by Alizah Holstein

Think of a Roman monument. What leaps to mind? The Pantheon? The Colosseum? The Arch of Constantine? Maybe even the aqueducts? I’ll wager that when you thought of the word “monuments,” your imagination traveled upwards instead of down. For what is a monument if not a tall, grand thing, large, and to some perhaps, looming? I do recognize it’s possible—though unlikely—that you conjured the catacombs. And it’s even less likely that you thought of roads.

Cultural critic Robert Hughes described roads as Rome’s greatest physical monuments. Their network extended some 50-75,000 miles and they were the sine qua non of Rome’s expansion. I should add a minor but nonetheless relevant detail here: some of my happiest moments have been spent on Roman roads. As were some of yours, in all likelihood, if you have ever felt ebullient in Rome or on the Italian peninsula, or indeed in Spain or France or England or Germany or the Balkans or Greece or Turkey or Syria or Israel or Gaza or Egypt or Algeria or Morocco.

Let me put another question to you. What is your favorite Roman road? If you’re a pilgrim, you might say the Via Francigena. And should you offer the Via Flaminia, Via Aurelia, or Via Aemilia or some other ancient equivalent, I imagine you have your reasons. But if you are a romantic like me, the only possible answer is the Via Appia, which is, after all, the regina viarum, the queen of roads. Think of cypress trees, ancient, crumbling tombs, jasmine and pinecones and fields of wildflowers. Think also of tourist traps, gladiator impersonators, a War World II massacre site, and prostitution. Think of paradox as the defining feature of the human condition. Still, even its name is beautiful: Via Appia. Look at all those a’s and i’s, like a palindrome just off its center, the V and A the very valleys and arêtes through which the road cuts. Read more »

Sughra Raza. The Visitor. Mexico, March 2025.

Sughra Raza. The Visitor. Mexico, March 2025.

At a Christmas market in Germany, I told my German girlfriend’s mother that I masturbate with my family every December.

At a Christmas market in Germany, I told my German girlfriend’s mother that I masturbate with my family every December. The File on H is a novel written in 1981 by the Albanian author Ismail Kadare. When a reader finishes the Vintage Classics edition, they turn the page to find a “Translator’s Note” mentioning a five-minute meeting between Kadare and Albert Lord, the researcher and scholar responsible, along with Milman Parry, for settling “The Homeric Question” and proving that The Iliad and The Odyssey are oral poems rather than textual creations. As The File on H retells a fictionalized version of Parry and Lord’s trips to the Balkans to record oral poets in the 1930’s, this meeting from 1979 is characterized as the genesis of the novel, the spark of inspiration that led Kadare to reimagine their journey, replacing primarily Serbo-Croatian singing poets in Yugoslavia with Albanian bards in the mountains of Albania.

The File on H is a novel written in 1981 by the Albanian author Ismail Kadare. When a reader finishes the Vintage Classics edition, they turn the page to find a “Translator’s Note” mentioning a five-minute meeting between Kadare and Albert Lord, the researcher and scholar responsible, along with Milman Parry, for settling “The Homeric Question” and proving that The Iliad and The Odyssey are oral poems rather than textual creations. As The File on H retells a fictionalized version of Parry and Lord’s trips to the Balkans to record oral poets in the 1930’s, this meeting from 1979 is characterized as the genesis of the novel, the spark of inspiration that led Kadare to reimagine their journey, replacing primarily Serbo-Croatian singing poets in Yugoslavia with Albanian bards in the mountains of Albania.

The Paradise, Pandora and Panama Papers, exposing secret offshore accounts in global tax havens, will be familiar to many. They are central to the work of economic sociology professor, Brooke Harrington. She has spent many years researching the ultra-wealthy and several books on the subject have been the result. Her latest book Offshore: Stealth Wealth and the New Colonialism is a continuation of her research; it focuses on ‘the system’, the professional enablers who support and advise the ultra-wealthy and make it possible for them to store and conceal their phenomenal fortunes in secret offshore accounts.

The Paradise, Pandora and Panama Papers, exposing secret offshore accounts in global tax havens, will be familiar to many. They are central to the work of economic sociology professor, Brooke Harrington. She has spent many years researching the ultra-wealthy and several books on the subject have been the result. Her latest book Offshore: Stealth Wealth and the New Colonialism is a continuation of her research; it focuses on ‘the system’, the professional enablers who support and advise the ultra-wealthy and make it possible for them to store and conceal their phenomenal fortunes in secret offshore accounts.

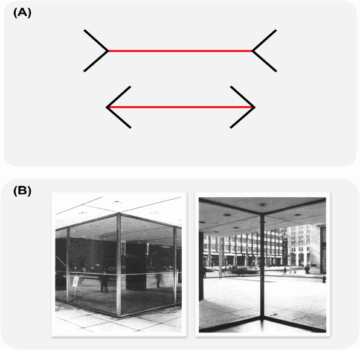

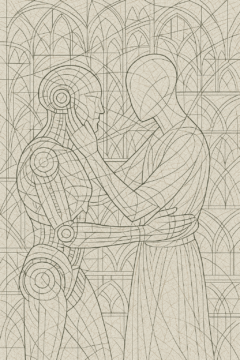

Sughra Raza. Light Tricks, Seattle, March, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Light Tricks, Seattle, March, 2022.