginable, but a parody of such a defense? And what if the joke is on Plato’s fellow philosophers especially, we being the ones most likely to find the central idea flattering?

Taken instead at the usual face value, Plato says that everything will be hunky-dory in human affairs if only the right authorities are in authority. Mr. P. is not thinking of people with a college degree, or wonks with a loud presence on social. His much grander fantasy is for us to be ruled by a class of men and women who have created, perfected and mastered The Science of Human Flourishing. They will be bureaucrats of wisdom. They will know how life itself works; they will therefore be able to safely pilot (and will be motivated exclusively by the desire to safely pilot) this magnificent but temperamental vessel called the State.

Some note a chicken and egg problem here. If these ‘philosopher kings’ can emerge only from decades of training in the right ethikē, or moral character, but the only way to provide such an education is to bring them up in an appropriately run polis, and if the only people who could ever create such a polis are this very same group of olive-munching übermenschen, then, um … but let’s leave that aside too. The idea of a state run on rational principles, by rational people, is a good place to start. So we lesser philosophers should be able to work out the details, no?

Yet when I first stumbled into Political Ideas 101, a hundred generations later, what I found was neither a refinement of his solution nor convergence on an alternative, but a shrieking monkey cage of chaos. Right, left and center, wherever I looked there were clever and well-informed people beating their chests with their fists, spitting as they raised their voices, zealously committed to views about who should be in charge, and why, that were radically at odds with the views of the people sitting across from them.

Only in books did I encounter Divine Right monarchists, White-Man’s-Burden empire-builders, or the pitiless do-goodery of Plato’s own imaginary Central Committee. But in my neck of the woods — the late twentieth century — there were real live liberals of many colors, theocrats in many different vestments, starchy tradition-is-everything conservatives, milquetoast Fabian socialists, engine-of-history Marxists, bureaucratic Euro-Marxists, man-the-barricades Leninists, man-the-other-barricades-Trotskyists (and Maoists and Spartacists), little-England or little-Wherever nativists, techno-utopians, Hayek-via-Rand libertarians, Quaker pacifists, Chomskian democratic socialists, non-Chomskian social democrats, neo-conservative worship-the-market plutocrats, neo-liberal worship-the-market plutophiles, Third Way communitarians, anarchists, anarcho-syndicalists, leftist liberation Catholics, bioregionalists, and rope-sandaled back-to-subsistence eco-communards.

To name a few.

In one way it was a delight to encounter this variety, especially if like me you were depressed beyond measure by the ruling chicken-or-beef of American party politics — This swamp of corruption, as Engels nailed it long ago, in which two great gangs of political speculators… alternately take possession of the state power… who are ostensibly its servants, but in reality exploit and plunder it.

But the tenor and quality of the multivocal debate seemed discouraging in its own special way. Pluck any advocate at random from the roaring crowd; as likely as not you’d find someone certain about their own solutions, full of contempt for the errors in the competing solutions, and blind to the fact that their own weakest arguments always came when building the positive program.

Anarchist writers such as Proudhon and Bakunin had (it seemed to me) sharp, precise and ultimately devastating criticisms of revolutionary socialism, which the socialists sneered at, misinterpreted or ignored — especially when the conversation turned to all the worst things that had been done some tens of millions of times over in order to clear the way for the Future. (As François de Charette alas failed to say, it’s amazing how many eggs you can break without managing to produce anything resembling an omelette.) On the other hand those revolutionary socialists, reliably painted as fanatics and dreamers by those whose interests were furthered by such calumny, showed their intellectual mettle by slicing up liberals like pastrami. The liberals in their turn had telling objections to key conservative ideas. Meanwhile the conservatives, who were especially strong on the dangers inherent in the very idea of a political program, and were therefore quite effective critics of everyone else tout court, made absolute nonsense of the naïveté of the anarchists.

Taken together like this, the available political ideologies seemed to form a self-guzzling intellectual Oroborus — and any pair of opponents suggested the more domestic picture of two decapitated butlers, each still walking stiffly about the drawing room while carrying, on a tastefully plain silver platter of the kind Paul Revere might have made, the other’s head.

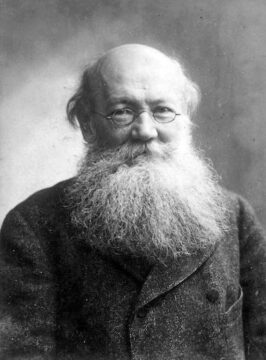

I developed my own prejudices of course, favoring some ideologies more than others. I favored anarchism partly because I fell in love with Peter Kropotkin — I mean, have you ever seen a nicer, saner face? A Russian prince, he becomes a Court Page to Alexander II, gives it all up because he passionately hates serfdom, and roams the Russian Arctic for years — covering tens of thousands of miles in brutal conditions — because he passionately loves nature. Gentle, principled, brilliant and intense, he is a diligent student of Darwin but returns from his travels with acres of notes and a highly original observation. The architecture of survival is not ruthless competition between individuals. It’s families and groups and whole species engaging in “mutual aid.”

Another reason I liked the anarchists was their thrillingly keen sense of smell on the subject of Platonic and other self-appointed experts. Kropotkin was onto it — it was why he came to despise the Bolsheviks — but perhaps Bakunin said it best:

The principal vice of the average specialist is his inclination to exaggerate his own knowledge and deprecate everyone else’s. Give him control and he will become an insufferable tyrant. To be the slave of pedants – what a destiny for humanity! Give them full power and they will begin by performing on human beings the same experiments that the scientists are now performing on rabbits and dogs.

There was a third thing too. Certain -isms are easy to denounce and dismiss after a glancing look at the history books: Communism, Fascism. But even they did not seem to spark quite the same febrile pearl-clutching hysteria as Anarchism. Why did we keep being taught that the one political ideology rooted in the idea of nurturing and protecting our instinct to care for one another was uniquely awful, uniquely synonymous with mindless chaos and violence? Or to put it as an anarchist might: what mechanisms were at work in creating this picture, what interests were being served by maintaining it — and how might we help each other recognize and escape from them?

*

At a café in Mexico City, a local man is telling me about the earthquake of September 1985.

“The epicenter was hundreds of miles away, off the Pacific coast. But it was a strong quake and many of these neighborhoods are built on what was once Lake Texcoco. The soil liquefied. Hundreds of buildings collapsed. Five thousand people died.”

In his account of the aftermath, he describes the official response as hopelessly inadequate. “These streets were filled with rubble and bodies,” he says. “Nobody showed up from the government. It was anarchy. Anarchy!”

For about two seconds I completely misunderstand what he means.

“No structure, no rules, no instructions from above. Everyone wanted to help, so everyone helped. And it worked.” He shook his head and repeated the word with a look of wonder and affection on his face. “Anarchy!”

Perhaps he was engaged in rose-tinted hindsight, but what he said resonated with me because I’d just read a powerful little book by the late great James C. Scott, Two Cheers for Anarchism. Here was someone else willing to countenance the idea that “anarchy” might be synonymous not with a brutal Hobbesian all-against-all but with natural, effective, beautifully spontaneous cooperation.

Scott was not an anarchist, and he offers no general doctrine of how political authority might atrophy, evaporate, or be abolished. Instead he gives us a rich, readable, often funny feast of insights into all our political thinking (and not-thinking) about the role of authority in our lives, all derived from what he calls his attempt to look at politics with “a sort of anarchist squint.”

I’ll say more about Scott’s anarchist squint next month. I predict with some confidence that Plato — the arch anti-anarchist, if we are to take him at his word — will show up.

*

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.